In an ideal world, the outcome of the election to the Delhi assembly would have merited just a casual footnote in the national mindscape. Although there is an undeniable importance that is accorded to a national capital, this does not normally extend to its local administration. In terms of population, Delhi is more than Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand but somewhat closer to Haryana. However, while these territories were granted full statehood, Delhi’s statehood has always been qualified. Its elected government, located in the Old Secretariat complex of the Civil Lines, does not control law and order in the entire territory and is also spared the responsibility of administering the civic infrastructure of the exclusive zone popularly known as Lutyens’ Delhi.

In political terms, there has often (but not always) been a mismatch between the way Delhi has voted in parliamentary elections and the choices it has exercised for the 70-member assembly. Those with long memories may recall that the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, the earlier incarnation of the Bharatiya Janata Party, surprised everyone by winning six of the seven Lok Sabha seats in 1967. This was a source of great irritation to Indira Gandhi who relied on what one commentator called “busloads of arguments” in her battle against the Congress old guard in 1969. Having wrested back the lost seats in 1971, the local bigwigs of Delhi played a seminal role in unleashing the tyranny of the Emergency. Many of them subsequently earned notoriety by leading the mobs during the anti-Sikh riots of 1984.

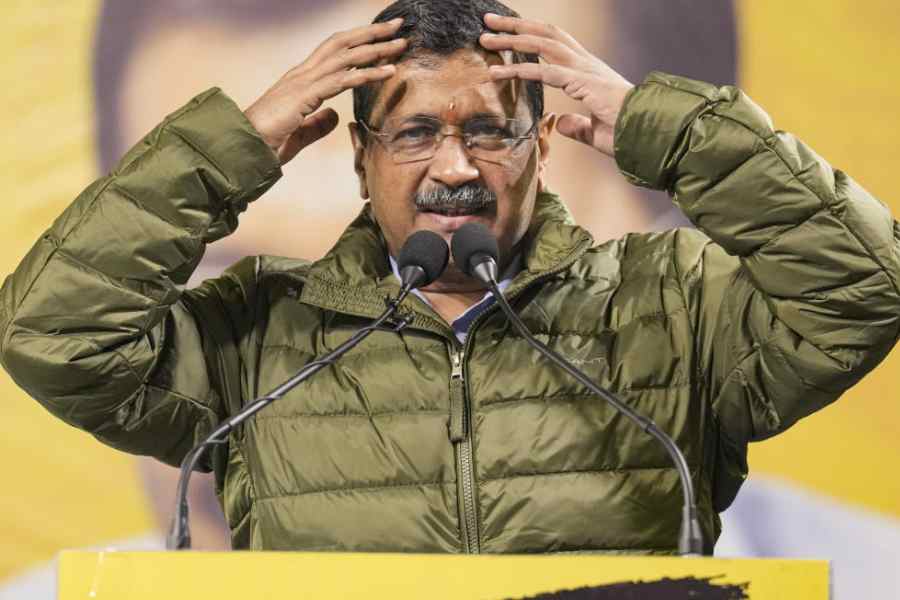

The see-saw competition between the Congress and the BJP was disrupted in 2013 when, following Anna Hazare’s India Against Corruption agitation, the Congress was eclipsed by the newly-formed Aam Aadmi Party. With the avowed aim of disrupting the status quo and heralding a new politics, Arvind Kejriwal and his core team of activists drawn from non-governmental organisations swept the Delhi assembly election in 2015. The AAP’s success lay in securing the near-total allegiance of the Congress’s support base among Muslims and slum dwellers. This was complemented by a significant slice of middle-class votes from people who in a parliamentary election voted either for the BJP or the Congress. The AAP was particularly successful in ensuring that the euphoria around Narendra Modi remained confined to national elections and didn’t percolate down to municipal politics.

Although the AAP made its debut with the lofty claim of providing a national alternative to both the Congress and the BJP, this was never realised in practice. In the 2014 Lok Sabha election, the AAP put up star candidates all over the country, not least in Varanasi where Kejriwal took on Modi. It drew on the involvement of thousands of volunteers — a disproportionate number of whom were drawn from NGOs — who combined dedication and enthusiasm with virtue signalling. It is understood that crowdfunding, including sizable contributions from overseas Indians, played a big role in bankrolling the AAP’s candidates. Additionally, some of India’s big media houses extended their support to the start-up party as did a large section of academia.

The AAP’s national pretensions were punctured in 2014. However, rather than spread itself too thinly on the ground, Kejriwal wisely chose to focus on Delhi and Punjab. With the 2015 victory in Delhi, the AAP also managed to forge its own ecosystem based on the popular desire to try something different. With the patronage powers of the Delhi government at its disposal, the AAP was able to create an incremental support base among two professional groups: academics and journalists. There was always an overlap between academia’s endorsement of the AAP and its support for the Congress, other regional parties and the rump Left. It was academia’s divided allegiance to different anti-BJP forces that was a factor in pushing the AAP in the direction of the Congress-led INDIA combine. It was an association that neither the Congress nor the AAP was entirely happy with. This incoherence showed up in the 2024 Lok Sabha election when, despite a seat-sharing arrangement, neither the Congress nor the AAP was able to counter the BJP in any of the seven parliamentary seats of Delhi.

The support it derived from media houses and journalists was another big factor in propping up the AAP. Whether it was an exasperation with the media-unfriendly orientation of the Modi government or the lavish media plans of the governments of Delhi and Punjab that generated goodwill for the AAP is a matter of conjecture. However, there is no doubt that the extravagant expenditure on the infamous 'Sheesh Mahal' built for the chief minister was consciously underplayed in the media. This was understandable because, as the election outcome revealed, it was this issue that destroyed the moral halo around the AAP.

During the election campaign, it was also made out that the goodwill for the AAP’s 10-year rule arose from its sensitive handling of school education and its primary healthcare programme centred on mohalla clinics. While the political returns from creating a network of good schools are never instant, there were expectations that the supposed goodwill for the mohalla clinics would witness instant returns. However, anecdotal evidence during the campaign suggested that a very large number of these clinics were non-functional. The reason this didn’t create a bigger splash was the AAP’s special relationship with the media and the marketing of its ‘alternative’ model by academics.

The AAP’s Delhi defeat has dented the intellectual arrogance of the ‘alternative politics’ practitioners who bedded with mainstream anti-BJP parties in the INDIA coalition and yet maintained a contrived distance. The post-poll justification by AAP-supporting intellectuals that the BJP successfully shifted the centre of gravity to the middle classes is a comforting message to the defeated party. However, the Lokniti-CSDS post-poll analysis of the Delhi election shows that the erosion of the AAP from 61% (in 2020) to 50% among the poor, and from 62% to 44% among the lower classes was more substantial than its decline from 53% to 44% among the middle classes. In short, it was the failure to deliver a decent quality of governance that was at the root of the AAP’s failure to win a third term.

It is, however, also clear that the AAP’s core vote among the poor remains intact and that it would be a folly to dismiss its political relevance on the strength of one major defeat. Its future will depend substantially on how much success the BJP makes of its newest addition to the double engine fleet.