Recently, I was booking tickets for an upcoming trip to Assam, when suddenly, I got thinking. Now we have the facility to book tickets at the click of a mouse or the tap of a phone, and fly to destinations hundreds or thousands of kilometres away in just an hour or two thanks to air travel. But what about in the past? If we were to go back 150 or 200 years, and one had to travel to Assam or northeastern India, what did one do?

As always, I searched for answers in books and chanced upon a detailed account in Radha Raman Mitra’s iconic Kolikata Darpan (Vol. 1) and incredibly, part of the story linked to a man, long dead and buried, whose legacy lives on every day in the city.

Use of the inland river systems for traffic, mainly the Ganges-Yamuna-Brahmaputra system, only started becoming common in the 1800s, thanks to the East India Company’s growing footprints across the Subcontinent. With trade from Calcutta to London booming, there was a need for the fast movement of goods from the hinterland, and that in turn, necessitated focus on the internal riverine trade. By the end of the 18th century, the rivers of northern India were the primary means of transporting agricultural products to Calcutta port for export to Europe.

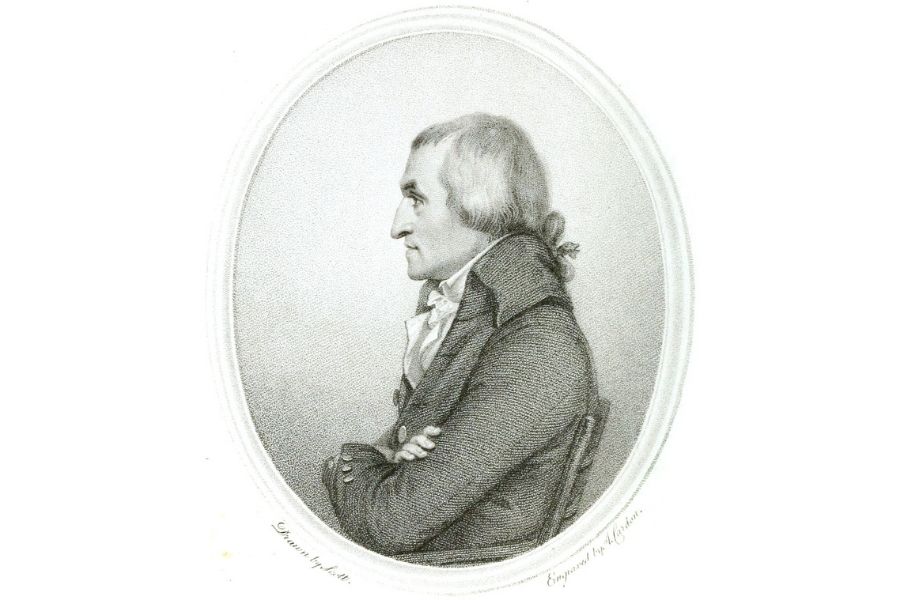

From the middle of the 18th century, a number of surveys were undertaken of the Gangetic network, starting with one by Surveyor-General James Rennell in 1764-65, followed by several more in the 1790s, most prominently the one conducted by Charles Reynolds in 1793.

From the middle of the 18th century, a number of surveys were undertaken of the Gangetic network, starting with one by (above) Surveyor-General James Rennell in 1764-65

In 1801 and 1807, Robert Hyde Colebrook, Rennell’s successor as surveyor-general, made surveys – first one up to Allahabad and the second one extending to Cawnpore (Kanpur). Colebrook’s findings and maps would serve as the baseline for a landmark survey conducted in 1828 by Captain Thomas Prinsep with the aim being checking the feasibility of steam-based navigation – a faster upgrade from the use of traditional boats and bajrahs.

Based on Captain Prinsep’s survey findings, a regular steam-based ship service was operational between Calcutta and Allahabad by 1834. In the rainy season, the 120-foot-long steamers went up the Bhagirathi-Hooghly, taking 20 days to reach Allahabad and eight days for the return. During the dry winter season, the steamers traveled through the Sunderbans with the Calcutta-Allahabad leg taking 24 days and the return 15 days.

