|

Kamal Kumar Mazumdar had once written that in Bengali book illustration there were two who opened our eyes — Gaganendranath Tagore and Dakshinaranjan Mitra Majumdar. The late Siddhartha Ghosh in his book on innovative craftsmanship and Bengali enterprise (Karigari Kalpana O Bangali Udyog) commented that perhaps the litterateur was not aware that the blocks of Gaganendranath’s remarkable paintings for Jivan Smriti by his uncle, Rabindranath, that slipped into the pictorial realm from realism, were made by another artist about whom Mazumdar himself had written: “The line drawings by a duo had won the hearts of both old and young. They are the father and son, Upendrakishore Raychaudhuri and Sukumar Raychaudhuri.” Incidentally, both were autodidacts.

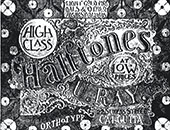

On his 150th birth anniversary, Upendrakishore (born May 10, 1863) is remembered more for his delightful writings for children and the evergreen entertainer, Sandesh, which celebrates its centenary this year, than his pioneering contribution to printing in India — introduction of half-tone blockmaking —which ushered in a new era of printing high-fidelity black-and-white and colour photographs, his artistic (he painted European style in oils, watercolours and pen and ink) and musical skills (he was a violinist and a composer, teacher and singer of Brahmasangeet), mastery of the art of photography, his satirical writing and experiments to reform Bengali typography. Even if he did not show any talent in so many fields, Upendrakishore would still be remembered for his contribution to process work (mass reproduction of photographs). In his own lifetime, a printing expert from abroad had commented that Upendrakishore’s contribution was far more original than that of his counterparts in Europe and America, “which is all the more surprising when we consider how far he is from hub-centres of process work”.

Upendrakishore’s forebears held the title of Deo and were from Bihar. They settled down in Chakdah, where their surname was transformed into Deb through acculturation. It underwent a few changes and finally became Roy. Upendrakishore’s biological father, Kalinath, was a Persian scholar. His original name was Kamadaranjan. But he was adopted by a childless neighbour, Harikishore, of Mymensingh, who renamed him Upendrakishore Raychaudhuri. He was always drawn to the philosophy of Brahmoism and he converted when he came for higher studies to Calcutta, first at Presidency college and Metropolitan College (now Vidyasagar College) thereafter, from where he graduated.

He changed his address several times, and before he constructed his landmark house at Garpar Road, he lived in rented quarters at 13 Cornwallis Street, where he got married to Bidhumukhi Debi, and where his three daughters and two sons were born. Upendrakishore started taking an interest in photography from college but it was probably in Cornwallis Street that he took it up as a profession. His house was equipped with a darkroom, and although few of his photographs have survived, many of them can still be seen in the pages of The Penrose Annual, a London-based review of graphic arts, printed annually almost without cease from 1895 to 1982.

Upendrakishore’s first significant book for children was Sekaler Katha, whose cover picture of a prehistoric creature with an elastic neck reaching out for a pterodactyl bore the initials U.R. The printing quality of his earlier book, Chheleder Ramayan, was poor as the wood engraver had ruined his illustrations, Siddhartha Ghosh wrote. After this unfortunate incident, Upendrakishore began to concentrate on half-tone as it did not cramp the style of artists, and the quality of illustrations did not depend on the engraver’s skill or lack thereof.

In 1910, Upendrakishore changed U. Ray, Artist to U. Ray & Sons and published his first book, Tuntunir Boi. At the time, half-tone was still a novelty, and once when Upendrakishore wanted to advertise his services in the print media, he was hauled up by a judge who was in the dark about it. Upendrakishore then pledged to spread the word.

One can get an idea of half-tone if one takes a close look at the paintings of pop artist, Roy Lichtenstein, composed of same-size Ben-Day dots. In half-tone, however, a screen (Upendrakishore had invented such a screen but never patented it) breaks up a photograph into an infinite number of microdots varying either in size, in shape or in spacing, thereby creating the illusion of continuous tone imagery. In the case of colour, a shade is reduced to the four primary printing colours — cyan, magenta, yellow and black (for depth), which are in turn, created by varying the intensity of the three light primaries — blue, green and red. By varying the density of the primary printing colours any shade can be reproduced. The dots of colour are not visible to the naked eye.

Half-tone was invented in 1873, and between 1897-1911, Upendrakishore had contributed nine research-oriented articles to The Penrose Annual, three of which are of significance — the theory of half-tone dot (1898), the 60 degree Crossline screen (1905-06) and Multiple Stops (1911-1912), says Diptendu Chowdhury, principal, Regional Institute of Printing Technology. Upendrakishore had patented the automatic screen adjustment indicator which printers had the option to buy along with Penrose equipment, as it made processing an automatic operation rather than one dependent on human intervention.

Upendrakishore’s son Sukumar in 1911 was trained at the London County Council School of Photo Engraving and Lithography and then at the University of Manchester. He was perhaps the first trained printing technologist in India. Chowdhury says that although half-tone is still widely used in the printing industry, in this age of digital printing the technique of screen distance has perhaps become obsolete. But it would have been impossible to reach the present stage without this stepping stone.