We take the eyes for granted. And so too, the hand.

I write today about the hand by which I mean, basically, the palm, its flat midland which hosts lines criss-crossing into what some believe are the plans the fates have made for us. And I mean, too, the five digits we call our fingers and thumb.

Losing one’s sight, or even its dimming, can be about the greatest challenge in life. Losing the use of one’s hands, by neurological or any other cause, is, similarly, a great adversity which has to be overcome. Seeing a hand so affected has been for me a lesson in self-reliance and self-respect.

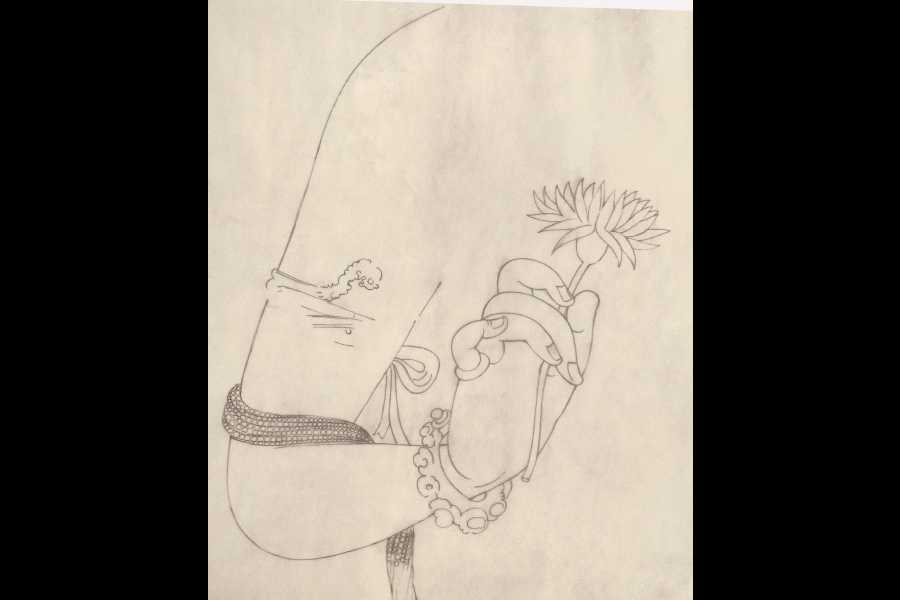

My preoccupation with the hand started with seeing, when I was a child, pictures of Auguste Rodin’s sculpture, famously and simply described as The Hand. It spoke as no words can. And, following that, I have never failed to notice hands in art, as in depictions of the Buddha, of the abhayamudra, the Avalokitesvara painting in Ajanta.

The Indian and South Asian ‘namaskar’ and ‘aadaab’ are about the most beautiful choreographies of human creativity. One can do either in a myriad ways (picture these as you read): perfunctory, patronising, formal, ceremonial, respectful, reverential, trusting, casual, even cunning, cynical. I could go on. But just see, if you can, on any of the many electronic platforms available, the namaskar being offered like a tray of flowers by Gandhi to Rabindranath Tagore at Santiniketan when the Gurudeva was receiving the guest he called ‘Mahatma’ and his wife. Or see the namaskar that Nehru offers (as prime minister, incidentally) to Vinoba Bhave. The namaskar that was exchanged between President K.R. Narayanan and M.S. Subbulakshmi after the ‘Nightingale of India’ was conferred the Bharat Ratna by the then head of State is a sight for the gods. It has gratitude and respect, gladness and fulfilment, but shown by whom to whom? As much by the giver as by the receiver of the decoration.

If anything can distract my attention from their music, it is the way the hands of Pandit Ravi Shankar and Ustad Vilayat Khan move on the strings of their sitar, the fingers of Pandit Shiv Sharma and his son, Rahul, on the santoor, the manner in which the wrists of Vikku Vinayakram produce elemental rhythms from his ghatam, and Ustad Alla Rakha on the tabla.

While hearing Ustad Bismillah Khan playing his shehnai, one has to close one’s eyes to the mundane world. That is natural. But that also elides a scene made by the heavens. The way that genius held the instrument, the delicacy with which his fingertips moved on its finger holes, are a lesson in humility and respect apart from sheer mastery. Balasaraswati’s bharatanatya abhinaya is legendary because of her use of her eyes and, equally, her hands. In her dance, they are not limbs but language.

