Whatever one’s nationality — or religion — every sensible person should be relieved that a ceasefire has finally come to Gaza, that the remaining Israeli hostages have been released by Hamas, that the Israeli army and air force have (at least for now) halted their savage war, that food, medicines and other forms of relief can finally reach the beleaguered and brutalised Palestinians. But at the same time, every sensible person knows that this ceasefire is merely a very modest first step, and that the road to peace and justice remains arduous and tortuous, with many hurdles to overcome.

As it happens, in the weeks leading to the ceasefire, I have been reading two books, each of which contains some striking passages that bear on what could, or perhaps more accurately should, happen after the Gaza ceasefire. Both books were written in the early 1980s, and both have a very wide canvas, in which the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians is merely a sideshow. Yet what they said, even in passing, about this conflict forty and more years ago bears recalling today.

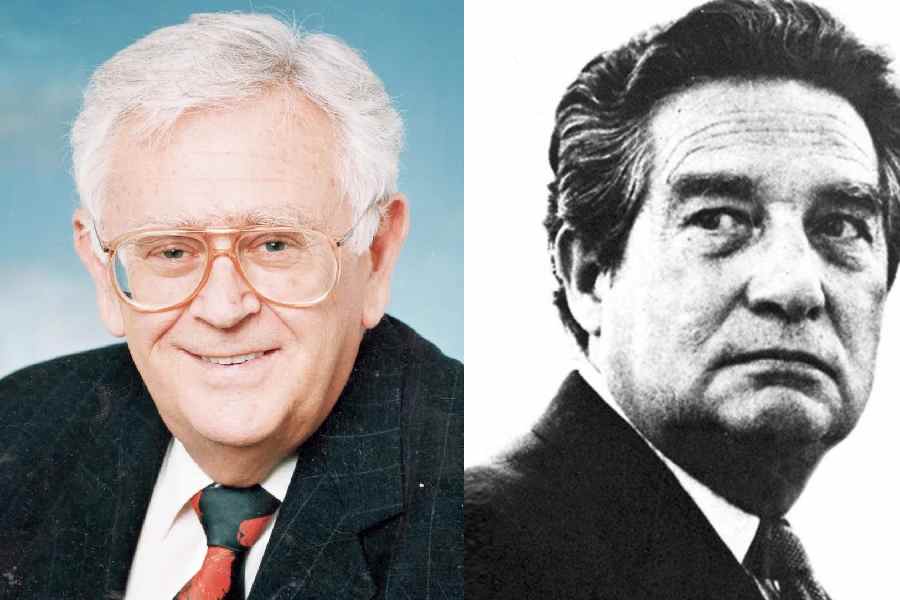

The first book is the autobiography of the celebrated South African freedom-fighter, Joe Slovo. Born in Lithuania, Slovo migrated with his family when the persecution of Jews intensified in Europe in the 1930s. They settled in Johannesburg, where Slovo lived on and off till the early 1960s, before going into exile. After the fall of apartheid, he returned to South Africa and served briefly as minister of housing in Nelson Mandela’s cabinet before dying of cancer.

Slovo’s book focuses chiefly on two things; his activism in the Communist Party and the broader anti-apartheid struggle, and the racist behaviour and punitive methods of the White South African regime. But before he comes to these matters, he tells us of how he served in Italy in the last phase of the Second World War. After the War ended, he spent a few further months in Europe before being demobilised. On his return to South Africa, he chose to stop in Palestine en route. As a Jew himself, he was curious to see a kibbutz in operation.

Of his visit to a commune near Tel Aviv in 1946, Slovo writes, “looked at in isolation, the kibbutz seemed to be the very epitome of socialist lifestyle. It was populated in the main by the idealistic sons and daughters of rich Jews who had amassed their fortunes in the Western metropolis. They were motivated by… the belief that by the mere exercise of will and humanism you can build socialism in one factory or one kibbutz….” That was the noble side of the experiment, but, as one looked closer, wrote Slovo, “the dominating doctrine on this kibbutz, as well as on the others, was the biblical injunction that the land of Palestine must be claimed and fought for by every Jew. And if this meant (as it did eventually mean) the uprooting and scattering of millions [of] people who had occupied this land for over 5,000 years, more’s the pity.”

