Apart from national flags and anthems, all nation-states hold dear to them certain phrases, logos, visual cues, slogans, rallying cries and the like. In Indian history, three such slogans and visual icons have been the most frequently used — Vande Mataram, Bharat Mata, and Jai Shri Ram. They are not of the same antiquity, and their usage and capacity to charge patriots, soldiers, devotees, rioters and so on ebb and flow over time. But one or more is always present within our quotidian sensory universe — the sounds we hear, the news we read, the anxieties we fret over, the fights we pick. What’s the big deal about this triptych?

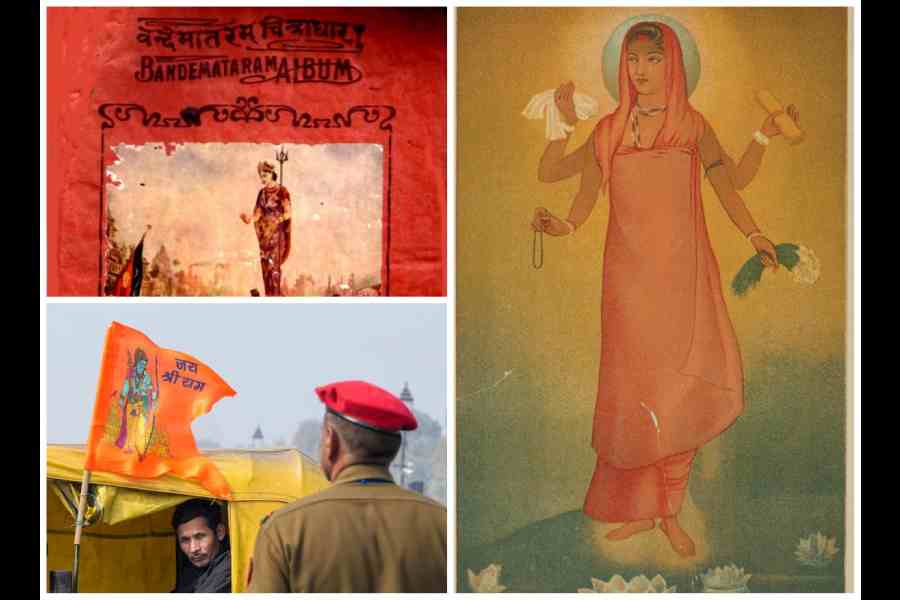

The oldest of the three, Vande Mataram (A Hymn to Mother), has seldom been free from controversy. Composed by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee in the 1870s, it made its first public appearance in his novel on the Sannyasi rebellion, Anandamath, in 1882. Exalted to a high pedestal by Rabindranath Tagore (who sang it for the first time in 1896) and Aurobindo Ghose, and used as an inspirational phrase from the 1890s right down to Independence, the chant of Vande Mataram by freedom fighters and revolutionaries served as both a rallying call and a pledge of loyalty to the nationalist cause.

However, as Sabyasachi Bhattacharya’s book, Vande Mataram: The Biography of a Song, documents, even in the early decades of the 20th century, the allegedly ‘idolatrous’ character of the song’s imagery created misgivings in some quarters. In the late 1930s, a section of Indian Muslims opposed the idea of Vande Mataram as a national song, contending that it was an evocation of Durga and part of a novel that was antagonistic to Muslims. This angered the Hindu nationalists but, at Jawaharlal Nehru’s request, Tagore suggested a solution, recommending the adoption — as the national song — of the first two stanzas of Vande Mataram. These were independent of the remaining stanzas and of the context of their placement in the original novel but still represented the themes of devotion and sacrifice. The Indian National Congress adopted an expurgated version as the national song, a process of ‘secular cleansing’ that opened the way for opportunistic political appropriation and the ascription of national or communal meanings to the song ever since.

Such manipulation of meanings applies also to Bharat Mata, one of the most enduring images of Indian nationhood. Though supposedly a unifying allegory, it can be polarising in the interpretations of its visual representations. In recent months, it has been at the centre of an unsavoury controversy in Kerala where the governor placed a portrait of Bharat Mata — adorned with a saffron flag — at an official event, prompting several leaders of the state’s ruling Communist Party of India (Marxist) to protest that the use of a very specific iconography amounted to a partisan insertion into a secular frame.

