Only 10% of India forms part of the consuming class while a billion of their peers have no purchasing power, except for bare essentials. Further, this upper middle class is not “widening” but “deepening”. In other words, the cohorts of the already wealthy are expected to get wealthier, but with no addition to their numbers. These are the findings of a research report on India’s consumers released a few days back by the venture capital firm, Blume.

We can also add equally startling data points from the recent Economic Survey released by the Central government. Only 8% of Indian graduates (our creamy layer) hold jobs matching their education credentials. The vast majority of our workforce (88.2%) is concentrated in “low-competency occupations”, largely in the informal sector. Unsurprisingly, a 2020 World Economic Forum survey of 82 countries held that India ranks among the bottom seven countries for “inter-generational upward mobility”, flanked by Pakistan and Bangladesh.

Why do the vast majority of Indians remain deprived of any significant purchasing power or opportunities for productive employment? There are several reasons. But let’s focus here on one key aspect: the political economy of finance. By this we mean, who gets access to the State-constructed taps of money flows (bank credit) and who remains deprived of it.

It might be instructive here to compare India’s political economy with those of the advanced countries of East Asia as well as with that of galloping China. These countries have managed to widely distribute purchasing power and provide employment to their population through a modernised and expansive small and medium enterprises sector, particularly in manufacturing. A critical instrument for nurturing the dynamism of their SME sectors have been the policy of generous provision of State-directed bank credit at favourable terms.

Let us briefly survey some data taken from a 2022 Asian Development Bank report. The share of employment provided by the SME sector, out of total employment, stood at 70% for Japan, 89% for Korea, and 90% for China. In India, the share of employment was only 40%. The latter figure might also be wildly misleading because unlike the competitive medium-scale enterprises of East Asia, the bulk of the SME employment in India revolves around micro units, which can barely employ a handful of workers and remain confined to obsolete technology.

A critical reason why SMEs fail to scale up and modernise is the persistent discrimination in the provision of bank credit. The value of total outstanding credit to the SME sector in China is more than 120% of the size of the GDP; in Japan and Korea, it is roughly equal to the size of GDP. Meanwhile, in India, the total outstanding credit to SMEs only adds up to 8% of the GDP. Similarly, in China and Korea, almost half of the yearly bank credit is allocated to the SME sector. In India, the allocation is a meagre 5% of total non-food credit, down from 15% in 1990-91. Worse, SMEs are charged exorbitant interest rates: an average of 11% here as opposed to 4% in China, as the economist, Jayan Thomas, has written.

Who does the banking sector serve then? In boom periods, banks provide credit to the country’s “oligarchic capitalists”, as the Harvard economist, Michael Walton, has described them. This is the faction which had clogged up the banking system with a mountain of bad debts, leading to a massive loan write-off of more than 10 lakh crore. In lean periods, the banking sector serves the upper middle class’s myriad desires — for consumption (retail loans) as well as for speculative rents (loans for buying financial and real estate assets).

The third faction that the bank credit serves is the ruling party for its financing needs. The electoral bonds saga had shed some light on this collusive relationship between the political and the oligarchic elite. As Walton has demonstrated, over half of the wealth accrued by India’s billionaires between 1996 and 2013 came from “rent-thick” sectors (sectors with high levels of extractive rents derived from links to the State). Given the extensive flow of funds within the State-corporate nexus, little wonder then that the 2024 elections were dubbed by The Economist as the world’s most expensive polls.

