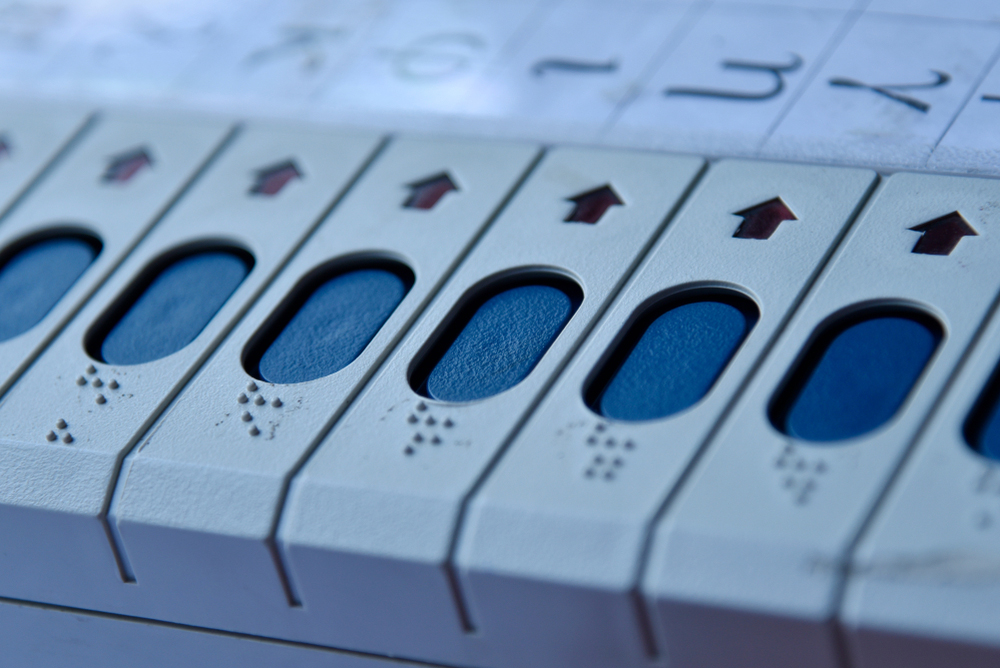

My parents must be thanked for giving me a name starting with the letter ‘A’. There’s a possibility that my name will figure in the topmost position of an electronic voting machine. Section 38 of the Representation of the People Act, 1951 requires that the order followed for preparing the list of candidates be alphabetical. On this list, national parties are followed by regional parties; then come the registered parties followed by independents. Since late 2013, Nota has been the last button on the EVM.

Sonia Gandhi, Sharad Pawar, Mamata Banerjee, Mayawati, N. Chandrababu Naidu and other leaders have raised concerns about EVM tampering. But not much attention is paid to such other aspects as an EVM’s design. ‘Name-order effects’— the relationship between the position of a candidate’s name on the ballot and his/her electoral success — has been well-established in political science literature. The victory of George W. Bush over Al Gore by a slender margin in the US presidential election in 2000 may have kindled the media’s interest in ballot paper design but the potential of the ballot order to influence electoral outcomes has been recognized by political scientists for nearly 100 years. In the United States of America, candidates have been known to change their names to take advantage of alphabetical listings. Several recent studies have found that first-listed candidates were at an advantage in the ballots in US state and federal elections as well as in polls to the Australian House of Representatives.

In his seminal article in American Journal of Political Science in 1975, Delbert A. Taebel showed that not only did candidates listed first enjoy a favourable advantage but this advantage was also greater in contests further down the ballot. In their 2004 article in The Journal of Politics, Jonathan G. Koppell and Jennifer A. Steen analysed data from New York City Democratic primary contests in which the names of candidates were rotated on the ballots by precincts. In 71 of 79 contests, candidates received a greater proportion of votes when they were listed first compared to any other position. And for 7 of these 71 contests, the advantage of first position exceeded the winner’s margin. Koppell and Steen concluded that the ballot position would have determined the election’s outcomes if one candidate had held the top spot in all precincts. Recently, a group of researchers from Denmark’s Aarhus University found that candidates listed first on the ballot paper regularly receive more votes than other contestants in first-past-the-post and proportional representation systems of voting.

Where does the advantage of the the first-listed candidate come from? Does it cost all other candidates dear, or does it cut the votes of some specific candidates?

California randomizes the order of candidate names on ballots by district, thus creating an interesting source of valuable data. In 2010, Yuval Salant of Kellogg School of Management and Marc Meredith at the University of Pennsylvania analysed the results of elections to city councils and school boards in California and concluded that in one-tenth of the cases, candidates listed first won because he/she was so listed, and that the first candidate advantage comes primarily at the expense of candidates listed in the median ballot position.

Is there any significant advantage of the first position in the Indian system as well? As Taebel observed in 1975, the name-order advantage didn’t hold when voters had high recognition of candidate names. In Indian politics, people often vote for the party symbol without even knowing the credentials of the contestant. In some other cases, the personalities of the candidates play a big role. So there might not be much significant EVM-position advantage here. However, in the interest of democracy, we need a detailed study. If significant first-listing advantage is observed in India, where personalities and party symbols dominate electoral events, the system of listing of names in EVMs maybe changed.