|

Rabindranath Tagore: an illustrated life By Uma Das Gupta, Oxford, Rs 250

The most attractive feature of the volume is its size. Svelte, trim and surprisingly light, it promises to deliver an illustrated life of Rabindranath Tagore in 142 small demy pages, with two more pages introducing the author, Uma Das Gupta. Das Gupta’s interest in Tagore’s ideas of education and the evolution of Santiniketan, Sriniketan and Visva-Bharati has already yielded a number of works, among them Rabindranath Tagore: A Biography, in 2004. A new work, evidently on the same theme, Rabindranath Tagore: An Illustrated Life, in 2013 would suggest an urgency to publish again, maybe with new material, or a new approach. That is always possible with Tagore. Das Gupta’s sources are particularly promising — the corpus of Tagore’s writings in English, his letters to friends in the West, for example, some manuscripts, articles from the Visva-Bharati Quarterly and the Visva-Bharati Bulletin, among others. Yet these are not very different from those used in the earlier biography, neither can it be said that the approach is particularly fresh or novel. For in the present work too, Das Gupta concentrates on Tagore the builder of institutions as she had done earlier. It is very obvious that this is where her interest lies.

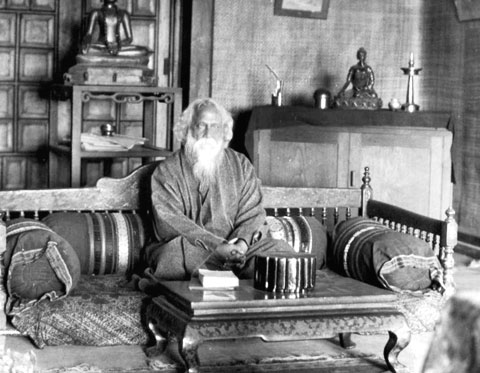

So perhaps the title holds the key. “An illustrated life” suggests, in a general way, at least two things. One, that the focus would be on pictures intricately related to the narrative and, two, that the production would be geared to the proper presentation of the pictures. It cannot be said that the present volume satisfies either of these expectations. To take the second point first, the production values of the book are terrible. Even if there are some rare photographs in the Santiniketan-Sriniketan sections — the photographs and sketches in the other sections are familiar and spasmodic — they are all obscured in what is apparently the dusty darkness of the past. The reproductions possibly could not be worse. The focus on “illustrations” is further undermined by editorial unevenness and sloppiness in the captions. It is alarming to find a famous profile of the young Tagore by his nephew, Gaganendranath, attributed to Jyotirindranath, his brother. The “illustrations” are not confined to pictures of people and sudden book covers. Quotations — the narrative is peppered with quotations — from poems, whether written by the poet himself or translated from the Bengali by the author or someone else, are obscured by some kind of leaf-and-tendril design in the background of the verses, a visual horror that makes discerning the lines quite a challenge.

As for pictures being intricately related to the narrative in order to make an “illustrated life”, it is the nature of the narrative that has to be looked at first. The first few chapters, from Tagore’s childhood to the chapter entitled “Becoming a humanist: ebar phirao morey” — two-and-a-half pages of which are taken up by the author’s translation of the poem, “Ebar phirao morey”, with the excruciating climbing vine behind it — tell the story in a slightly disjointed, overlapping manner, as though the narrator is in a hurry to get over with the preliminaries and cut to the chase. Das Gupta is not too bothered about facts here: Tagore, she says, was brought up with two of his nephews, both a little older. Satyaprasad was Tagore’s nephew, it is true, but Somendranath was his immediately older brother and the first ardent admirer of his juvenile poetry. Since this is an “illustrated” life, it may be mentioned that the three boys are seen together with Srikantho Sinha in what is believed to be the first existent photograph of Tagore. This picture is absent in the book, although a cut-out of Tagore’s figure alone has been carved out from it and included.

The pictures chosen for these chapters, too, give the sense of being hastily strewn around. Only a very few can be called rare. The photograph of Satyendranath and Gyanadanandini as a couple is not very common, neither is the delightful picture of Dwijendranath enjoying a ride in his three-wheeled vehicle. An overwhelming number of book covers have been selected for some reason. With the production being what it is, these just provide rectangular blurred spaces on the pages from time to time. Some of these are covers of those works Das Gupta chooses to summarize, such as Gora, Chandalika and Achalayatan, in order to show how Tagore’s political and social ideas developed over time.

Cutting to the chase means getting to the core of Das Gupta’s interest: the building of Santiniketan, Sriniketan and Visva-Bharati. In this “life” of his, Tagore is barely visible as a poet, composer and creative writer; it is his educational and political ideas, his social vision and his “universal humanism” that are important. Das Gupta’s account of these is quick and comprehensive, heavily dependent on long quotations and a slightly reductive commentary. Informative, although not stimulating. The pictures in these chapters could have been the best, being less familiar and often full of many interesting personalities and special activities, but it is impossible to discern much in their uniform gloom. Among the following chapters, the one on Tagore’s travels is once again untidy and repetitive, but Das Gupta is here able to connect his restlessness with his perpetual rebellion against all things fixed. The other chapter on Tagore’s painting we could have done without. The chapter on the man’s legacy makes an effort to pretend that the book was really about the whole of Tagore’s life.

Should this book not have been called something else? The word, “life”, raises certain expectations of comprehensiveness. Does an author, or editor, have the right to mislead the reader or buyer? The aspects of Tagore that Das Gupta emphasizes are very important, even if she has done it before, but that cannot be represented as the whole of his thinking life. Das Gupta’s theme could have made a separate, perfectly valuable, book. And the adjective “illustrated” in the title is a shabby trick. A production of this kind makes certain questions unavoidable. Do our scholars, researchers, editors and publishers have no responsibility towards their buyers? Is it enough just to talk about Tagore’s ideals in pious terms while completely ignoring his professionalism and ethics at every step, and using his name as a commercial open-sesame?