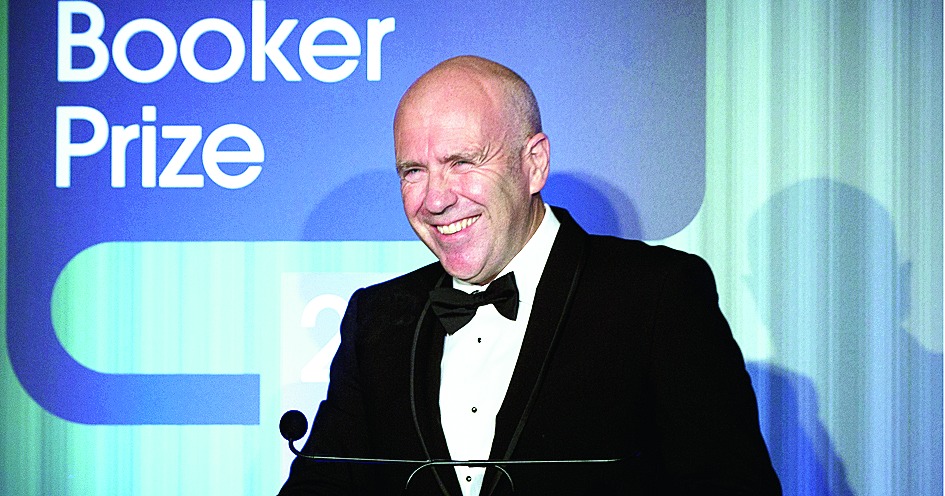

In one of his quotable interview quips, Richard Flanagan asserts that "a novel without structure is a jellyfish pretending to be a shark". In those terms, then, his latest novel, First Person, is possibly an amoeba pretending to be a jellyfish. It holds within its 400-page spread the potential to come in for the kill, but the periodic pulsing of narcissistic self-indulgence becomes a serious impairment to the fulfilment of evolutionary promise.

The book is wittily titled in that it draws its plot from a real episode in the author's life and promises to explore the fraught relationship between truth and fiction in books. Flanagan shows himself to be both participating in and mildly critical of the turn to autobiography in the book trade. His hero, Kif Kehlmann, is a 30-something aspiring Tasmanian novelist struggling under the weight of a substantial mortgage, baby daughter, wife expecting twins and unfinished first draft. Like the real Flanagan in 1991, then writing his own debut Death of a River Guide.

Kif is offered $10,000 to ghostwrite the autobiography of notorious Australian con man, Siegfried 'Ziggy' Heidl (the real John Friedrich), in six weeks. This puts Kif in a moral quandary, but consumerist necessity in the shape of double pram and washing machine prevails, and our hero comes to Melbourne to write Ziggy's story. This proves to be an unexpected challenge because Ziggy refuses to cooperate, talking in tangents and offering only 'slow-drip stories' instead of verifiable facts. Like the real Friedrich, Ziggy dies of a bullet three weeks into the process, leaving Kif (and Flanagan, or vice versa) to finish the book alone. The resultant real memoir, Codename Iago: The Story of John Friedrich, came to be called the "least reliable but most fascinating memoirs in the annals of Australian publishing" by The Australian. In the novel, Kif's encounter with mundane evil so thoroughly disenchants him that he abandons writing and becomes a successful producer of reality television. As the last sentence of the book informs us, he has no regrets.

Writers have always been aware of the crafted nature of their work and anybody who has posted a status message on Facebook would surely recognize the artificiality of 'authentic' self-presentation. That is probably why Flanagan feels the need to also work into the book something akin to a parable of good and evil in which evil triumphs. By signing his ghostwriting contract, Kif figuratively hands his soul to the devil. Man's (not woman's) fascination with death and violence - and Kif is, of course, a kind of Everyman - ultimately leads to a pervasive moral anaesthesia (typified by America) which Flanagan sees as a symptom of our times. This much-worked existentialist stand, too, would have been fine if the burden of all this evil were not placed squarely upon poor Ziggy. There are moments of sublime nausea, horrific descriptions of epiphanic violence, and a whole continent full of angst, but Ziggy, whom we are asked to think of as a contemporary Satan, is too thinly fleshed out to appear to be much of a menace. On paper, Ziggy is the ultimate postmodern criminal. His most terrifying characteristics are sheer ordinariness and a protean ability to reflect and facilitate the unacknowledged evil in his victims. There is a great, if not new, truth buried at the heart of this model of evil and Ziggy is reasonably successful in corrupting and disillusioning our present-day Faust. But rather than show Ziggy weaving his sinister spell, Flanagan endlessly tells us about Ziggy's effect on Kif: "The necessarily incomplete nature of Heidl's stories, rather than denying their supposed truth, instead confirmed it. ... as an instinctive ruse it was more than effective. For the challenge to reconcile such outrageous lies lay not with him, but with you, the listener" or "Conmen are after your money... But Heidl was also after something more. Heidl was after your soul."

Ziggy does not say much although he's never quiet. When he does, it is mostly peppered with 'quotes' from the fictional German installationist, Tomas Tebbe, who apparently inspired Nietzsche and who is obviously invented by Flanagan to showcase his own moments of inspired aphoristic reflection: "A life isn't an onion to be peeled, a palimpsest to be scraped back to some original, truer meaning. It's an invention that never ends" (incidentally, it is very interesting that the budding novelist Kif does not know the meaning of palimpsest). "The greatest of prophets has but the vaguest of messages, Heidl said. The vaguer the message, the greater the prophet." Borgesian metatextuality aside, it is only in a couple of instances of omniscience that Ziggy seems to truly exude the kind of malevolence he is credited with, but the effect is not lasting. Also, we simply do not care enough about Kif. His chronic self-loathing seems at times as self-indulgent as his creator's often tediously repetitive prose.

Flanagan is at his best when he does not succumb to the urge to be profound. The satirical asides on the book trade (Australian or American) are deliciously pungent and the all-too-brief flashes of humour quite incandescent (for example, the descriptions of the publisher, Gene Paley, who is frightened of books, the fictional Australian thriller writer, Jez Dempster, who is "like the Great Barrier Reef. Maybe you've never looked at a word he's written, but it's great to know he's there", the image of Kif's childhood mate Ray drinking steadily, "with the grim efficacy of a kitchen appliance that existed solely to empty glasses", Kif wrestling with his ancient Mac, the pretty young American bestselling autobiographer holding forth in a New York restaurant.) This book would have done much better if its first person narrator had decided to indulge more in dialogue than description, considered the longish short story format than the novel, and allowed himself more of the dark humour that is perhaps the only useful response to the important truths that he is at very great pains to articulate.