It's a grim Thursday evening. Minutes away from the bustling Beckbagan crossing, a calming silence prevails at Padatik Theatre. The lights are on and with no play scheduled for the day, Vinay Sharma is immersed in thought when My Kolkata meets the artistic director of Padatik for a chat on theatre.

Finding his footing

One of the most prolific Hindi thespians in Kolkata, Sharma’s stint with theatre began in Bengali. “My father was also an actor (Sarbendra). He did a lot of Bangla theatre and also a few Bangla films (Adwitiya, Shudhu Ekti Bochhor, Nayika Sangbad) in the Sixties. I grew up watching him, so it must have influenced my move to theatre,” he said.

Sharma confessed to being in awe of the commercial Bengali theatre that he predominantly watched. “I fondly remember going to theatres mostly in north Kolkata, particularly Rangmahal Theatre Hall, Kasi Biswanath Mancha and Circarina. Being a south Kolkata boy, it was like an excursion for me. The plays staged there knew how to reach out to the audience. The commercial Bangla theatre circuit grasped the pulse of the audience even before Bollywood and Kollywood. At the end of every major thematic scene, there would be amazing applause, something that rarely happens now. It was a culture where merely seeing icons on stage would bring uproar among audiences.”

The transition from a viewer to a performer was also in a different domain. Sharma started performing English language theatre while studying at Don Bosco High School, Park Circus. “We had a rich tradition where everyone was welcome to audition for the school concert. Our culture was such that even the principal would sometimes join the production. You could simply be a part of the chorus if not anything else and that’s how I started too.” Sharma broke into a smile as he reminisced about speaking his first line onstage in Class IV.

Within four years, Sharma had become a part of the school’s drama scene and was studying plays like Macbeth, Julius Caesar and Merchant of Venice. “Now, people realise the importance of theatre in education, but we had a dedicated drama teacher even back then.”

Having experienced only Bengali and English Language theatre for most of his childhood, few would have expected him to venture into Hindi theatre as an adult. Sharma admitted that his entry into the world was quite accidental. “In 1981, I got done with my ISC exams and was looking for something to do during the three-month vacation. I saw an advertisement in the papers, mentioning that this space, Padatik, was looking for actors. Three of us friends walked in to audition, but were shocked to find that the production was in Hindi. We turned and walked out, but were accosted by a Padatik actor on our way. When we told him that we were leaving without auditioning because it was in Hindi, he confessed that being a Bengali, he wrote his lines in English and then adapted to Hindi.” His encouragement worked and Sharma went back in. This began his long-standing association with Padatik, which continues to this day.

Building bridges across languages

In fact, his lives in English language theatre and Hindi theatre intersected in a unique way. “In Class XI, we were preparing a production of Hamlet for the British Council. Our teacher said that she would call a former student from our school, who had performed as Hamlet in 1973. He was Jayant Kripalani!” As fate would have it, the first Hindi play Sharma saw in Kolkata was an adaptation of Molière by Padatik, with Jayant Kripalani as the lead actor. “He significantly helped us ease up in terms of movement and stance.”

On stage for Mark Twain

Sharma believes that the juxtaposition of three different styles of theatre allowed him to draw specific learnings from each one and use it to his advantage. “The plays we did in school made us form an aspirational world in the English language, while also imbibing its ethos. There was also scope for cultural exchange from the Shakespeare plays that would annually travel from the UK.” He elaborated how the English language theatre from his days at St. Xavier’s College was very uninhibited, and couldn’t have been done in any Indian language. “This brand of theatre opened up minds in terms of textual content, physical expression and the boldness of approach.”

From Bangla theatre, Sharma learnt professionalism. “The actors would perform the same show thrice a week, for weeks on end, where some plays often went on for 500 to 1000 shows, at the same venue. Watching them made me fall in love with the smell and aura of theatre. I found the attraction of being on stage and eliciting that response in unnoticed ways.”

