In 1990, Federico Faggin, the inventor of the microprocessor, was lying in bed near Lake Tahoe on a family vacation. A successful businessman and a scientist by all conventional metrics, Fagini nonetheless felt like he was “dying inside”, unhappy and discontent. Unable to fall asleep, without warning, his chest exploded with a beam of energy. A “white, scintillating energy… fifty thousand times stronger than anything”, he felt, flowed from somewhere within him, an energy that was filled with “love, joy and peace”. This energy and his own consciousness expanded to “everything” and Fagini proclaimed: “I am that.”

Three decades of research later, in 2024, he expounded upon his mystical vacation in Irreducible: Consciousness, Life, Computers, and Human Nature. In it, Fagini answers the age-old, ‘hard problem of consciousness’ query: how does first-person conscious experience arise in a world made up of insentient and inert matter? Does consciousness emerge from the world or create it? Going against the grain of scientific consensus, Fagini argues that life cannot be reduced to the biochemical processes of the brain. Rather, the true nature of reality is a “quantum phenomenon”, namely consciousness, and the world described by classical physics is an evocative “symbolic representation” of this deeper reality. This alignment of science and spirituality is striking. One could be forgiven for mistaking Fagini’s conclusions for the famous mahavakyas of the Upanishadic seers — aham brahmasmi (I am that) and prajnanam brahma (brahman is consciousness) — that claimed a deeper, abiding, spiritual reality behind the world of physical appearances. But Fagini’s work is not yet another tiresome attempt to coerce a friendship between science and spirituality. Something deeper is afoot that deserves our attention.

We are in the nascent stages of what Thomas Kuhn famously called a “paradigm shift” in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions: when “normal science” is thrown into a state of crisis and calls for “extraordinary research” to debate fundamentals. Fagini’s work represents an emerging trend — exhibited, for example, in the works of David Chalmers, Christof Koch, Giulio Tononi and Swami Medhananda, to name a few scholars — that is placing pressure on both mainstream science and popular faith to justify their claims to truth. The paradigm of physicalism in science — that electrical and biochemical signals in the brain are the foundations of our sense of self — is now increasingly criticised as reductive. Conversely, the paradigm of faith in non-material states of existence that characterises popular religion — that entities like the immortal soul and god are real — has long been characterised as pseudo-scientific and superstitious for its inability to provide hard evidence in support of its claims. As a result, for every claim of what Vivekananda called “religious popery” — an appeal to authority when religion is unable to convince us through logic and reason — we have a claim to ‘scientific popery’ — where the possibility of spiritual truths is ruled out ab initio as a scientific article of faith. Fagini represents a dual criticism of both tendencies in search of new foundations for a unified theory of reality.

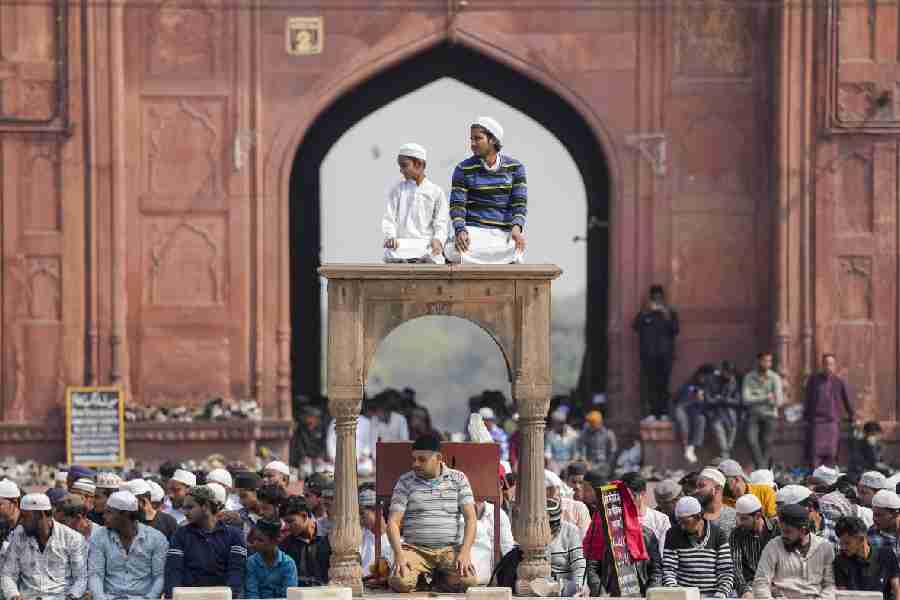

This debate has deep cultural implications. Historically, it was predicted that the rise of science would sound the death knell for religion. This so-called secularisation thesis has not played out. Religious forms of life have demonstrated an unabated vitality over the last century in India and around the world. They now co-exist with the universal cultural purchase of the scientific outlook that characterises modern societies. This co-existence, however, is far from happy. Believers often take the slightest hint of the scientific failure to answer deep questions as a sanction to slip in the whole gamut of fantastical theological claims. Conversely, many on the scientific side unjustly refuse to admit that the scientific method of physical experimentation and observation does not exhaust all ways of knowing. Even outside these extremes, history attests to the innumerable and unhappy compromises between these two antagonists. Eager to prove compatibility, we cleave the world into two halves: science explains the physical world and religion concerns questions of meaning and value. After all, most people, scientists and believers, find no problem in navigating daily life with this dual allegiance.

