1962: THE WAR THAT WASN'T By Shiv Kunal Verma, Aleph, Rs 995

Great battles are remembered for their victors, not their vanquished. So, it is perhaps no surprise that we can recall images of the Kargil war of 1999 or the earlier Bangladesh war of 1971, but not the Chinese conflict of 1962. There are deeper roots of our nation's forgetfulness. The brief undeclared war with China was an indictment of India's post-Independence government led by the charismatic prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, and our nation's woefully inadequate defence preparedness resulting in a massacre of our armed forces in a matter of days. The causes of that border conflict still remain and can become a flashpoint once again, as both India and China jostle to become global economic powers. Shiv Kunal Verma's recent book, 1962 : The War That Wasn't, is a timely reminder of the circumstances of that conflict and the "non-war" that followed. As Verma observes, "it is vital for future generations to understand the genesis and complexities of the conflict with China" because "nations that do not learn from history are doomed to make the same mistakes again."

To set the scene, we need to look back at the post-Independence euphoria of the 1950s when Nehru strutted the world stage as the pacifist leader of the newly-formed group of non-aligned nations. Nehru had engineered the Panchsheel Treaty with China that, he believed, would ensure peace with our massive neighbour. In the same spirit of appeasement, he acquiesced in China's annexation of Tibet and shrugged off the warnings from our army leadership that, with the Chinese border now abutting India's along a long line from the Karakoram range in Ladakh to Burma, the army was ill-equipped to defend such an extensive border. With a dangerous mix of hubris and naivety, Nehru believed that a non-violent nation did not need an army. In contrast, the Chinese leadership viewed Nehru with amusement and prepared for the challenge that was to follow.

The genesis of the border dispute was spread over several centuries with marauders criss-crossing the putative border with Tibet from the west and the Chinese from the east, while the country itself had porous borders along the south arising from trading, grazing of livestock, harvesting, and religion. The infamous McMahon Line drawn along the Himalayan peaks in 1914 was inherited by independent India but contested almost immediately by China, particularly after the annexation of Tibet. This became explicit by the late 1950s with China's construction of a highway through Aksai Chin, across the territory claimed by earlier treaties to be Indian. On Tibet's southern flank, along the border with what was then the North-East Frontier Agency particularly in the area of Tawang where historically there had been ambiguity in administrative ownership, the Chinese launched probing skirmishes to establish China's territorial claims. Yet, Nehru chose to play down these incursions, leaving the nation both in ignorance and in denial. He turned down a Chinese offer to exchange the disputed area in Ladakh for a settlement of the NEFA border.

To limit the scale of a possible armed conflict, the border between NEFA and Tibet had traditionally been policed by the paramilitary force of the Assam Rifles rather than the army. Under the pressure to respond to the embarrassment of the Chinese incursions, Nehru announced in Parliament, without consulting the army chief, General Thimayya, that he had placed the defence of the border area of NEFA directly under the military authorities. Conversely, Thimayya's views, expressed through a contemporary magazine article, was that he could not "envisage India taking on China in an open conflict on its own. We could never hope to match China in the foreseeable future." This weakness was compounded by the untried nature of the Indian army commanders who had no experience in modern combat in contrast to their Chinese counterparts who had learned from the bruising conflicts of their recent civil war and the protracted war against the latest equipment and military techniques of the American-led troops in Korea. This inexperience went to the very top when Nehru promoted General "Bijji" Kaul as chief of the general staff, although Kaul had no combat experience and had not even commanded an infantry company, let alone a battalion. Kaul's sole qualification was that he was Nehru's trusted man and so he had the ear too of the acerbic-tongued defence minister, Krishna Menon. Even the deputy chief of the Chinese army visiting India reported back to Chairman Mao Zedong that Kaul's "colleagues ridicule him as a General who has never fought a war."