In addition to the semantics, the themes of Bangla theatre also made a mark, since they dealt with social issues of the time. “Some plays openly talked about relationships and many were very bold for the era. There was even a tradition of cabaret dancers walking into the play!”

Bengali theatre of the time was way more audacious than its Hindi counterpart, which he described as ‘a little cloistered’, according to Sharma.

“Kolkata’s Hindi theatre at the time was mostly governed by Sangit Kala Mandir and Anamika, which had a certain conservativeness in the texts they selected and boundaries they set. However, Shyamanandji (founder of Padatik) was known for pushing the envelope and taking on bold themes. Within a year of starting the group, he brought contemporary Marathi plays like Sakharam Binder by Vijay Tendulkar, which was known for its boldness and caused a stir with its portrayal of sexual instinct,” Sharma said. He also attributed it to the revolution happening in Kolkata theatre scene in the 80s, where there was a liberalisation of content and expression for performers and directors. This wave has culminated in the last seven years, when all restrictions have evaporated for creators, he said. “We were lucky to start when we had the best of all three worlds.”

A man of diverse talents

It is perhaps the diversity of influence that has made Sharma’s productions appealing to audiences across cross sections. He recognises the beauty of how localised theatre was during his youth, but his pragmatic side is quick to add that there is no room for it today. “I think theatre is becoming similar across the country. Kolkata theatre was starkly different earlier, but the world is in a peanut now. Everyone is subject to the same forces, be it political or creative, interpersonal or social. Earlier we didn’t have connectivity, so you could think global only in your delusions. Now, if you think local, you wouldn't even be a small fish in a pond.”

Given how many of his plays have travelled across the country and abroad, Sharma never keeps a specific audience in mind while working on a production. “If I’m doing a play, it's knowing that it can travel. You can’t even limit the audience of a particular region anymore. There have been periods in Kolkata itself with free flows of audiences and times when there is dreadful turnout. Audiences everywhere evolve, every seven to eight years as there is a generational change.” This universal lens has allowed Sharma to take his work beyond the stage too.

In the past few years, Sharma has adapted multiple classics like Frankenstein and Dracula into Hindi audiobooks for Audible, played a role in Aniruddha Roy Chowdhury’s upcoming film, Lost, and is even working on a book of poetry at the moment. On the theatre front, he is working on his upcoming production, Version 1.2, an alternate take on a reality where all nations are united under a dictator.

It is school theatre, Sharma felt, that propelled him into direction as “the actors would pretty much do everything themselves”. He formally forayed into direction in 1987, when he joined an alternative education programme called Happy Hours (founded by Madhulika Khaitan & Prof. Sukumar Mitra). “The idea was to interact with children aged between four and 16 after school and expose them to co-curricular ideas which weren’t taught in the classroom. Our motto was inspired by Swami Vivekanda: Children are not vessels to be filled but lamps to be lit.” This also gave Sharma a chance to channelise his inner playwright, as he created original scripts around themes like India, space, evolution, language and colour. These concepts were incorporated into an annual performance with the kids, which imparted knowledge in the simplest manner possible.

Sharma directed his first play for Padatik in 1991 — Ek Anarchist ki Ittefaqia Maut adapted from a text by Dario Fo.

When prodded about the diverse roles he dons on and off the stage, Sharma said he didn’t see himself as a director, but a creator. “Everytime I begin creating something, it happens in a creative vacuum. It’s similar to how actors walk into a rehearsal space leaving their baggage behind. You need to come to a blank space with a blank mind. Your tried and tested techniques work subconsciously when you approach something new, but you never know how the pieces come together.”

Asking the right questions

As a writer, Sharma has a penchant for different themes. “One of the things dominant in my writing is a preoccupation with violence. I can’t comprehend the places to which violence can go, and lead all of us. We are wired to be violent. Besides that love, loss and absence remain prominent themes in my work.” In Ek Anarchist ki Ittefaqia Maut, he chronicled the journey of the Indian state through decades, questioning whether ‘the choice was only between violence and violence’.

