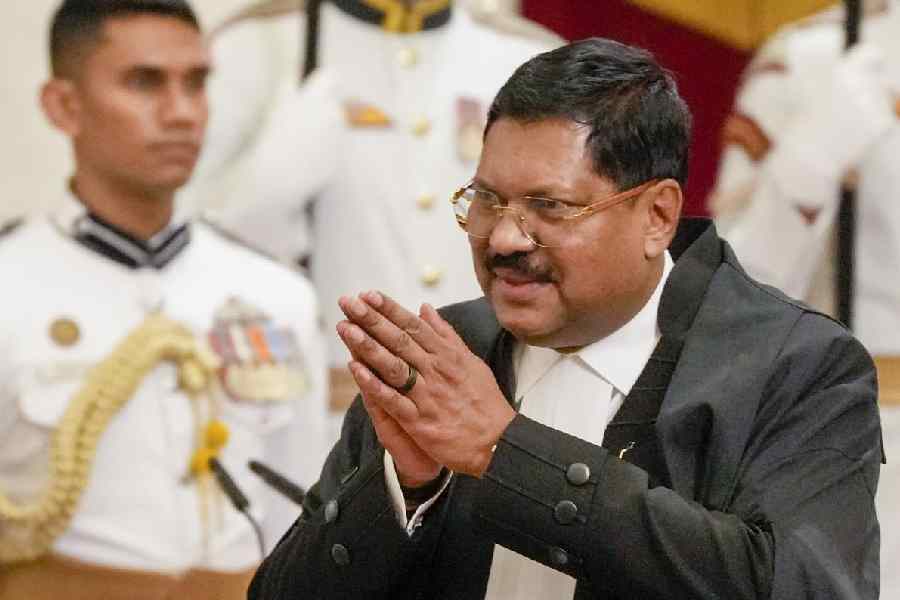

When Bhushan Ramkrishna Gavai took over as chief justice of India, the headline was not about his judicial record or his professional competence. He was near-universally referred to as the second Dalit and the first Buddhist CJI. This is unsurprising since minority CJIs are rare in a fraternity of judges dominated by upper-caste, Hindu men. But what does it mean to be a Dalit chief justice when D.Y. Chandrachud and U.U. Lalit are not primarily viewed as Brahmin chief justices and S. Khanna not a Khatri chief justice?

Highlighting Gavai’s Dalit identity is a symbol of the judiciary’s complex relationship with diversity. Diversity is good optics, but let’s not have too much of it please. When three women judges were appointed during the tenure of the former CJI, N.V. Ramana, much was made of this fact. But no woman has been appointed since that time. Caste is highlighted when Dalit judges tend to be appointed. But when judges from other under-represented Hindu castes are appointed, little is heard about their backgrounds. For religious minorities and representatives from smaller high courts, diversity is a double-edged sword. When K.M. Joseph’s appointment was stalled, a second Christian judge from Kerala was cited as a reason to rethink the recommendation. But when Justice A. Amanullah joined a list of highly- distinguished judges belonging to the Muslim community who were brought directly to the Supreme Court without serving as a chief justice of a high court or after a very short stint, no questions were asked. After all, unofficially, there has always been at least one ‘Muslim seat’ on the Supreme Court. But if representativeness is the objective, should it not be at least four Muslim judges, in proportion to their population?

But such a move would hard-wire diversity into judicial appointments. Such hard-wiring is antithetical to the self-image of the judiciary as a genteel environment of sophisticated arguments, polite enquiries, and the faintest taps on shoulders of prospective candidates. In such an environment, diversity serves a significant instrumental function. When the Supreme Court heard the constitutionality of the practice of instant triple talaq in Muslim personal law, the coverage was replete with how a Sikh chief justice together with a Muslim, Parsi, Hindu and Christian judge had sat in judgment. Similarly, when the question of whether it is constitutional to sub-classify scheduled castes into more specific castes for the purpose of reserving seats in government jobs arose, the judgment of the court permitting such sub-classification had much more legitimacy, with Bhushan Gavai writing a powerful, concurring opinion.

This instrumental utility of diversity has meant that merit is sometimes forsaken at its altar. A classic example was that of Baharul Islam, appointed by Indira Gandhi’s government to the Supreme Court almost a full year after he had retired from the high court. Islam was not only picked because he was a Muslim judge but also because he was only the second from the Northeast to serve on the Supreme Court. In the period since retiring from the high court, he had tried to return to the Rajya Sabha where he had earlier been an MP from the Congress Party. However, he failed to get elected. Instead, he was brought to the Supreme Court. On the Bench, he did very little that was notable, except for a judgment upholding the decision of the then Congress chief minister of Bihar, Jagannath Mishra, to withdraw criminal cases against himself. That matter had to be reviewed by the Supreme Court after Islam’s retirement. By that time, Islam had got what he was always seeking — a Rajya Sabha seat — where he served till 1989. It needed a long line of distinguished judges from the Northeast on the Supreme Court to undo the damage that a tokenistic appointment like Islam’s had wrought.

Such one-off damage — which ironically happens quite often — means that the larger issue of diversity is routinely conflated with the performance of these judges. As a result, the issues of systemic unrepresentativeness and exclusion are obscured by focusing on isolated events. Data on women in the judiciary illustrate the point. Women’s representation in the lower judiciary follows a pattern consistent with broader trends in employment: when selection is based on merit, women do reasonably well. At the district and subordinate court level, where appointments are made through competitive examinations, there are 7,852 women serving as judges, accounting for just over 40% of the total working strength. On the contrary, in the high courts and the Supreme Court where elevation is based on nomination, initially by a judges’ collegium and then endorsed by the executive, there are only 109 women judges in the high court (a shade less than 10%) and only one woman judge in the Supreme Court (less than 5%). In these upper echelons, neither merit nor diversity appears to carry much weight.

Beyond optics and symbolic appointments, there is also little evidence of a genuine institutional commitment to making the judiciary more inclusive. This is clearly evident from the fact that data on Dalit judges in various courts are seldom collected, except when there is reservation for Dalits in the judiciary of that state. In 2018, data about the lower judiciary’s composition was available for only 11 states. Of the 3,973 judges in these states, 563 (14%) were from scheduled castes, 478 (12%) from scheduled tribes, and 457 (12%) from other backward classes, mostly owing to reservation. Overall, there is no systemic move towards increasing Dalit representation in the judiciary. Such a move need not always take the form of reserving seats on the bench. Collecting data, organising seminars on contested questions of merit and representation, building consensus on a more representative judiciary would all go a long way. Caste should not be a card to be played when convenient. It should be a commitment towards a more inclusive judicial system which Indians can call their own.

This is especially so because the Supreme Court is no longer an institution that only adjudicates technical questions of law. It is a permanent fixture in the imagination of an Indian citizen — granting bail to the incarcerated, dismissing chief ministers, advising restraint to the outspoken, and supplying a voice to the silent. While excluded sections might have once felt great pride if one of their own made it to the very top of the Supreme Court, now there is not just pride but also an active, albeit vicarious, involvement in the issue at hand. When the Supreme Court steps in on matters of great political moment, many of which are questions of governance and not strictly of law, it matters very much who the judges taking these decisions are.

That is why having Bhushan Ramkrishna Gavai as a Dalit CJI matters. But what matters equally is to reach a point in time when Justice Gavai would simply be referred to as yet another CJI like his non-Dalit predecessors were. That would not be tantamount to erasing caste from the public sphere. It would rather signal the arrival of a moment when India is respectful and welcoming of a Dalit judge’s caste identity but does not make it his/her defining feature.

Arghya Sengupta is Research Director, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy. Views are personal