I describe my financial existence with the word ‘Trustee.’

This word indicates that I am not the sole maalik of my financial assets; I am only a caretaker or overseer. There is an Urdu word, amaanat, which means that something valuable has been given to me for a short time and I will have to return it to its rightful owner when the time comes.

This amaanat role is like that of a mutual fund strategist, who has been provided a corpus for disciplined allocation without corresponding ownership or inter-generational transmission rights.

This then is my role clarity.

One, I am a steward, not an owner. My role is to manage the amaanat dutifully towards a larger moral purpose (had I been an owner I would have viewed my wealth as a zamindari right that could have been arbitrarily consumed, frittered or invested for personal benefit, no explanations to be provided). What most do not quite get is that ‘nothing belongs to me.’ This goes against the fundamental understanding of ‘I worked for this, so it technically is mine.’

Two, I am driven by a vision that could only play out across the decades as opposed to scattering my money here and now without considering any consequence.

Three, I see myself as accountable to the larger world even as the aggregated zameen-jaaydaad has been earned by my wife and I. In an ownership concept, one could do mannmaani in the way one pleases. There is a line by the poet Shahryaar in the film Umraao Jaan: ‘Tamaam umr ka hisaab maangti hain zindagi.’ I carry a fear that at some point I will be asked: ‘We gave you more than you could use. What did you do with it?’ At that point, the answer ‘8% debt mutual funds’ will not work.

Four, I see social impact as the outcome of my business. Had I been a conventional owner, the only stakeholder to have mattered would have been the capital provider (shareholder) and all disbursable dispensables (donations) could well have been erratic, whim-based and discretionary.

Five, I see myself as having been given a licence to live and work by society; the donation is not an ehsaan but a payment (however incommensurate) of gratitude.

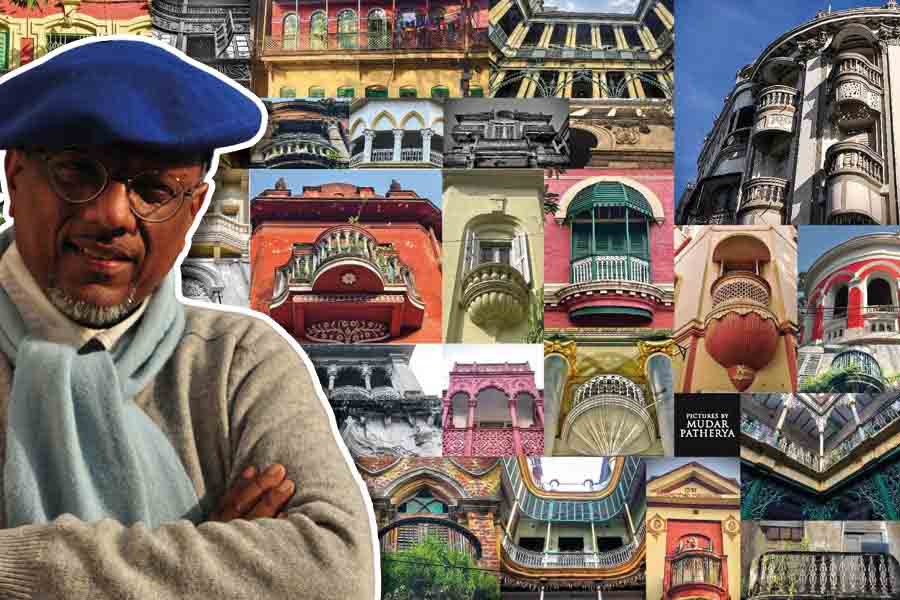

Every single argument to explain our philanthropy ends here: ‘We owe’, writes Mudar Patherya Shutterstock

Six, being a trustee requires creativity as one needs to see possibilities and opportunities in realities, driven not by what is but what can be; the conventional donor’s role is limited to ‘They asked me for a donation of ‘X’ and I gave ‘X’, end of subject.’