He stepped in a new direction in 2005 with Ho Sakta Hai Do Aadmi Do Kursiyaan, the first play he wrote. Sharma questioned recurrent violence in personal relationships, the conflict between authority and personal belief, and whether silence against oppression makes one a subscriber of oppression.

His bluntness isn’t just limited to the topics he chooses, but also in how he sees his craft. “I’ve always tried to create theatre which is personal. I can’t be political sitting on my chair in my drawing room, watching TV and doing f***all about f***all. When I do my theatre, I try very hard not to take sides. I ask questions which torment me. It might seem like asking questions is an escape route to not giving answers, but I think it takes a lot to put your work out there with your name, ask a question to 50 people without knowing their political stances. I like to think that I’m stirring up a hornet’s nest by making two friends sitting next to each other uncomfortable because they believe different things. I hope that when I go onstage to take a bow, some people hate me. I also hope that some people are applauding because the questions affected them, even if for a moment. I hope that they carry these questions back to their drawing room.”

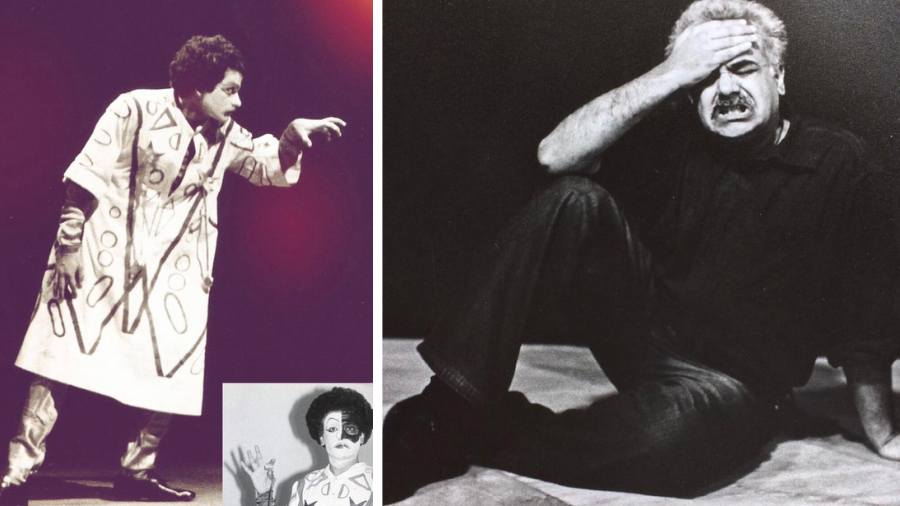

On stage for 'Aur Raja Mar Gaya' and (right) 'Ho Sakta Hai Do Aadmi Do Kursiyan'

A youthful passion lights up Sharma’s face when he talks about where his stories come from. “My education was idealistic and I always found myself to be a misfit in the real world. Compromise became the order of the day and a blind eye was never a blind eye. It felt natural to move towards theatre with a cause driving it, something that went beyond entertainment. I think I’d die if I stopped feeling like a misfit,” he said, adding that this often made critics label his theatre as experimental. “I have no clue if my theatre is experimental, any other ental or any ism. I do believe that it is a theatre of interrogation, not just of self interrogation, but by osmosis, shared interrogation.”

Sharma’s latest play, Dosh, is the story of two middle-aged siblings meeting after a long time and their reminiscence of pleasant memories making way for uncomfortable conversations and hidden secrets. “Through the story of the siblings, the play examines the effects of obedience, guilt and authority on our lives. We wanted to understand why and how an ordinary person obeys unjust orders from an authority figure, even if it compromises their personal freedoms.” The play is expected to come to the city in March 2023, after touring Jaipur, Jabalpur and Mumbai.