The lesson from Gurdaspur is that a comprehensive review of the Narendra Modi government's Pakistan policy involving the broadest possible consultations can no longer be put off. The aim of such consultations should be to reach a national consensus on dealing with Pakistan: in broad terms, such a consensus existed until not very long ago. A starting point for any such review ought to focus on the Ufa meeting between the prime ministers of India and Pakistan earlier this month.

Why did the meeting between Modi and Nawaz Sharif on July 10 raise expectations sky high, only to degenerate into a farce even before Modi returned home from that meeting? The answer is plain as day to practitioners of foreign policy who understand Pakistan. Unfortunately, in the present environment in New Delhi, those in government who could have predicted the descent from the euphoric heights of Ufa to the anger and frustration in Gurdaspur will not speak up.

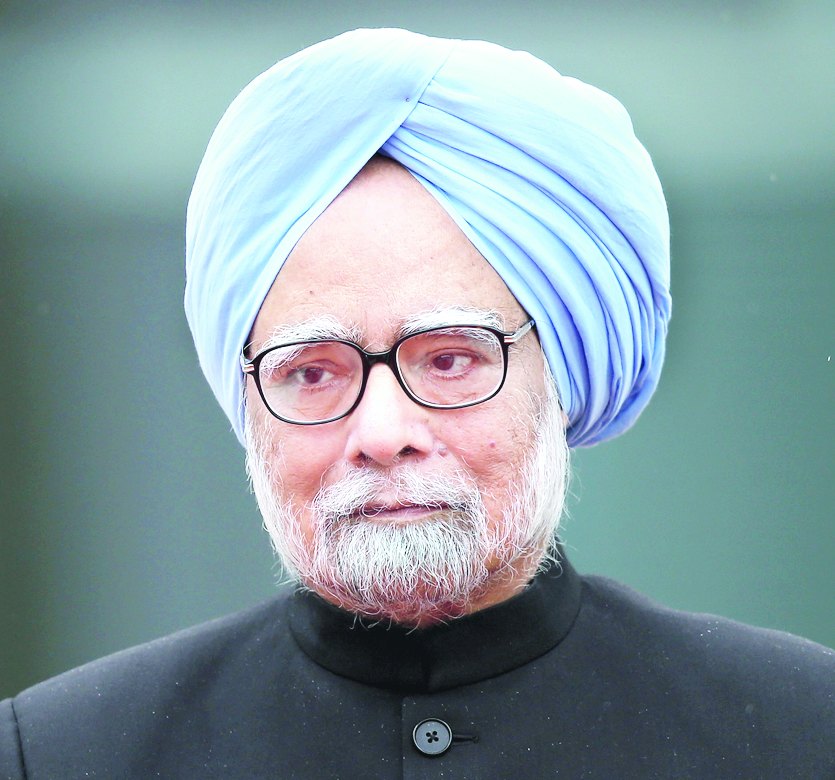

They will not speak up because the fundamental flaw in contemporary dealings with Pakistan is in the composition of Modi's administration itself. And it is beyond the pay grade of those who can administer correctives to point out this fatal flaw although it is serious enough to constitute a threat to the nation's security and well-being. It is not as if the previous United Progressive Alliance government did appreciably better in dealing with Pakistan - especially in its second five-year term in power. But the UPA was able to 'manage' relations with Pakistan: there were no memorable successes, but the Manmohan Singh government did not go to war. Nor did it lower India-Pakistan relations to its nadir.

The reason why Singh was able to manage relations with the country's most troublesome neighbour of all was because he had two persons in his inner circle who were so thorough with everything to do with Pakistan that he could entrust the UPA government's dealings with Islamabad to these two men. Between them they knew how to maintain a modicum of engagement with Pakistan, at multiple levels, that the darkest clouds on Wagah's horizon inevitably had the tiniest of silver linings. Any such silver lining was an insurance against another war in the sub-continent, which would set back India's development goals and hopes of emerging as a responsible global power.

Satinder Lambah was unflappable even during the most challenging moments on his watch when he was high commissioner in Islamabad. And he was so sure-footed that he did not hesitate to tell off his boss. The foreign secretary, at that time, was totally bereft of any first-hand knowledge of Pakistan other than what he gained from playing golf with Islamabad's then envoy in New Delhi, against the advice of the security chief in the ministry of external affairs.

It was after a flaming row with the foreign secretary that Lambah one day decided that he had had enough. He picked up the phone, talked directly to P.V. Narasimha Rao, then prime minister, and told Rao that he could not continue in Islamabad. Rao shifted him as ambassador to Bonn forthwith, a posting that signalled appreciation of his contribution to Pakistan policy. It was to Lambah that Singh turned when the UPA government needed a special envoy for Pakistan and, by extension, to Afghanistan.

