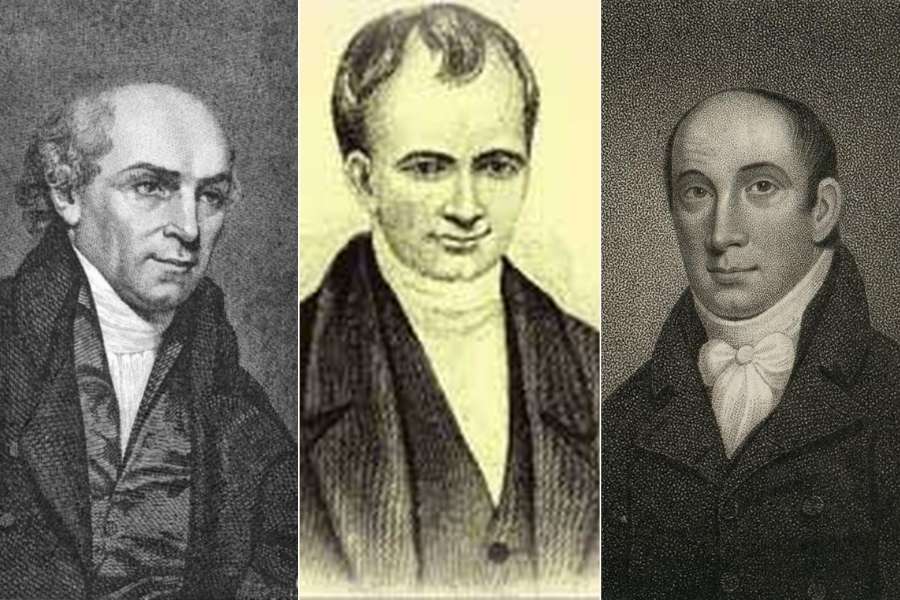

A shoemaker-turned-pastor, a printer and a teacher at a charity school — all connected by the Baptist Church in England — wrote a new chapter in the history of Bengali language, with the support of the Danish government in Serampore in the 18th Century.

Serampore, once known as Frederick Nagore after Danish king Frederick IV, became home to William Carey, a pastor from Northamptonshire county who came to India on behalf of the Baptist Missionary Society. He was joined by two more missionaries — William Ward and Joshua Marshman — a few years later

Carey, born in Pury End, a tiny hamlet of about 100 houses in Paulerspury parish of Northamptonshire County in England, in 1761 went on to play a pivotal role in shaping the history of this far-away land. Carey trained to become a shoemaker, but had a natural love for languages. Despite his humble origins, he taught himself Latin and then Greek, Hebrew, Italian, Dutch and French. He was well-known for doing his reading while working on shoes.

Baptised on October 5, 1783, Carey committed himself to Particular Baptism. The coming years saw him working as a school teacher as well as a pastor before becoming a full-time pastor at a Baptist Church in Leicester in 1789. He was among the founders of the Propagation of the Gospel Amongst the Heathen (later Baptist Missionary Society) in October 1792 and became increasingly engaged in raising funds for directing their attempts at Britain’s colonies.

William Carey began learning the Bengali language, partly out of his own curiosity for languages, but more importantly, to do work for the Baptist Missionary Society

In June 1793, Carey sailed from Britain for Calcutta with his family, finally arriving in the city in November. He began learning the Bengali language, partly out of his own curiosity for languages but more importantly to do work for the Society. Sometime later, he moved to Midnapore to manage indigo plantations there. During the six years Carey spent at the plantation, he translated the New Testament into Bengali and worked extensively on plans to propagate the Baptist ideology.

During this time, more missionaries were sent to Calcutta. Two of them went on to have their names inexorably linked to Carey. William Ward, a printer by trade, who also joined the Baptist faith, had met Carey in 1793 shortly before the latter came to India. Carey had mentioned then that his work in India would need a printer. In May 1799, Ward sailed for Calcutta, accompanied by Joshua Marshman and his wife Hannah. Marshman came from extremely humble origins. He also had joined the Baptist Church and became a teacher at a charity school sponsored by the Church.

