Cinema began its career in the early 20th century by borrowing heavily from the theatre. A hundred years later, can it still profitably do so?

Every scene in Aparna Sen's Arshinagar reminds the viewer that Shakespeare's universally circulated tale of the star-crossed lovers was written as theatre. Brilliantly innovative, Sen has combined the natural realism of the cinema with the staged dramatic narration of the theatre to produce a form never seen before in Bengali cinema. It begins with a puppeteer introducing Shakespeare's characters. The puppets then turn into real actors. The Montagues and Capulets of Verona become the Mitters and Khans of Arshinagar, locked in endless enmity. The two families, perfectly refined and sophisticated, make their money from land grabs, drug smuggling and other nefarious activities. Each family maintains an armed gang, led by the eldest son - Rono Mitter (Romeo) and Tayeb Khan (Tybalt). The audience, of course, knows the story, so the art must lie in the telling.

Unwilling to forgo the classical device of dramatic verse, Sen has her characters speak a rhymed verse that is contemporary and colloquial, generously mixing English and Hindi with its urbane Bengali. Zuleikha (Juliet), engrossed in her first mesmeric encounter with Romeo inside her bathroom and trying to ward off her nurse knocking on the door with a plaintive complaint in verse about "patla potty", is an absolute gem. The metre is open and unpredictable, and viewers can have a great time trying to anticipate the rhyme. This was a pleasure, one might add, of Calcutta's own urban performance culture of the kabigan and saung, lost for a long time but recently revived in new ways by the Bangla bands. Aparna Sen deserves enormous credit for introducing a speech form never used in modern Bengali cinema, except in Satyajit Ray's fantasy films.

But the most striking innovation in combining cinematic and theatrical forms lies in Sen's scenography. It takes a lot of gumption to use painted backdrops in present-day cinema, but she does it with aplomb. The Arshinagar slum where hoi polloi live is an obvious cinema set. The indoor scenes in the Mitter residence have bookshelves and cupboards painted on flat screens. Most astonishingly, a thoroughly realist rooftop scene in Lucknow is shot against a painted backdrop of domes and minarets, just as a fantasy scene of Romeo and Juliet on the seacoast in Bombay has painted high-rises. The combination of realist and non-realist modes is carried into the narrative style itself where thoroughly realist scenes of menace, intrigue, gang wars, arson and riots are interspersed with rousing music (by Debojyoti Mishra), choreographed dance and two Lalan songs by Parvathy Baul. Using several devices of modernist theatre - Bertolt Brecht comes most prominently to mind - Sen is able to craft an open cinematic style where there is no single privileged point of view. The song "Kala paisa wala", mixing biting sarcasm with righteous anger, is pure Brecht. On the realist side, Sen's depiction of a contemporary upper-class Bengali Muslim household is probably unparalleled in mainstream Tollywood cinema. In short, while grafting into her cinematic form numerous elements of modern theatrical narration, Sen is also able to fully utilize the visual power of today's high-definition cinematic projection, thus achieving a realistic tactility to which theatre can never aspire.

