More than 58.5 million citizens uploaded their selfies with the national flag on or around August 15. So says the Union ministry of culture, having gleaned the data from the Har Ghar Tiranga website. The initiative sought to have 200 million households raise the Tricolour between August 13-15 as part of the celebrations of India completing its 75th year of Independence. The goal may not have been met fully but the government would like to believe that the campaign was a phenomenal success. Nitpicking over these numbers is unwarranted. The public enthusiasm was discernible; moreover, the powers that be had pulled out all the stops to turn the event into a spectacle — with the usual winks and nudges. A circular from the ministry of corporate affairs permitted companies to spend their CSR funds on activities related to the Har Ghar Tiranga campaign. There was the usual stick-wagging too: the chief of the Bharatiya Janata Party in Uttarakhand, Mahendra Bhatt, directed party workers to send him photographs of homes that did not display the Tricolour so that the proverbial chaff of “anti-nationals” could be separated from the wheat of “nationalists”.

Mr Bhatt and his ilk would perhaps be surprised — indignant? — to learn that many Indians — sons and daughters of soil, their steely frames cast from the fire of patriotism — had not hoisted the national flag even on August 15, 1947. This is because on that day some of them were giving a far fiercer test of their love for the motherland. Mallu Swarajyam — she died earlier this year — was one such patriotic Indian. On India’s first Independence Day, in what is now Telangana, Mallu and her fellow revolutionaries — PARI’s Instagram handle documented her recently — were battling the Nizam’s private militia and police with the help of slingshots and rifles.

The national flag had stayed down in parts of Malda, Murshidabad and Nadia on that auspicious day as well. The (dis)credit for that should go to Sir Cyril John Radcliffe, the joint commissioner of the boundary commissions for Bengal and Punjab, who had the unenviable task of dividing an entire subcontinent in a race against time. The result, apart from an unprecedented human tragedy, was a clutch of errors whose price was paid by the people of Malda, Murshidabad and Nadia, among other places. For three whole days, neighbourhoods in these three districts remained petrified with anxiety after hearing that their lands would go to Pakistan. Finally, Radcliffe’s ‘miscommunication’ was rectified with the reassuring announcement that Malda, Murshidabad and Nadia would remain with India. Even today, residents in these parts celebrate another Independence Day on August 18.

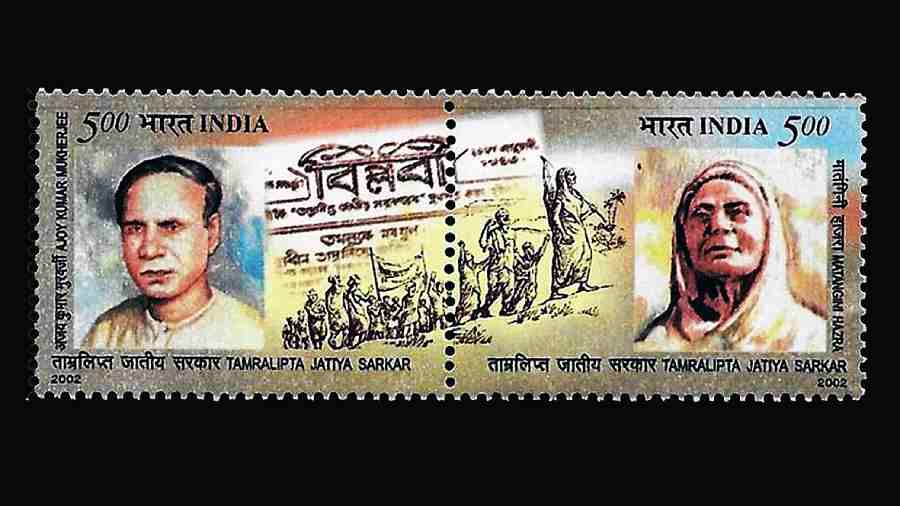

Contai and Tamluk in East Midnapore salute the national flag following a different timeline as well. This can be attributed to their energetic participation in a fight for liberation, something that cannot be claimed by the ideological minder of India’s ruling regime. The Tamralipta Jatiya Sarkar encompassing two subdivisions — this was one of the instances of a parallel, people’s government functioning independently during British raj, that too for two whole years — came to life on December 17, 1942. Spearheaded by Satish Chandra Samanta, this astounding entity, helmed by, among others, Ajoy Mukherjee, Sushil Kumar Dhara and Bengal’s ‘Gandhi buri’, Matangini Hazra, had its own armed wing, looked after law and order, and undertook relief work such as cyclone rehabilitation. It bowed — finally — in 1944, not to the British but to M.K. Gandhi’s instruction. East Midnapore still marks a second, albeit original, Independence Day on December 17.

A gifted scholar or researcher may be able to ferret out more interesting nuggets about such liberated corners of India that included, apart from the indigenous administration of Midnapore, the people’s governments of Balia (Uttar Pradesh), Satara (Maharashtra), Talcher (Odisha) and North Bhagalpur (Bihar). What these places and their people expose is the futility of imagining the trajectory of India’s freedom struggle as cohesive and linear. It wasn’t. The nature of Indian nationalism was peculiarly diverse, characterised by tides high and low, an ocean force fed by individual currents each of which merit closer examination. Such a scrutiny is necessary as it could help assess whether the discourse on and, indeed, knowledge of the nationalist enterprise is representative in nature.

The need for such an interrogation has been echoed by a recent, engaging book — Pramod Kapoor’s 1946: Last War of Independence — which studied the mutiny in the Royal Navy, yet another crucial chapter that has been reduced to an afterthought in the reproductions of the anti-colonial movement. Kapoor wonders, quite correctly, why “(i)nstead of being enshrined in public memory alongside the Salt March, Jallianwala Bagh, etc, the naval mutiny of 1946 tends to get relegated to just a footnote…”

The allegation of the curation of even — the result of the hierarchies of ideology, class, caste and gender — leads to an audacious, but pulsating, hypothesis: did the undoubted political success of Gandhian ahimsa and pacifism and their subsequent domination of the epistemology of India’s march to liberation leave little or no space for an objective analysis of those who believed in alternative — armed — movements to achieve the same goal?

Projects of retrieval and resurrection of ‘Other’ histories of liberation are likely to be confronted by numerous challenges pertaining to methodology and, given that this is India, research funding.

But there is something else, an equally formidable obstacle: a domineering right-wing that has turned the usurpation of nationalist history and its heroes into a dark art in the name of ‘correcting’ imbalances. The challenge, therefore, is to make the history of India’s battle against the raj inclusive without falling into Hindutva’s trap of discrediting bona fide nationalist icons or giving the narrative a divisive spin. Institutional affiliation may not get the inquisitive mind far on this quest.

Could the answer, then, lie in start-ups — but not the ones that the prime minister fancies? Two former students of Jadavpur University, for instance, are collecting and digitally recording relatively unknown anecdotes regarding the life and times of Bengal’s revolutionaries. The result is the fascinating ‘Agnijug Archive’, a rich repository of the life and times of freedom fighters who have been ignored in, or remain on the margins of, official pedagogy. The blooming of such local archives, funded by and disseminated within public circles, would not only address the anomalies in the narrative of India’s freedom struggle but also derail the right-wing’s plan of recasting this history along segregated, saffron lines.

This endeavour at re-presentation — democratisation? — of the anticolonial narrative would be a perfect way of honouring Mallu Swarajyam, the lady who, busy as she was fighting repression, could not raise the Tricolour on August 15, 1947.