The problem is that each of these approaches is procrustean. They avoid questions that do not succumb to easy explanation from within our established world view, scientific or religious, or, at most, rest satisfied with superficial claims of compatibility. Psychological comfort takes precedence over truth. As a result, studies like Fagini’s that attempt a deeper reconciliation between science and spirituality are co-opted by either side to claim victory for their camps. These developments, however, are neither a bargaining chip for believers to say ‘I told you so’, less still to artificially inflate cultural pride, nor for the scientifically-minded to roll their eyes. They are an invitation to explore, whether we start from the religious or the scientific end of things.

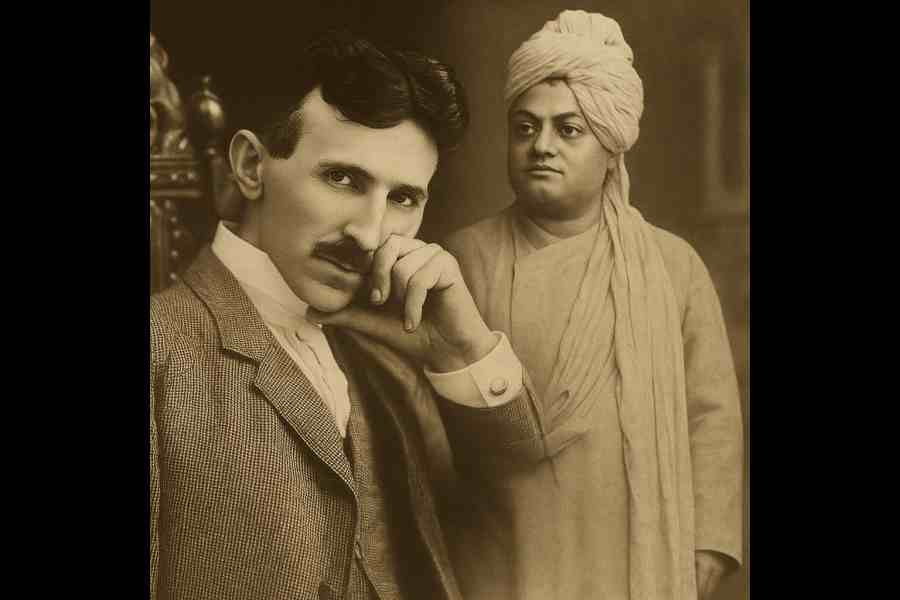

This orientation has a particular salience in India. Over a hundred years ago, spiritual figures like Vivekananda and Aurobindo engaged in a philosophically robust debate with scientists like Nikola Tesla, Lord Kelvin, Albert Einstein, and J.C. Bose. In doing so, they criticised the orthodox pundit for his religious superstition and inertia as pungently as they chastised the self-confident forays of science into spiritual domains beyond their competence. What resulted in the early-20th century, therefore, was a spiritually sensitive and analytically rigorous debate that took seriously both the mystic core of Indian spiritual heritage and the exciting developments in fundamental science to develop a unified theory of reality.

Unfortunately, we have since lost that exploratory urge. Amidst the intellectually bankrupt and inane culture wars — debating whether Ganesha had plastic surgery or Karna was the child of genetic engineering — serious research suffers. Ideological rifts colour philosophical work. Proponents either uncritically affirm or deny the validity of India’s spiritual knowledge systems. It is time that the spirit of science meets the science of spirit. As the cutting edge of science in Western academic institutions is now beginning to take spiritual ideals embodied in Indian traditions seriously, it is time that we started taking our own ideas seriously. The implications of this research agenda are far-reaching. It includes, for example, neuroscientific explorations of the brain-mind interaction, the conversation between quantum physics and consciousness studies, the relationship between allopathic and traditional medicine, and the interface between academic psychology and yoga.

This vision of research requires a supportive financial, intellectual and cultural atmosphere that is rare in India. The fortunes of departments of Indian philosophy in our universities have been declining, as much as those dedicated to basic scientific research. The recent institution of research grants by the Indian Knowledge Systems Division in the ministry of education is a welcome, if small, step in the right direction. The National Education Policy similarly calls for renewed attention to the “rich heritage of ancient and eternal Indian knowledge”. What we need now is a concerted attempt across government, academia and private donors to bring our spiritual knowledge systems into the 21st century.

Raag Yadava is a lawyer and an academic