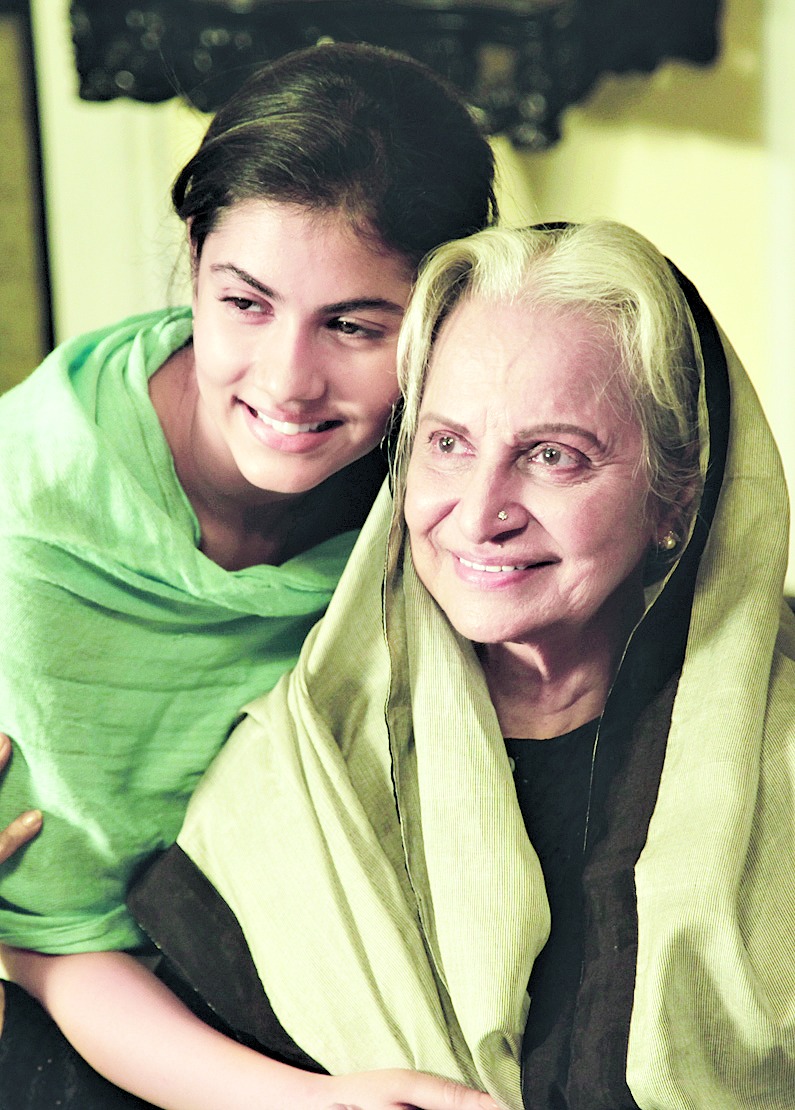

Of the superb cast, the Mitter and Khan gangsters stand out, probably because most of them are stage actors. In particular, Anirban Bhattacharya (Monte/Mercutio), Anindya Banerjee (Biloo/Benvolio) and Jishu Sengupta (Tayeb/Tybalt) are stellar. Rittika Sen is perfect as an innocent but adventurous Zuleikha/Juliet. One only wishes Dev was more convincing as Rono/Romeo. Kaushik Sen (Sabir Khan), Rupa Ganguly (Fufijan), Aparajita Adhya (Najma), Paran Bandyopadhyay (Mirza Saheb), Shankar Chakrabarty (Bishu Mitter) and Jaya Sil (Madhu) provide solid performances. Special mention must be made of Waheeda Rehman's superbly dignified Dadijan, the Khan matriarch. Finally, Swagata Mukherjee, the mischievous puppeteer-narrator doubling up as Zuleikha's devoted nurse, Fatima, is a revelation. The technical crew of Shirsha Roy (photography), Tanmoy Chakrabarty (art direction), Rabiranjan Maitra (editing), Debojyoti Mishra (music) and Priti Patel (dance direction) has ably executed the director's plan.

The idea of plotting a Romeo-Juliet love story along the Hindu-Muslim divide is not in itself particularly novel. Nor is Aparna Sen's invocation of the Sufi-Baul sensibility, highlighted by the film's title, which borrows from a famous song by Lalan Shah Fakir, unprecedented as the recommended antidote to communal hatred and violence. The sentiment will be endorsed by all sensible people. But it is particularly apposite for Shakespeare's play, because his tragedy of the young lovers represented a plea for putting an end to the bloody feuds and civil wars that marked the last phase of Europe's Middle Ages. Yet, it is not so much the message as the form in which it is delivered that marks Arshinagar as a landmark Bengali film. Formal innovation in commercial entertainment is always a risky business, since producers, actors and audience have deep stakes in the familiarity and comfort of settled conventions. But if no one is bold enough to break the form, how is the miasma of cloying sentimentality and nostalgia that currently hangs over Bengali cinema ever to be lifted? Everyone who wishes for a different future for cinema in West Bengal will congratulate Aparna Sen for her remarkably courageous achievement.

The writer is honorary professor, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta, and professor at Columbia University