THE EMERGENCY: A PERSONAL HISTORY By Coomi Kapoor, Viking, Rs 599

Nations, perhaps even more than individuals, need legends to live by. The Great War sustains Britain. Americans can't forget Nine-Eleven. India looks back gloatingly to those 19 months of repressive rule when, to cite the Miltonian adaptation of Coomi Kapoor's first chapter, Indira Gandhi plunged the country into "darkness at dawn".

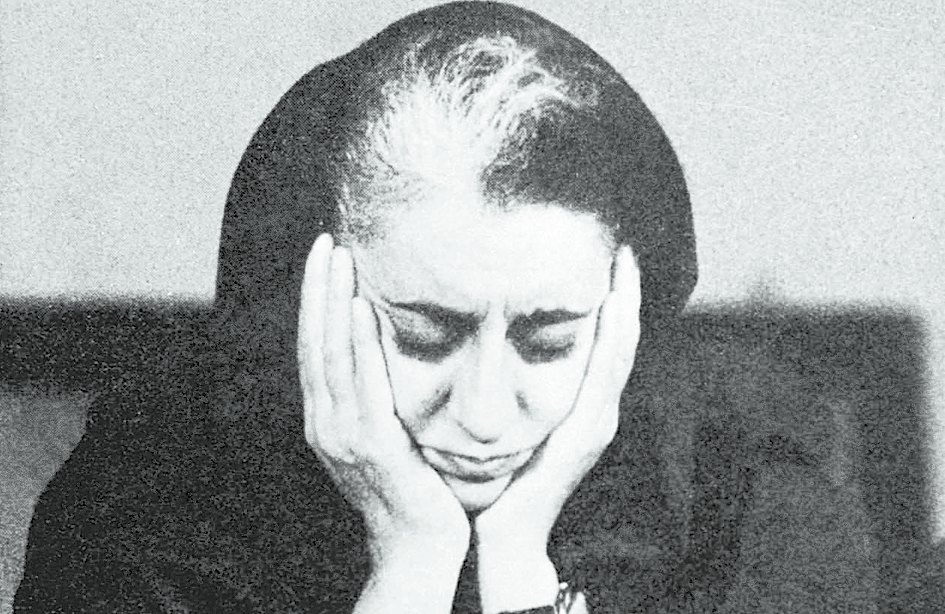

Her book is rightly titled "A Personal History". Kapoor writes sensitively about that traumatic period when the government targeted both her husband Virendra and her flamboyant brother-in-law Subramanian Swamy, and she herself suffered much. The saving grace was she had money and - more important - influential and resourceful connections. As a Parsee member of the Indian Civil Service, her father was of the crème de la crème of Indian society. Even without Virendra's political involvement, the Kapoors were assured of a ringside seat for the drama that unfolded on June 25, 1975. Siddhartha Shankar Ray's letter of January 8, that year "proposing the imposition of an internal Emergency" suggests the plotting began much earlier.

The result is a gripping account of all she saw, heard and endured. It's something Kapoor is good at. As Vinod Mehta noted in Editor Unplugged, "Coomi Kapoor's whispers column in the Indian Express (if you ignore the plugs for Arun Jaitley) are essential reading for any understanding of what is going on in Delhi beyond the headlines." (Jaitley repays the plugs with a glowing Foreword that also grinds his political axe.) Kapoor has thoughtfully added a chronological Timeline of Events as well as an Epilogue of potted biographies to explain where the dramatis personae disappeared when the curtain rang down. Both are useful since time has obscured the sequence and many of the details.

Despite this fond recreation, however, the enigma of the Emergency remains. The exchanges between Jayaprakash Narayan and Mrs Gandhi that played a crucial part in the run-up to the proclamation are shrouded in mystery. Did JP really want to stoke the fires of another national mutiny? Or were those exhortations to the armed forces and bureaucracy that provided politicians like Morarji Desai a bandwagon to jump on and Mrs Gandhi with the excuse she was looking for only part of the waffling that is the story of his life? Sanjay Gandhi's supposedly sinister role is still mainly gossip and rumour. Nor do we really know why Mrs Gandhi called elections when she did. These blanks remind us that she kept her own counsel on everything that mattered.

The author should also make some allowance for the fact that birth control and slum clearance were already avowed government objectives. It's only by inference we learn that there was a relocation plan too. Kapoor is also wrong in thinking Ray was either "Oxbridge-educated" or a leftist. He was called to the Bar from Inner Temple, and only vaguely liberal like others of his class and generation. Madhavrao Scindia, tragically cut off in the prime of life, should have been spared the ultimate insult of being called the hated Sardar Angre's "nephew". Kapoor must know this is untrue since the text implies a degree of familiarity with Angre who was an RSS stalwart. Other flaws can be blamed on her trusting nature. Being herself without guile, she accepts at face value the self-serving claims of ambitious operators. Balasaheb Deoras and Prabhu Chawla (whom she names) weren't the only turncoats. Mercifully, we are spared the antics of the junior journalist who leapt to editing a national daily thanks to Emergency patronage and invited ridicule afterwards by boasting of the demons he had slain in the cause of freedom. But she repeats S. Nihal Singh's uncorroborated boast of cheekily snubbing V.C. Shukla. Just as there are more dispossessed East Bengal zamindars in contemporary Calcutta than ever existed east of the Padma, there are more Emergency heroes today than dared squeak a protest at the time.

Kapoor relies heavily on the quickies (Janardan Thakur, the Mankekars, Uma Vasudev, C.G.K. Reddy) that flooded the market during the brief interregnum when the Janata sun shone and it was open season on the Gandhis. It would have been more to the point if, instead, she had cited the three-volume Interim Report of the Shah Commission of Inquiry at greater length and examined and interpreted its findings. Having sat through some of the hearings, this reviewer concluded the commission was a circus under a presiding officer who made little attempt at judicial rectitude.

Given her own politics and experiences, this was a book Kapoor had to write even if it's 40 years too late. The publicity it has received confirms the book clearly serves the political purpose of the government of the day. Now, that she has got it out of her system one trusts there will be no more "Daddy, what did you do in the Great War?" memoirs until someone can research a truly authoritative and objective account of how "one of the darkest periods in the history of independent India" (quoting Jaitley) came about and what really happened while it lasted.