Ward and Marshman landed in Calcutta to a hostile reception by the East India Company, which strongly objected to their presence in Company territory. They then decided to move to Serampore to escape harassment. Carey followed.

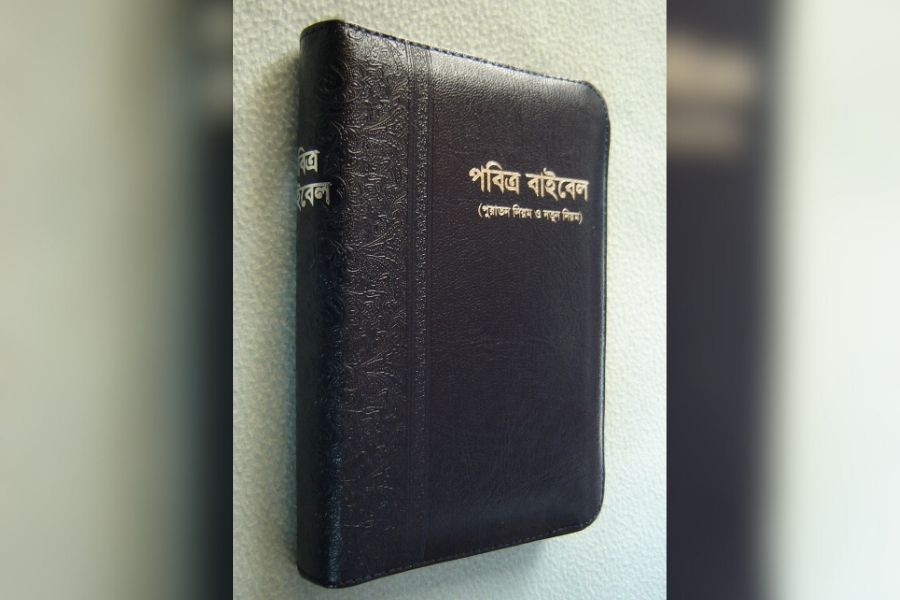

Ward soon went to work, setting up a print shop with a secondhand press arranged by Carey. His first task was to print copies of the Bible in Bengali. The local Danish administration was supportive of their efforts.

William Ward’s first task was to print copies of the Bible in Bengali

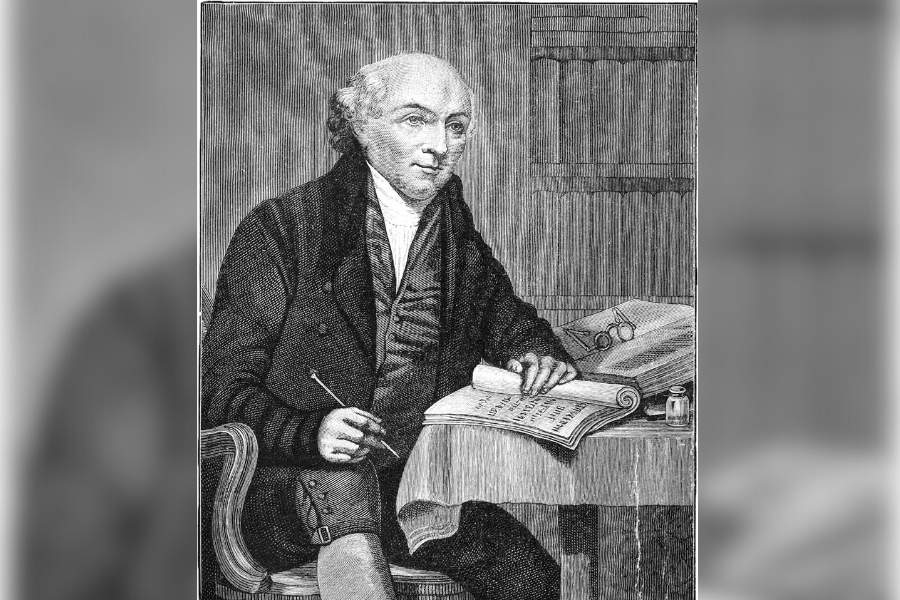

In 1798, Richard Wellesley became the new Governor General and he was more sympathetic towards their cause than his predecessors.