First painted by Abanindranath Tagore in 1904, Bharat Mata was an evocative and spiritual representation of India as a mother goddess. Over time, however, her visual depictions were reconfigured by numerous other individuals and organisations, adding saffron flags, maps of ‘Akhand Bharat’, and references to Hindu mythological trappings as well as India’s political history. Sumathi Ramaswamy’s book, The Goddess and the Nation: Mapping Mother India, provides many examples of such visual interpretations of Bharat Mata — as a nurturing mother holding symbolic objects like a sheaf of grain, a rosary, or a spinning wheel; as a goddess-figure whose body is conspicuously “carto-graphed” to approximate the geographical shape of India; or as a warrior goddess, often flanked by lions and armed with a sword or a trident, broadly approximating Durga. To be honest, in a country like India, such a diversity of artistic creativity and imagination is unsurprising. Tagore and Dwijendralal Ray, among others, embraced robust imaginings of the nation as mother, shot through with tropes of power and quite different from the ascetic iconography of Abanindranath.

In short, there is nothing wrong with stylised, power-laden imagery of the Bharat Mata being preferred by artists, citizens, politicians and others as long as they are not used as symbolic gestures seemingly acting as subtle forms of ideological signalling. This is where the problem in Kerala lies — in the alleged insertion of a ‘non-official’ symbol of religious nationalism in a constitutional office that’s traditionally apolitical and ceremonial. Since Bharat Mata isn’t a recognised symbol like, say, the Ashokan Lion Capital, her very specific visual representation becomes a problematic element in government functions. Thus, the stakes in Kerala’s battle over Bharat Mata run deeper than protest logistics. Indeed, by turning the symbol into a litmus test for how India defines patriotism and secularism in public culture, they touch the heart of India’s federal, secular democracy.

Now to the last of this triptych, Jai Shri Ram, which has its roots in Bhakti traditions, especially those venerating Rama as an avatar of Vishnu and the embodiment of dharma. In devotional communities, particularly those influenced by Tulsidas, chanting Rama’s name was a spiritual practice emphasising ethical living. Common greetings like Sita-Ram, Ram Ram, Jai Ramji ki, and Jai Siya Ram have traditionally signified humility and devotion.

But the more assertive Jai Shri Ram was less frequently used in daily parlance until the late 20th century. In its evolution from a devotional chant to its current location at the interstices of faith, nationalism, and identity politics, Ramanand Sagar’s television adaptation of the Ramayan (1987-88) was a major catalyst, turning religious mythology into popular culture. In the decades since, Jai Shri Ram has become a potent tool of political mobilisation and a focal point of a mythic-nationalist narrative, particularly associated with the rise of Hindutva ideology. It was during the Ram Janmabhoomi movement, spearheaded by the Vishwa Hindu Parishad and supported by the Bharatiya Janata Party, that it became a political battle cry. It was among the slogans shouted by the crowd during the demolition of the Babri masjid in December 1992 which indelibly changed its meaning and made it a symbol of militant assertion. Its public and performative use in recent years continues to be associated with assertion rather than prayer, involving, for instance, coercive chanting during incidents of mob violence and communal tension, notably during the riots in northeastern Delhi in 2020. It has also become quite normal for self-appointed gau rakshaks to force Muslim cattle transporters to chant this while assaulting them violently, even murderously.

The use of this slogan to provoke or polarise communities, especially in communally sensitive areas, has also been seen in recent years in the BJP’s carefully orchestrated Ram Navami processions in Bengal. In a strategic twist in the tale of its polarising power, Trinamool Congress workers, too, chanted a throwback variant of the slogan — the milder Jai Siya Ram — during the Ram Navami celebrations in the state in 2025, thereby trying to reclaim the religious space from the BJP by blending devotion with a carefully-crafted political message of communal harmony. Clearly, political calculations in democratic India create intriguing, and often counterintuitive, dynamics of exclusion, polarisation, reclamation, appropriation, and reappropriation, especially over competing symbols that lay claim over the nation’s ‘soul’.

As our 79th Independence Day approaches, it bears remembering that the Indian nation, in the capaciousness of its ideas and imaginations, is far greater than the fundamentalist and parochialising distortions foisted upon the nation’s pluralist imaginations by majoritarian muscle-flexing. The Constitution’s Article 1 does baptise the country as ‘India’ and ‘Bharat’ — a duality and a compromise arising out of the Constituent Assembly debates during 1946-50 about competing ideas of India. But Bharat is not equal and analogous to Bharat Mata, which has a fraught history of visual iconisation. So let’s not stray beyond what the Constitution has given us. And let’s not segregate Ram and Sita, whom we love as a couple, notwithstanding the tribulations Sita had to go through. At this moment of our history, we need prudent patriots, not provocateurs and persecutors.

Jayanta Sengupta is Director, Alipore Museum; jsengupt@gmail.com