|

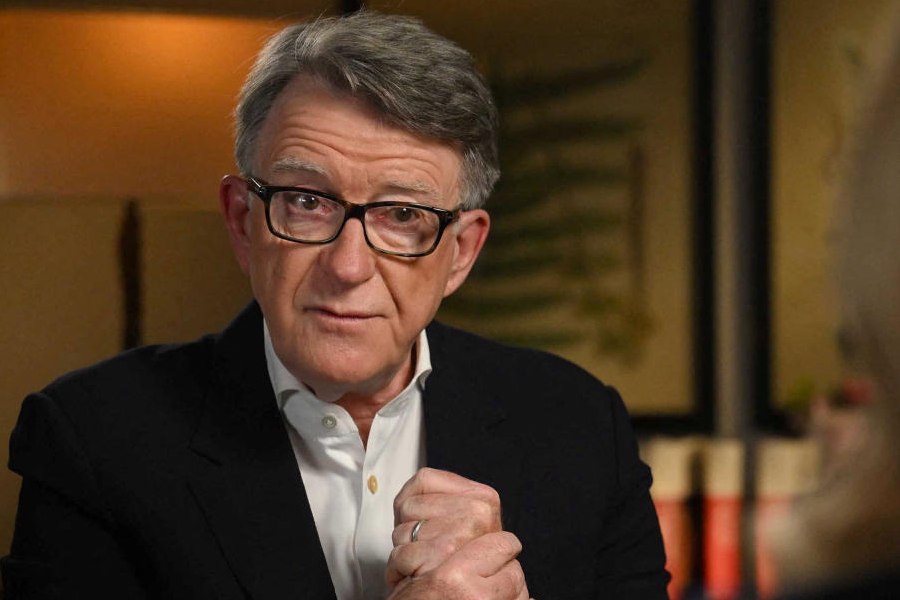

| Picture by S.H. Patgiri |

Rebati Mohan Dutta Choudhury

Rebati Mohan Dutta Choudhury is a feisty soul. Merry of spirit and still very young at heart. One of Assam’s pre-eminent litterateurs, he is also one of most loved and admired — for his clear-as-crystal honesty, soul-touching simplicity and down-to-earth expressions of quotidian life.

Of course, he is better known as Sheelabhadra, his nom de plume, of which he is extremely fond — essentially because Sheelabhadra, vice-chancellor of the ancient and renowned Nalanda University, was a “Colossus in the world of scholastics”. And for Dutta Choudhury, whose love for the pedagogic is boundless, Sheelabhadra was by far the “most perfect name by which to write”.

Now a sprightly 79-year-old, Sheelabhadra set sail into the world of literature mid-life. “I began writing at the age of 40 and even until a few days before I put pen to paper I did not have the whisper of an idea of this calling,” the writer says.

But thereon, his pen flowed intensely and incessantly to create some of the finest novels and short stories of Assamese literature — Madhupur and Tarangini, Agomonir Ghat, Anahatguri, Abichinna, Prachir, Godhuli and Anusandhan (all novels) and Bastab, Samudrateer, Tarua Kadam, Pratiksha, Uttaran, Mezaz, Sheelabhadrar Kuria Galpa, Nirbachita Galpa, Madhupurar Madhukar, Anya ek Madhupur, Uttar Nai, Dayitya aru Anyanya Galpa, Biswas aru Anyanya Galpa, Lagaria and several other collections of short stories.

His works have also been translated by the National Book Trust, the Sahitya Akademi and the Bharatiya Jnanpith into Hindi, Bengali, Punjabi, Telugu and Oriya.

Born in 1924 in Gauripur in Dhubri district, the author’s literary voyage began quite tempestuously, “goaded” by some thoughtless taunts that were thrown his way during his early years as a lecturer at the Assam Engineering College. “Stung by the many ridicules about my Bengali pronunciation, I resolved to prove that I was not apart from what is regarded as ‘Assamese’. And how better than by writing in the language?” Sheelabhadra asks.

His wordsmithy, peppered with the patois of his hometown, spun candid images of the world of men. They also captivated both lovers and critics of literature. The litterateur was honoured with the Sahitya Akademi award in 1994, the Assam Valley literary award in 2001, the Bharatiya Bhasa Parishad award in 1990 and the Assam Publication Board award the same year. But regardless of these distinguished recognitions, Sheelabhadra is diffident about “the measure of his success as a writer” — albeit he is content with having realised the challenge. “I have proved that Dhubri is a part of Assam’s literary map. It has assuaged my soul. But, frankly, I do not claim to be very original,” he says.

Sheelbhadra confesses that he has been influenced by Western authors, particularly John Steinbeck, Jean Paul Satre and Saul Bellow who remain his “favourite muses”. He says: “It is but natural then that Western idioms and writing style should have crept into my works too.”

It was very early on in life that Dutta Choudhury discovered the joy of books. In the well-equipped library of his father, he devoured the classics — both Western and those of Bengali literature. “One could say that was a preparatory period that later gave my pen the confidence to flow. After all, in order to be able to write, one must be acquainted with the literary trends of the world.”

Can then literature, commanding and conspicuous as it is, change society? Sheelabhadra dismisses it as “balderdash” and emphasises: “Any work that honestly reflects the hopes and aspirations of contemporary society can claim to have achieved a portion of success. Like Leo Tolstoy, for example, who though not a Marxist writer, could truly reflect the Russia of those times. Literature cannot metamorphose society.”

“Beloved teacher” Rebati Mohan Dutta Choudhury, however, built the essence of his life around imparting knowledge. He was, in his own words, “born to teach”.

“I found a strange contentment in teaching. And perhaps because I was so happy and fulfiled myself, my students enjoyed being in my classes,” he recalls with obvious pride.

A post-graduate in pure mathematics, first class with silver medal, from Calcutta University in 1946, Dutta Choudhury joined Cotton College as a lecturer for two years. Subsequently, after a nine-year hiatus from the teaching profession — during which he involved himself in the world of contracts and tea — he joined the Assam Engineering College in 1957, retiring from it as professor of mathematics in 1982.

Dutta Choudhury plunged into the “world of contracts” after his father’s death in 1949. His father, an affluent contractor, had left behind responsibilities which he had to shoulder to keep home and hearth together. “No doubt I earned money aplenty during those six years but I was not happy,” he says. So in 1955, he joined Assam Tribune as a sub-editor and then, “within a few months”, a tea estate as assistant manager.

Self-confessedly an “innate academic”, Dutta Choudhury is nonetheless gratified that he forayed into many other “worlds”. “Never have I regretted trying my hand at different jobs. On the contrary, each has been a learning experience, gifting me with the opportunity to break the shackles of typical middle class attitudes. Each world endowed me with insights into life, which I would otherwise have unfortunately missed.”

One such insight was gleaned from a moment in time during his years as a contractor, one he can still recollect vividly. “A labourer once asked for leave since his son was unwell. When he was back at work two days later, I asked him how his son was keeping. He did not reply. Quite offended, I asked the supervisor what was wrong with him. He then told me that the son had died.”

For the sensitive Dutta Choudhury, it was a moment of realisation, a moment when the truth of life merged into a single whole. “There was poverty of even grief in his life. A trivial incident perhaps, but one that held a wealth of meaning,” he says.

Sheelabhadra, master-narrator who was born of an expression of challenge, an outpouring of the heart, is true to his observations and experiences. Each novel or short story that he writes holds the reader in thrall — a patent of the flair of his powerful pen.