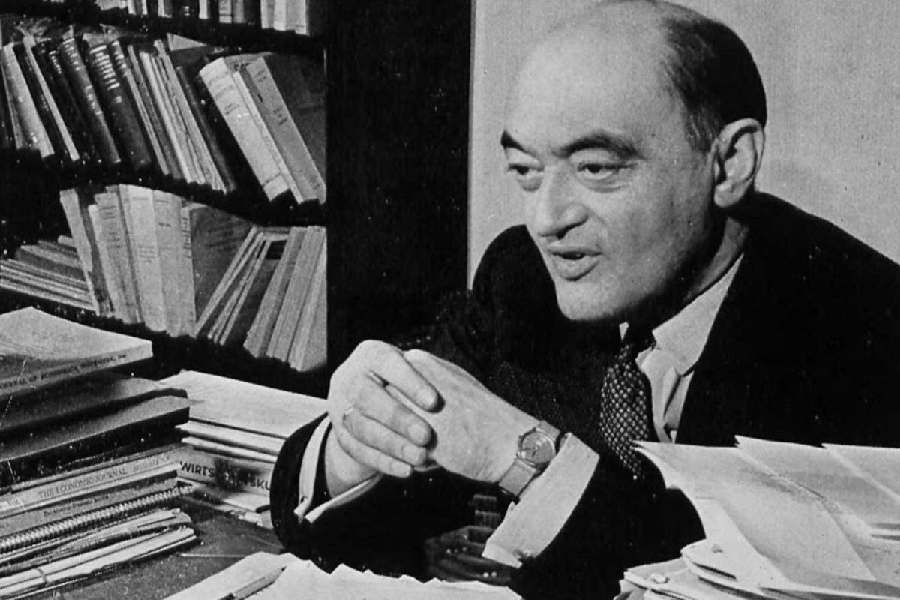

It is this alliance of a rentier political elite, a co-opted professional middle class, and oligarchic capitalists which shapes the political economy of Indian finance. Why has the entrenchment of this alliance led to the present state of stagnation? To understand this point, let us turn to the political economist, Joseph Schumpeter, the prophet of “creative destruction”, and his theory of economic development.

Schumpeter is especially relevant here because he directly influenced the Japanese model of high-investment-led rapid industrialisation, which subsequently became the pre-eminent model for South Korea and China. Many of the top planners and policymakers of Japan in the 1950s and the 1960s (some were Schumpeter’s former students) drew on his insights on “credit-creation”, “forced savings” and “technological upgradation”. This has been extensively documented by the historian, Mark Metzler, in his book, Capital as Will and Imagination: Schumpeter’s Guide to the Postwar Japanese Miracle.

At the heart of the process of development, for Schumpeter, lies the innovative figure of the entrepreneur. Most businessmen, he reminded, are not entrepreneurs. An entrepreneur is someone who creates “new combinations” from the existing pool of resources of land, labour and raw materials. This new combination can mean anything, from the introduction of a “new quality of a good” or “a new method of production” to the “opening of a new market” or the “conquest of a new source of supply of raw material”. The bottom line is that the new combination must translate to a net value addition to the social stream of goods and services.

A less propagated aspect of Schumpeter’s model of development is the importance he confers on the banking system and a facilitative State. The crucial role of banks lies not only in creating new purchasing power (credit) for the entrepreneur to implement his “new combinations” but also in drawing purchasing power away from the existing stream of goods and services.

Credit-creation tends to be inflationary in the short run and it forces less-productive firms and consumers to economise on their share of purchasing power. This is the “forced savings” effect, a typical feature of East Asian economies. For Schumpeter, “a different employment of the system’s productive powers” “cannot be achieved otherwise than by a disturbance in the relative purchasing power of individuals.”

Credit creation need not be financed with prior savings because as per Schumpeter’s heterodox view, “banks create credit” rather than “lend the deposits that have been entrusted to them”. As a former banker and finance minister, Schumpeter knowingly asserted that banks were not so much a “middleman in the commodity ‘purchasing power’” as they are a “producer of this commodity”. The Bank of England recently confirmed Schumpeter’s insight by noting that the “majority of money in the modern economy is created by commercial banks making loans,” correcting “some popular misconceptions — banks do not act simply as intermediaries, lending out deposits that savers place with them… nor do they ‘multiply up’ central bank money to create new loans and deposits.”

At the end of the credit process, the entrepreneur not only returns to the social stream the value of the purchasing power he had previously borrowed but also expands the existing stream of goods and services through the process of technological upgradation. Thus, the credit-creation process, if used for productive purposes, tends to be deflationary (driving down long-run prices) instead of inflationary.

It was recognised by Schumpeter that the entrepreneur need not be an individual. It might be a management group, or even the State — what he termed as the “entrepreneurial state” — provided it takes the lead in the process of innovation. Several economists have also documented the footprint of the Schumpeterian model on the Chinese model of development (Hansjörg Herr, Leonardo Burlamaqui). This East Asian entrepreneurial State has birthed the world-beating Korean, Japanese and Chinese firms whose functioning can be instantly recognised in this Schumpeterian model.

The rentier Indian State, meanwhile, nurtures only our sluggish and overly-protected conglomerates. The only two exceptions are the dynamic, export-oriented sectors of information technology and pharmaceuticals, which had been spun out of research laboratories in the State sector. Indeed, the patented drugs of our pharmaceutical corporates still come out of the CSIR-IICT institute of Hyderabad. These sectors have served well the interests of the educated middle class. The stagnant broader majority, battered by the successive blows of GST, demonetisation and the Covid pandemic, remain condemned to suffer the destructive end of the ‘creative destruction’ process.

Asim Ali is a political researcher and columnist