One of the ennobling gifts of literature is the light it shines on our essential condition beyond the frontiers of time or context or geography; it’s a thing of undying

luminescence.

For a while now, I have been trying to get a sense — in a most scattered way, and in a way that often appears like walking on shattered glass that defies becoming what it once was and refuses a clear view — of what might be happening all around us and why on earth?

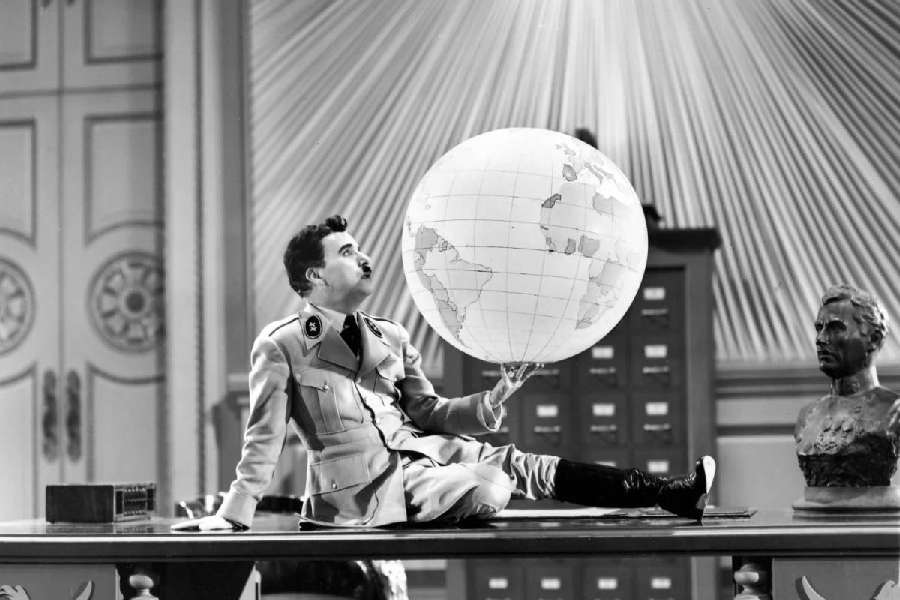

We are in a convulsed space; it cannot be that we are not shaken by it, so violently shaken and bewildered that it becomes difficult to make sense of the running reel of our times, at once unbroken and fractured, often like the most bizarre, even hallucinogenic, vaudeville. Elon Musk unleashes the Nazi arm from a public platform in a rhapsodic act of celebration. So does Steve Bannon, Musk’s bitterly opposite number on the ruling bandwagon of the United States of America. Their common boss, President Donald Trump, is bromancing Benjamin Netanyahu and is not a whit embarrassed about posting dystopian dreams of a Gaza cleansed of what remains of its ravaged souls and transformed with a swish of the djinn’s wand — Aladdin’s djinn, surely, who else’s would be closer at hand? — into a luxe resort swilling cocktails on the beach. Where’s the sense in all or any of this? Or is it no longer a thing for things to make sense? Have these men, these who are possessed with, and threaten, the most awesome buttons of power no notion of how their actions filter through the ‘never again’ lessons of Kristallnacht and the horrors that were brought to bear in its wake? Their demeanour could range anywhere from the clownish to the roguish, or, most possibly, a diabolical alchemy of the two. They almost seem at play with the devastations they are triggering around them. It recalls the satire of Charlie Chaplin at play with the globe. It’s no less than astonishing what we learn and choose not to. Never again? We seem to profess and practise quite the opposite: never say never again.

I came upon, in my near-disoriented search for some manner of explanation of why things are just how they are, a Saul Bellow volume called To Jerusalem And Back. It is a slip of a book from the mid-1970s and, as its title suggests, a travelogue, though not an ordinary one because it is the account of a deeply learned and constantly learning man. Buried in its fascinating layers lay an oracular passage that had little really to do with a journey to Israel but far more about who we — humans — may also be. So here goes, a literary man shining the torch on us held in the hands of a predecessor — Fyodor Dostoevsky. The context is Dostoevsky’s The House of the Dead and crime and murder, both inseparably woven into human nature. “Dostoevski [Bellow’s spelling], no mean judge of such matters, thought there was much to be said for the murderer’s point of view,” Bellow writes, “Navrozov [the Russian writer, Lev Navrozov] extends the position. Liberal democracy is as brief as a bubble. Now and then history treats us to an interval of freedom and civilisation and we make much of it. We forget, he seems to think, that as a species we are generally close to the ‘state of nature’, as Thomas Hobbes described it — a nasty brutish, pitiless condition in which men who are too fearful of death to give much thought to freedom.” As I was reading, I could not help thinking back to my Cairo assignment in 2011, the Tahrir Square protests and the eventual ouster of the Hosni Mubarak dictatorship. Seemed like a champagne moment, democracy uncorked. They called it the Arab Spring, and I wrote a piece in this newspaper on how I had read the underpinnings of the Tahrir revolt wrong, why I could not see the green shoots of democracy conquering new ground, not just in Egypt but across North Africa, from the Maghreb to the Horn — an almost ecstatic letter of

apology to the reader that also doubled up as celebration for the banishment of a brutal dictatorship. And yet, what has come to transpire in Egypt since? Dictatorship redux. My dim reporter’s eye on the prospects of democracy in the Arab world had probably seen right. Some would say Egypt had been restored to the prophecy of Hobbes, or the truth of Navrozov’s perception.

Are we in that moment, in the belly of a bubble that has burst and taken ‘liberal democracy’ along, kicking and screaming, or perhaps not? Are we living the Hobbesian description? Have we, or have we not, become subjects of a global confederacy of autocrats, some of them elected, some unbothered about where their mandate to wanton acts may even have come from? Is there not, raging all around us, the spectre of dictators masquerading as effigies of democracy, or, as happens, even its venerable mother? Have democratic mandates not been twisted into batons to beat democracy with? A comedian cracks a joke and the Establishment and its vandal vanguard come cracking after the artiste because democracy and its mummy have been defiled by a spell of satire. Democracy must also be what happens between elections; elections hand the winner the licence to authority, not authoritarianism. But between the largest democracy on earth and the most populous one, the standard operating practices are of a different nature — enshrine bigotries of race and religion and region, recast history to fashion a future of your fancy, threaten criticism, rebuff opposition and hold out the blade of retribution, dismantle institutions you don’t fancy, emaciate those that won’t do your bidding, exude fear not concord and confidence, be a bully, make bluster your leitmotif, act as if you are the bearer of heaven’s command possessed with divine mandate, not the transient mandate of the people. The jury’s out on who has understood democracy — as we know it, or likely don’t — and its uses better.

sankarshan.thakur@abp.in