Neelam Katara's mission is not over yet. Her son Nitish Katara's killers have been convicted. But the fate of the convicts, Vikas and Vishal Yadav, is still not sealed. The Delhi High Court had upheld the trial court's verdict of 30 years' of imprisonment for the two. But she wants the death sentence to be handed down.

"If there is no death sentence by the Supreme Court, then the accused should be in jail at least for as long as they are alive," Katara says.

The sentencing, however, depends upon the discretion of the judges. Even in the worst of crimes, there is no uniformity in sentencing. "In some cases, the sentencing for murder is for 14 years or above while for others it is the whole of life. It varies from case to case," she points out.

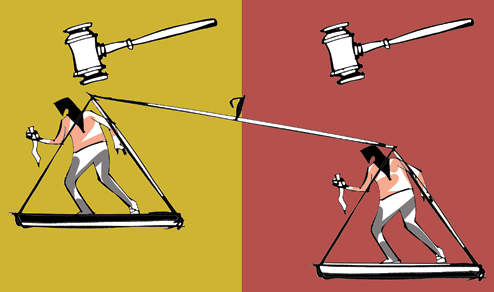

Not surprisingly, a demand for specific guidelines on sentencing is gaining ground. The lack of structured sentencing in India leads to a huge disparity in the delivery of justice, experts point out.

"At present, the quantum of sentencing depends upon the discretion of the judge because there are no specific guidelines. This often leads to a miscarriage of justice," Supreme Court advocate K.T.S. Tulsi says. "Justice should not depend on the subjective view of the judge. We need comprehensive guidelines on sentencing," he stresses.

Legal experts say that for many offences, the Indian Penal Code (IPC) prescribes only the maximum or the minimum punishment. It is the judge who decides what kind of punishment the offence deserves.

"There is a huge gap between the maximum and minimum punishment. As of now, a judge arbitrarily puts any punishment in between the maximum and minimum limits, which is vague and unpredictable," Tulsi adds.

With such a gap, sentencing differs from case to case. Some judges are seen as lenient and some as strict - and this makes a difference to the quantum of punishment.

The top courts too have referred to these anomalies in their judgments. In 2008, the Supreme Court, in the State of Punjab vs Prem Sagar & Others case, stated that the higher courts have come across a large number of cases that "show anomalies as regards the policy of sentencing", but the "quantum of punishment for commission of a similar type of offence varies from minimum to maximum; even where the same sentence is imposed, the principles applied are found to be different. Similar discrepancies have been noticed in regard to the imposition of fines."

In 2013, the Supreme Court, in the case of Soman vs State of Kerala, also observed that "giving punishment to the wrongdoer is at the heart of the criminal justice delivery but in our country, it is the weakest part of the administration of criminal justice. There are no legislative or judicially laid down guidelines to assist the trial court in meting out just punishment to the accused facing trial before it after he is held guilty of the charges."

The central government had earlier set up two committees to look into the possibility of framing specific sentencing guidelines on sentencing but no policy has been framed so far.

In March 2003, the Committee on Reforms of Criminal Justice System, known as the Malimath Committee, was established by the Union ministry of home affairs. The committee stated that in order to bring "predictability in the matter of sentencing," a statutory committee should be first established "to lay guidelines on sentencing guidelines under the chairmanship of a former judge of the Supreme Court or a former chief justice of a high court experienced in criminal law with other members representing the prosecution, legal profession, police, social scientist and women representative".

In 2008, the (N.R.) Madhava Menon Committee on Draft National Policy on Criminal Justice reasserted the need for statutory sentencing guidelines. In 2010, the then law minister M. Veerappa Moily had also stated that the government was looking into establishing a "uniform sentencing policy" in line with the US and the UK to ensure that judges do not issue varied sentences.

Madhava Menon, who founded government law schools in India, says that a national policy on sentencing will offer more alternatives in the matter of punishments instead of limiting the option merely to fines and imprisonment.

"In respect of the quantum of punishments, the need for constant review is to ensure that it meets the ends of justice and disparity is reduced in similar situations. Also, a policy is required to avoid short-term imprisonment and to prevent overcrowding of jails and other custodial institutions, to be rigorously pursued at all levels," Madhavan adds.

There is a need for institutional machinery involving "correctional experts" for fixing proper punishment, he says.

Many lawyers also assert that this broad discretion leads to the abuse of the sentencing process because of personal prejudices. "There is lot of room for a judge to use his or her own biases in pronouncing a judgment. For example, if the accused does not behave properly in the court room, that too can act against him. But if there is a rulebook, there is no room for personal bias," Bombay High Court advocate Farhana Shah asserts.

Activist Kavita Krishnan stresses that any guideline on sentencing should be framed after consultation with various groups of people who deal with criminal cases. "Each criminal case is different and the circumstances under which a crime is committed are also different. We should have exhaustive discussions on this among consulting experts working with prisoners at various levels," she says.

Tulsi believes that guidelines will be a deterrent to crime. "It will reduce crime, too, because people would know what crime would lead to what punishment. Now they know that there is no specific punishment and therefore there is ample room to get away," he says.

The Katara case has brought this issue back to the forefront. Now, the experts stress, the government needs to act.