Each metropolis has its own particular soundscape and acoustics, as do different neighbourhoods within each city. In Berlin, the trams going through Potsdamer Platz between the spread out canyons of glass and steel sound very different from how they sound on the smaller roads around Ostkreuz; car tyres change their sound when shifting from plain tarmac to cobblestone; the parks and waterbodies give you summer birdsong, the small shouts of children, the putter of boat engines; everywhere, the trains of the S-Bahn and, sometimes, the underground U-Bahn maintain a metallic trundle-beat (that is very different to, say, the trains in the London Tube), and that also changes when it’s on a ground track or an overhead line. Walking — Berlin is one of the great cities for walking — through different neighbourhoods, you can map the transitions by how clearly you can hear the fizz of bicycle wheels, drowned out by cars, trains and trams or almost loud in a quiet, leafy, residential para.

Embedded within these ‘larger’ sounds are voices and music. Unlike many other western European or even German cities, Berliners are loud: they greet each other emphatically, they call out across crossings, the flinging of abuse and admonition between errant bikers and pedestrians around the bike lanes is unambiguous (though rarely does it seem to lead to physical altercation; this level of shouting in London would usually mean pushing, shoving and fisticuffs); they sometimes like to sing as they pass in groups; there is no concept of hushed speech except perhaps in the posh bars and restaurants.

Music adds to this aural universe in a variety of ways: someone quite skilled practises classical piano in a neighbouring apartment; in an arts centre recuperated from an old, decommissioned hospital, you move down the corridor accompanied first by beginner-level violin screech, then by advanced, free jazz tenor sax, followed by some Latin percussion practice; a car goes by blaring some sub-species of rap; the Döner shops play Lata-esque Turkish heartbreak; neighbours in the next row of buildings party late into the summer night, giving away their age with the soundtrack of classic 60s and 70s White Boy Blues, Allman Brothers, Ten Years After and Paul Butterfield/Mike Bloomfield; as you cross a street, you can hear some contemporary bhangra coming at you on a portable speaker and you know it’s one of the many young sardars who seem to have cornered the food delivery market (in Berlin, the Zomatiggy deliver on cycles rather than mopeds); outside the U-branch of the Warschauer Straße metro station, there is always a busker of some skill attracting a small crowd.

In one of those large apartments typical of the bourgeois areas, the living-room floor has been cleared. Guests get their drinks and scatter themselves on the floor, waiting for the musician to start. The man nods at everyone, speaks a few words, and picks up a string instrument that resembles a dotara. He starts to strum and pluck, waiting for the silence to coalesce around his notes. Then, almost as an afterthought, an undernote of humming joins the instrument, so soft at first that you think he’s added an invisible bass string. After a long while, the voice peels away, lifting off into the beautiful high notes of a song. There are three songs in an African language you don’t understand, each of them briefly introduced in English. The voice and strings rebound off the early-20th-century Berlin walls engulfing you in something magical. Just as you think he’s warming up, the musician from Guinea-Bissau stops and puts down the instrument. “Today, I’ll stop here because I don’t want to enter into deep prayer. On another day I can transport you to some special place but the time is not right today.” There is no thorn of ego in his words, nor a trace of any chastisement; just a statement of fact that he has gone as far as he is able to in the atmosphere of this particular gathering. I am sharply reminded of some of the great bauls I have been lucky enough to see and hear in similar intimate situations. I ask him the name of his instrument — it is called a ngoni.

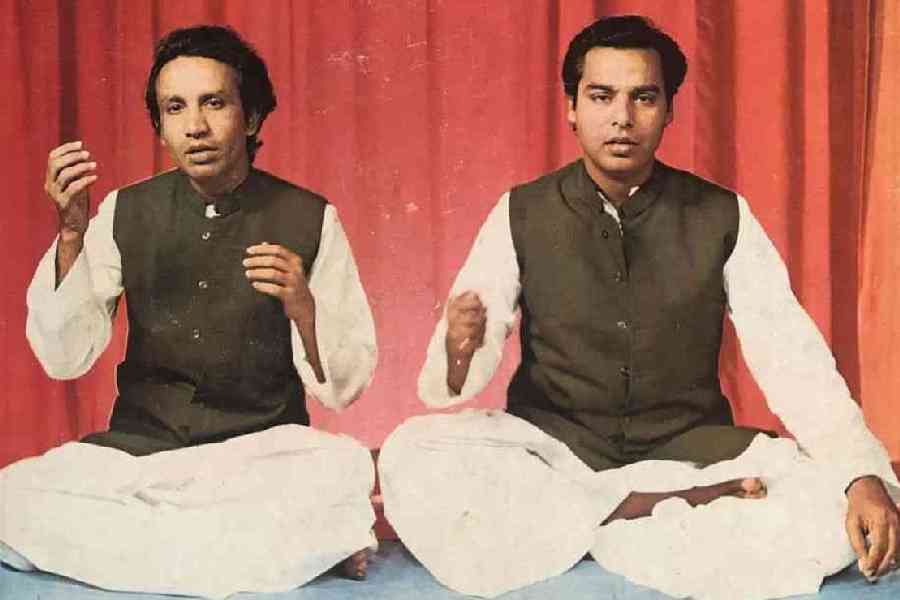

At the same gathering, I meet a French film-maker and film scholar who grew up in Berlin. “Do you know dhrupad music?” he asks me. I tell him I do, but how does he happen to know it? “We lived in an apartment building in the early 80s, in West Berlin, where the Dagar brothers were also staying. We could hear them practising and it was wonderful. My father was a musician and he made friends, so we attended some of their small concerts.” My eyes widen. “So, do you happen to have any recordings of those concerts?” He doesn’t, no, but after that he has been following dhrupad, catching live concerts in Germany whenever possible.

The street on which I’m staying is parenthesized by train tracks at either end. At the far end runs the S-Bahn and, closer to the apartment and its balconies, is a railway bridge that sees the regular passage of intercity trains heading to and from Warsaw and points east. The two track-lines produce quite different sounds but neither emits the howling whistle one associates with night trains. Across the road is a newly-constructed building, which looks like it’s some sort of housing for single mothers with children, except a few men also seem to be living there. Occasionally, the sound of a domestic quarrel breaks through the quiet and, twice a week, I can hear a women’s chorus practising songs in a language that sounds east European.

The other day, when dark clouds drew in to interrupt the hot spell, I remembered the Frenchman’s mention of dhrupad. I found the upload of an old recording on YouTube — the ‘Senior’ Dagar brothers singing Raga Megh. As the rain began to fall, dropping the temperature and creating an old-style European summer, I turned up the volume on the big house speakers so that the sound could go out onto the street. The alaap grew as the rain strengthened, two voices at first and, then, three, intertwining, tripping across each other playfully and precisely. While Delhi and Vermont flooded, while Greece and Sicily burned, I found myself on an island of perfect rain-music. In between the passages of singing, the ustad — I’m not sure which one of them — added spoken comments, but clearly for a home audience. After a particularly gorgeous long note, he interrupted — “Aur koi country mey aisi awaz nahi nikalti hai!” Sitting in this maze of sounds, I couldn’t help but think how right he was.