Equally, Singh relied on Shivshankar Menon, his national security adviser, who earlier served as high commissioner in Islamabad before being appointed foreign secretary. For many Indian diplomats, intelligence personnel and others involved in crafting New Delhi's approach to Islamabad, a major difficulty is to come to terms with changes in the psyche of Pakistan and its effects on policy-making in Islamabad.

Hardliners tend to live and die as hardliners. Those who are optimists on Pakistan never give up on their expectation that it is possible to do normal business with Islamabad. Menon's great asset was that he cut himself loose from a dogmatic approach when he was posted as high commissioner: some say he applied a lifetime of experience in China and looked at Islamabad with an open mind. Lambah and Menon provided most of the inputs for the UPA's policy towards Pakistan.

Modi is disadvantaged by the complete absence of a competent source of advice on Pakistan at an institutional level. This lacuna is unprecedented for any previous prime minister. Beyond institutional support, there is no one with ready and regular access to Modi who has his confidence, who can look him in the eye and tell him plain truths about Pakistan or the fallout of geopolitics on Kashmir the way Lambah could do with Manmohan Singh.

Since becoming prime minister, Modi has enjoyed the benefit of advice from two successive foreign secretaries. They have both been competent in their own ways, but Pakistan has not been their strength. Neither Subrahmanyam Jaishankar nor Sujatha Singh dealt with Pakistan in any depth until they were chosen to head the diplomatic service. In their short time as foreign secretaries, neither of them has had the opportunity to reflect on the complexities of this aspect of neighbourhood diplomacy, the kind of competence that someone like J.N. Dixit acquired after decades of dealing with Pakistan.

To make up for this dangerous shortcoming in 'Modiplomacy' the news leakers in Modi's government have woven fanciful tales about Ajit Doval, the national security adviser, and dressed him up as an expert on Pakistan. It is true that he had an unusually long posting in Islamabad, but the stories which have been appearing in the media about his undercover activities in Pakistan during those years would have made Ian Fleming dedicate some of his James Bond books to those in New Delhi whose spin has sadly made Doval the last word on Pakistan in Modi's officialdom.

Doval's job at the Indian mission in Pakistan was primarily to manage the high commission's large contingent of India-based security guards. In volatile neighbouring capitals like Colombo and Islamabad, among others, the security of the high commissioner's residence, the mission compound and other Indian properties is not entrusted to local people for obvious reasons. That meant Doval prepared the shift-duty rosters of policemen and paramilitary personnel sent from India for such work, made sure that they did not fall into honey traps or take bribes - from the Inter-Services Intelligence, in Pakistan's case - to plant a listening device in the deputy high commissioner's drawing room or sell their quota of duty-free liquor from the commissary to well-heeled, but alcohol-starved, Pakistanis.

This is not to disrespect Doval's widely-acclaimed capabilities as an operations sleuth and a counter-intelligence expert, but he did not acquire or practice these skills in Islamabad. That was the job of other officers from the Intelligence Bureau and the Research and Analysis Wing who were posted in Islamabad then. This is being written from intimate knowledge of the working of Indian diplomatic missions across the world gained from this columnist's stay abroad for 26 years as a foreign correspondent. Among those in New Delhi who served with Doval in Islamabad, the current media spin about Doval's cloak-and-dagger activities from that time is now the subject of great mirth.

Sadly, Modi has bought into his own government's spin about Doval, which was meant for the public, so that Doval can easily slip into the shoes of his illustrious predecessors like Brajesh Mishra and J.N. Dixit. Someone like Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Jaswant Singh or Yashwant Sinha would not have been taken in by these fanciful tales about the present national security adviser. As an outsider in Delhi, who has held no elected or administrative job other than Gujarat's chief ministership, Modi is unfamiliar with such matters.

Anyone who has dealt with intelligence officers of Doval's seniority also knows that they gain their clout in the system by making their bosses vulnerable. His predecessor, M.K. Narayanan, could do that as an IB veteran to Rajiv Gandhi, another outsider to the system in 1985. As an operations man who cannot scale strategic heights, Doval now compensates himself by making ill-advised threats against not only Pakistan but also China. And the prime minister in good faith, goes along. Predictably, the upcoming meeting of Indian and Pakistani NSAs is, therefore, likely to be unproductive, although there will be more of Ufa-style spin. Doval hopes to pin down his counterpart, Sartaj Aziz, on terrorism, and Aziz is preparing to do the same to Doval, but with his characteristic finesse and erudition. If that happens, more Pandora's boxes in South Asia may be opened where none was necessary if only the government had a Lambah or Dixit by the prime minister's side.