In his memoir — written in the 1980s — Slovo looks back on the consequences of the victory of the ideology he saw at play in that kibbutz in the 1940s. He remarks: “Within a few years the wars of consolidation and expansion began. Ironically enough, the horrors of the Holocaust became the rationalization for the perpetuation of Zionist acts of genocide against the indigenous people of Palestine.”

The second book I have been reading, where Palestine figures briefly but tellingly, is a collection of essays by the great Mexican writer, Octavio Paz, a Nobel laureate in literature and incidentally also a former Mexican ambassador to India. The book is called One Earth, Four or Five Worlds: Reflections on Contemporary History. Published in 1983, it has essays on politics and culture in North and South America as well as in India. These are unfailingly insightful, as, indeed, are the essays on the Middle East.

The 1960s and 1970s had witnessed Palestinian guerrillas murder Israeli athletes and hijack Israeli planes. Paz disapproved of these acts of terror committed by the Palestine Liberation Organization and other groups fighting for Palestinian self-determination. As he acknowledged, “it is true that the Palestinian methods of fighting for [their] right have been, almost without exception, abominable; that their policy has been fanatical and intransigent.” He, however, added: “Yet, however grave all of this may have been and still is, it does not invalidate the legitimacy of their aspiration.” For, as Paz noted in the 1980s, “Israeli intransigence” was “the other side of the coin of the demagogy and fanaticism of the Palestinian leaders.”

Paz notes that “Jews and Arabs are branches of the same trunk.” He asks: “If they managed to coexist in the past, why are they killing one another now? In this terrible struggle, stubbornness has become suicidal blindness. None of the contenders can win a definitive victory or wipe out the enemy. Jews and Palestinians are doomed to live side by side.”

At the time that Paz was writing, few people were thinking about a possible two-state solution to the problem in Palestine. The Israelis showed no signs of giving up the territory they had annexed in 1967, whereas the PLO was in no mood to recognise that Israel, even within its pre-1967 borders, had any right to exist. Yet the Mexican writer could see that the uncompromising stand of both parties was immoral as well as unfeasible. He was clear that for what he termed this “terrible struggle”, the “solution cannot be military; it must be political, and founded on the one principle that will guarantee both peace and justice: the Palestinians, like the Jews, have the right to a homeland.”

A decade after Paz insisted that the only lasting solution to the conflict was for Palestinians and Jews each to have a homeland they could call their own, the PLO and the Israeli government signed what are known as the Oslo Accords. The PLO recognised Israel’s right to exist, while Israel acknowledged that Palestinians

needed their own state, to be constituted out of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

In the past thirty years, while Israel has gone — politically, economically, and territorially — from strength to strength, the Palestinians have seen the dream of statehood promised them by the Oslo Accords being nullified at every step. The murder of the peace-making Israeli prime minister, Yitzhak Rabin, by a Zionist terrorist was the first blow. Then came the steady expansion of Jewish colonies in the West Bank, built on Palestinian land usurped by settlers aided, encouraged, and supported by the Israeli army. The fact that the West Bank and Gaza were not contiguous was already a factor inhibiting statehood. The settlements have proved even more injurious, by turning the West Bank into two distinct zones, one of privileged and protected Jews and the other of harassed and persecuted Palestinians. The situation has prompted entirely legitimate comparisons to apartheid-era South Africa.

Joe Slovo’s reflections on the conflict between Jews and Palestinians were prescient; and, perhaps even more, those of Octavio Paz, likewise offered in the 1980s. Were Paz alive now, he would be the first to acknowledge that the methods of Hamas have been, if anything, even more fanatical and abominable than those of the Palestinian guerillas of the past; and yet he would nonetheless insist that they do not excuse or explain the brutal intransigence of the Israeli military, or invalidate the legitimacy of Palestinians to a nation of their own.

In the course of his book, Octavio Paz at one place remarks: “During World War II, André Breton wrote, ‘The world owes the Jewish people reparation.’ The moment I read them, I took these words to my heart. Forty years later I say: Israel owes the Palestinians reparation.”

Writing forty years later still, while endorsing Paz’s judgements, I would offer two amendments. First, after the Holocaust, it was not so much the world as a whole but the countries of Western and Eastern Europe in particular that owed the Jewish people reparation. Second, in the year 2025, it is even more clear that while Israel does indeed owe the Palestinians reparation, so do the countries that have supported Israel’s expansionist and colonialist policies — countries such as the United Kingdom, France, Germany and, above all, the United States of America.

ramachandraguha@yahoo.in