In 1848, the East India Company established the first steamer service between Calcutta and Guwahati. This service helped connect Calcutta port with not only Assam but also several other important places in East Bengal like Dacca, Faridpur, Khulna, Chandapur etc. The government-provided service continued till 1860, when the Indian General Steam Navigation Company started steamer service between Calcutta and Assam valley in an understanding with the British administration. The steamers used to depart once every six weeks. The launch of the Sealdah-Kushtea rail service in 1862, however, marked a dramatic shift. A faster, safer and cheaper mode of transport was unveiled and would soon replace steamship-based navigation as the main mode of movement for both people and goods.

In 1848, the East India Company established the first steamer service between Calcutta and Guwahati (Representational image)

But before the introduction of steam ships, the connection between Calcutta, eastern Bengal and Assam was entirely dependent on large country-made boats. It took anywhere between six and eight weeks for a one-way journey, which was fraught with dangers. Boats from the east would arrive at Goalundo Ghat (presently in Rajbari district, Dhaka division, Bangladesh) and make the journey west from there via the Arial Khan, Harighata, Bhangor, Malancha, Raimangal, Hariyabhanga, Gosaba, Matla, Jamira and Saptamukhi rivers before making the final stretch through the Channel Creek (between Sagar Island and the mainland), before entering the Hooghly at a point roughly 70 kilometres south of Calcutta.

This long and winding route was physically draining for those making the trips and extremely risky in monsoons, when the rivers and channels were at bursting point. At this point, up stepped Major (later Colonel) William Tolly, an officer of the Company. Around the mid 1770s, he submitted a ground-breaking proposal to the Company administration. Tolly volunteered to dig up the silted old course of the Ganga that flowed past Kalighat, known as Adi Ganga, with the cost being met from his own pockets. The dug-up channel would create a shortcut connecting Calcutta port through the Sunderbans with eastern Bengal and onwards to Assam, cutting down travel time significantly.

Tolly dug up the silted old course of the Ganga that flowed past Kalighat, known as Adi Ganga, with the cost being met from his own pockets

The Company immediately jumped at the proposal, allowing Tolly to collect toll tax from boats plying on the channel after it was opened and also setting up a gunj, or market, on the banks of the channel at a suitable spot. Excavation on the old channel started sometime in 1775 and went on for over a year with the route opened up for riverine traffic in 1777. From the mouth of the Adi Ganga at Hastings, till eight miles eastwards up to Garia, the old channel was de-silted and deepened. From Garia, a new course was dug for nine miles till Shamukpota where the channel connected to the mighty Bidyadhari. The 17-mile stretch from Hastings till Shamukpota came to be known as Tolly’s Nullah.

The boats from Calcutta could now sail eastwards via Tolly’s Nullah, arriving at the Bidyadhari and eventually on the Matla and finally, the Kalindi, which took the boats to Basantapur of Khulna district, which in turn was connected to Barisal by waterways. The 187-mile journey from Calcutta to Barisal was cut down by 60 miles thanks to Major Tolly’s efforts.

The market that he set up south of Bhowanipore area also bore his name – today’s Tollygunge. When Sir William Cruikshank established a club to promote all kinds of sports in the vicinity, it also took the same name – Tollygunge Club.

Goalundo Ghat in Faridpur, Bangladesh

Incidentally, since a Bengali and food hardly ever remain separated, it would be good to end this tale of a famous food that originated somewhere over the riverine network spanning the two Bengals. Goalundo Ghat was a kind of mid-way spot, where the mighty Padma (main Gangetic channel) met the equally impressive Meghna (Brahmaputra).

Much later, in the late nineteenth century, Sealdah was connected to Goalundo Ghat. Passengers traveling east would disembark at Goalundo from where steamers and boats would ferry them to Narayanganj, where they would again board trains to different destinations of East Bengal. The boatmen on these vessels would reportedly cook up a storm in the form of a meat curry, using basic ingredients. As the boats or steamers flowed across the mighty rivers, the aroma of the curry would float in the air, enticing the passengers, some of whom couldn’t resist asking for a share. From the boatmen, the recipe spread far and wide through the passengers. And the dish carried the name of the place – Goalundo Steamer Curry.