When Lord Wellesley founded the Fort William College in August 1800 for training civil servants, he invited Carey to take up the post of Bengali professor. It was while teaching there that Carey picked up Sanskrit from one of his colleagues. He began translating the Bible into Sanskrit and also campaigned against infanticide and sati daha.

In January of 1800, Ward’s print shop took the more definitive shape of the Serampore Mission Press. Over the next 32 years, it published over two lakh books. These included Christian religious works, translations of the Bible in 25 Indian languages as well as some South-Asian languages, but more importantly vernacular textbooks. While teaching at Fort William College, Carey had started working on Bengali and Sanskrit grammar. The Serampore Mission Press published grammar books in both these languages and a few others besides dictionaries, history, legends as well as moral tales for Fort William College and the Calcutta School Book Society.

In July 1801, under the persuasion of Carey, Ramarama Bosu wrote The History of Raja Pritapaditya, which became the first Bengali prose published by the Mission Press. In late 1804, Hetopudes (Hitapodesh) was published and two years later the Sanskrit Ramayana with a prose translation and explanatory notes by Carey and Marshman. The Press published works in Marathi, Oriya, Assamese and even Kashmiri.

The first Bengali magazine, Digdarshan, was published from Serampore Press in April 1818. Buoyed by its success, Samachar Darpan, the first Bengali newspaper (first Indian newspaper, according to some), was published the very next month.

Joshua Marshman’s role in the growth of Bengali newspapers and magazines has remained largely unacknowledged. He was the prime mover behind the establishment of both ‘Digdarshan’ and ‘Samachar Darpan’

Marshman’s role in the growth of Bengali newspapers and magazines has remained largely unacknowledged. He was the prime mover behind the establishment of both Digdarshan and Samachar Darpan. In both these ventures, he was assisted by his son John Clark, who, in 1821, established the periodical Friend of India, which gained immense popularity. Clark also established a paper mill at the Mission to manufacture a new type of paper resistant to white ants. The paper came to be known as Serampore paper and was soon used across the Bengal province.

The trio’s work didn’t stop with the Press. Their greatest legacy is the Serampore College. In 1818, they decided that the need of the hour was an educational institution that would train Indian followers of their faith in ministerial duties and also propagate education in humanities and sciences. Thus was born the Serampore College, one of India’s oldest colleges, where education would be imparted irrespective of caste, colour and country.

Soon after the college opened, Ward returned to England because of poor health. Back home, he worked tirelessly to secure funds and grants for the Serampore College. He travelled across England and Scotland and even visited Holland and Germany for this. In 1820, he went to New York and travelled extensively across the USA over the next year to raise funds. In May 1821, Ward once again sailed for India, carrying a sizeable tranche of funds for the college. Sadly, he did not live long enough to see the college’s glory day. He died in 1823 from cholera.

Carey, Ward and Marshman’s greatest legacy is the Serampore College

Serampore College was accorded university status by King Frederick VI of Denmark by a Royal Charter on February 23, 1827. It now had the right to award degrees to students. Carrey, Marshman (who had travelled to Denmark the previous year with the appeal) and Clark were the first council members of the university. Serampore College is today one of the oldest continuously running universities of Asia.

Carey left the Mission following disagreements with newer members in his final years and devoted himself entirely to the college. He passed away in 1834, followed three years later by Marshman. By then, Mission Press was on the verge of closure because of mounting losses.

Clark did his best to keep Serampore College running, putting in his own money from the paper mill. Struggling for funds, Clark eventually joined the Bengal Government as the official Bengali translator and handed over his annual salary of GBP 1,000 to the College.

In 1845, Denmark handed over Serampore to the British. Within a decade, the Press ceased operations. That same year, Clark resigned from his government job and returned to England after handing over the college operations to the Baptist Mission Society.

The Serampore Trio (and their associates) may have come to India to propagate their professed religion but their work in the spread of education in Bengali and other vernacular languages despite financial constraints was indeed groundbreaking. But for their efforts, the story of the Bengali race may have followed a very different trajectory.