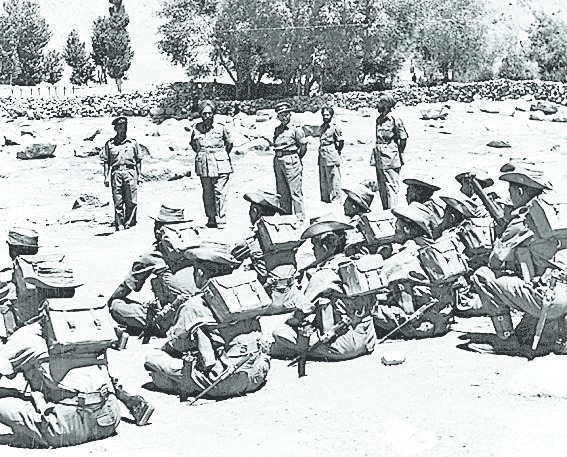

The ultimate instigation for hostilities was bizarre - a ten-fold exaggerated report by a border-post subedar of an apparent Chinese advance to the Indian border at Namka Chu in the Tawang sector. This triggered a muddled reaction down the long chain of the army's command stretching back to Delhi where the defence minister, Menon, held a meeting with senior army commanders directing that the Chinese were to be "thrown out". The reality was that the most senior commanding officer for the area, who attended Menon's meeting, had neither visited Tawang nor any other part of the NEFA. Troops rushed up to the border across hostile terrain and high altitudes. But they had neither the clothing nor the equipment to carry out such a directive. Airdrops of supplementary equipment were largely lost because of the parsimonious policies of reusing retrieved parachutes which consequently did not open. Local commanders at the border who did appreciate the ground realities and the foolhardiness of engaging the Chinese were ignored or shunted out. In their place, General Kaul was sent as the Nehru-Menon representative to enforce Delhi's misjudged directive. Crucially, Kaul's subordinate withheld from him the Intelligence Bureau's vital information that Kaul would be facing not just one company of the Chinese army that the local commanders imagined, but two regiments about ten times the size.

The Indian disposition was stretched along several kilometres of the south bank of the river, facing the Chinese army on the opposing ridge and the higher ground beyond. Our defence was so thinly manned that there were wide gaps. Ammunition was low with almost no mortar and certainly no artillery. A probing Indian foray across the river to bring flanking fire on the Chinese positions was pre-empted by such heavy mortar fire from the enemy that Kaul finally realized how desperately weak the Indian position was. Leaving his officers with instructions to hold the south bank at all costs - a suicidal mission - Kaul flew to Delhi to convince Nehru and Menon of the dire situation and the need to withdraw Indian troops to a safer rear position. Meanwhile the Chinese attacked with overwhelming force, encircling the Indian bunkers by surprise and annihilating them. Even the bravest defence was overrun, with Indian casualties amounting to a massacre. Verma's account of each action is detailed and descriptive but suffer from the lack of maps with matching detail, identifying each of the locations cited. For a lay reader, it would also have been helpful to have an appendix or a footnote quantifying manpower numbers of fighting units such as, say, a platoon, a company or a regiment.

Verma is extremely critical of officers commanding the Namka Chu imbroglio and his accusations of individual commanders are brutal. The unconditional and disorganised withdrawals were seemingly driven by panic rather than tactics. The subsequent fallback from prepared defences was symptomatic of the complete collapse of coherent thinking along the entire chain of higher command all the way back to Delhi, and was repeated over and over again in other sectors over the next few days. In a foretaste that seems to dog our military ability, Verma documents the deep infiltration of Chinese agents into our intelligence system such that they knew everything about our army deployment, almost to the section and platoon level, and "an almost uncanny psycho-analysis of Indian commanders". In contrast, we had little or no knowledge of either individuals or force levels opposing us.

Nehru's abrogation of leadership and the inadequacy of his army chiefs and top generals make for pitiful reading in the light of the massive loss of life of the rank and file thereafter at Tawang and with heart-rending bravery at Sela and at Walong. Verma's descriptions of the slaughter of our retreating troops are vivid and not for faint hearts. The numerous acts of courage in the battle evoke a mixture of pride, yet anger at the machinations at higher levels of command eager to save their own skins. After the Walong defeat, a colleague alongside Kaul said "that he sounded so desperate as to be almost demented." The tragedy was deepened by the denouement for Nehru's pacifist ideals when he had to undergo the humiliation of seeking air-force assistance from the United States of America before China's unilateral ceasefire and withdrawal.

Verma's meticulous detail of the battle lines is understandable for it honours the brave and the fallen. The problem is that it breaks the flow of his narrative style and confuses the bigger picture of the army movements as a whole. Nevertheless, the story is gripping and monumentally tragic. Current nationalistic fervour makes the Indian public belligerent to settle scores with our neighbours. The question left in the mind of the reader after the terrible debacle of 1962 is whether adequate corrective actions have been taken to ensure that such a failure does not happen again.