Few photographs have affected me as much as the sublime one of a child on someone’s shoulder surrounded by the helmets of soldiers in Tiananmen Square, Beijing, 1989. His gesture has in it fearlessness and faith but also — and this is where it is sublime — a compassion for the soldiers who are obeying mortal orders. There is a similarly affecting photograph of children in Lucknow doing an aadaab — utterly beautiful for the ease of their gesture’s grace, the laughter in their eyes, the sense of togetherness in their hands.

Snake charmers and snake-shows are a no-no now but the way the sapera held the been or pungi was something to behold, likewise the élan with which the dhunki wielded his single-string instrument to card or fluff quilts, the bhishti to squirt water from his leather-skin mashaqs. And, of course, the potter! Her or his hands shaping the whirling clay from dollop to living sculpture over the wheel, moving from round to oval or squat or slender with a neck lovelier than a swan’s or that of a gazelle, is to see Creation. But no less, yes, no less — and anti-tobacco-ists will bear with me — I have watched with conflicted emotions the making of beedis in West Bengal’s Murshidabad by slender female fingers, paring the leaf, filling them with its contents, folding them just so, tying them with a string, turning the two ends into neat flaps, and completing the task with deference to exact and exacting specifications. Seeing them at work, I have said, ‘Bless your labour, curse its abuser.’ There was a time when I admired the deft stroke with which a smoker lit his matchstick in one swift motion, turned it face down to keep the ignition alive, and touch it to his cigarette end with the kiss of poisonous infatuation.

The finger’s tip is meant to touch; its knuckles to knock. But the digits’ use to send an arrow into the air is something one has to see Mithun Chakraborty do in Mrinal Sen’s Mrigayaa. Mrinalbabu once explained that he got a tribal to teach Mithun how to do that: “Don’t hold the arrow as you would a gun and its trigger. Your knuckles must grip the reed tight and then let go…” The actor does this to perfection.

Hand gestures of the great are a fascination. An iconic photograph of Sri Ramakrishnadeb, with his right hand raised with fingers held in an extraordinary arrangement, as if holding the globe, is impossible to define. The philosopher, Ramchandra Gandhi, once described that as the master’s spiritual googly sent to a confused bat-wielding world. I do not know if Babasaheb Ambedkar used his arm in the way his statues show him do but that upraised arm with forefinger making a point is needed, politically and ideologically.

If any gesture has gone into the cellars of infamy, it is the Nazi salute. Any politician using it ignites emotions that are best left undescribed. I must say here that I find the gesture said to have originated in Hitler’s counterpoint, by Winston Churchill — the ‘Victorius V’ — to be arrogant and conceited apart from being singularly unaesthetic. Can you imagine Lincoln, Tolstoy, Gandhi or Mother Teresa holding up their forefinger and middle finger to celebrate personal success?

Fingers are also used with telling effect, in cheap gesticulations. I need not elaborate and will conclude with something that goes with fingers, the ring.

On slender or gentle fingers, a single ring can look beautiful. When it betokens marital status, it instils respect if also, to the romantically ambitious, the ‘message’: ‘I am not available.’ But a multiplicity of rings that does not leave out even the thumb is an altogether different form of adornment. Simple fear and simpler faith in the ‘power’ of gemstones to ward off the evil eye drive this form of ornamentation. I cannot begrudge that. Fear is normal, fearlessness rare. But I cannot overlook the fact that if the fingers of the members of the Constituent Assembly or even of the first two or three Lok Sabhas were to be seen, the majority of them would be ring-less or single-ringed.

Kerala is the home of the greatest use of fingers for saying what words fail to. Contempt would be shown by a gesture that seems to flick off cooked rice grains stuck on the fingertips. Duplicity, by a plaiting of the forefinger and the middle finger which are then moved in cork-screw coils. And an inquisitorial questioning by fist closed and thumb held up to the skies asking, ‘What?’

“Thy Hand, Great Anarch” is the title of the 1987 autobiographical work of the polymath, Nirad C. Chaudhuri. Alexander Pope’s The Dunciad, its original, says:

“Thy hand, great Anarch! lets the curtain fall;

And universal Darkness buries All.”

I would like to adapt that to:

My Hand, great Anarch! says it all

And makes me stand head up or fall.