This trusteeship revelation did not come as a blinding flash; it was influenced by evolving realities. A large part of our lives have been lived. My wife and I have earned just enough for this zindagi (based on our existing spending pattern that is unlikely to change). Our children have been educated enough to earn a reasonable living. Leaving the children disproportionate financial resources could dilute their life purpose and intensity. And everybody is eventually forgotten (‘Who was the richest man in the Mughal Empire after the emperor?’)

Donation giving is often triggered by mathematics. This comprises a calculation of annual expenses multiplied by the number of years one expects to live plus an additional buffer or provision. If this is considerably less than the available corpus then one is inclined to give away a small part in philanthropy. This is the conventional end-of-line approach, just as a tax paid after all costs have been expensed. The trusteeship concept is different; it places giving away at the head of the profit and loss account. It is embedded in revenues and expenses; it influences the entire personality of the accounting statement. It is not how you will conduct business; it influences how you will live.

It has taken us (my wife and I) decades to arrive at a contrarian understanding of wealth ownership. We earned well because of a maahaul – economic and social – that was not of our making. We were at the right place at the right time; we were unlikely beneficiaries of an economic liberalisation sweeping India through the nineties. We were not smarter than most; we were given an out-of-turn baksheesh by an unseen hand. We were beneficiaries of educational institutions that enriched us more than it enriched the teachers (sadly); we were benefited by social structures that permitted multi-cultural alliances of friendships, partnerships and marriages; we were assisted by individuals who played their small (but influential) roles in our lives and then anonymously exited.

Newton may have stood on the shoulders of giants to get to where he did; we climbed all over these diggaj, we sat on their shoulders while they walked, we heard what they instructed, we received what they funded, we were inspired by them. Standing on their shoulders was the last thing we did.

Over time, the aggregation of these experiences inspired humility more than hubris. Had we been presented an invoice by all these people and agencies for the favours granted, we would have long bankrupted. If an alternative profit and loss account of our lives had been computed, we would have been extensively overdrawn — in contrast to the conventional accounting system. Every single argument to explain our philanthropy ends here: ‘We owe.’

So, when someone asks for the maqsad behind our donation, there is a glib answer for everyone to understand: ‘There is a better return on investment when the money is given to others who are marginalised.’ There is another philosophic glib-ism: ‘Because we are all inter-connected so giving is in a sense receiving. What I am doing for others I am doing for myself.’ There is even a third: ‘How many more pizzas can you eat, how many more cars can you buy, and how many more mansions can you buy before it is enough?’

But there is a reality beyond the glib — that of trusteeship. This gradual enlightenment — that we owe — has been inspired by all the books, people and structures that have played a role in our lives and a ferment of all that has gone inside us.

The concept of the kibbutz comes nazdeek. This unique collective community in Israel, traditionally based on agriculture and communal living, promotes inter-dependance. Everybody lives on the same patch. Someone specialises in one activity, another person in another activity. Finite resources are shared. This reduces economic inequality, enhances education quality, promotes work-life balance, deepens cultural and social activities, and emphasises sustainably simple living. This structure, which promotes giving and receiving at the core of existence as opposed to an end-of-the-line allocation, could have possibly helped transform an Israel of eight million people into the most entrepreneurial per capita start-up community in the world.

Over the decades, similar instances began to get institutionalised in our memory. The Prophet Mohammed’s generosity was described by a biographer as ‘reckless’; he would press silver into the palms of visiting tribal chiefs just when they were leaving; he disbursed liberally from battle spoils with little for himself (‘high payout ratio’). Even though he was ruler of virtually all of Arabia, his personal treasury at the time of his death contained four coins. Of all the descriptions attached to him, the one seldom used for him is what he essentially was — a trustee and pass-through.

The others who demonstrated this trusteeship have been business institutions like Tata Sons where 66 per cent profits go into charitable trusts. The Adanis announced at the wedding of the son of the Group’s founder that they would donate Rs 10,000 cr towards health care and the physically challenged. The industrialist Andrew Carnegie (‘A man who dies rich dies damned’) disbursed nearly 90 per cent of his wealth to build libraries, universities, and cultural institutions. Warren Buffett committed over 99 per cent of his wealth to philanthropy (‘I want to give my kids enough so that they can do anything, but not so much that they can do nothing’) and then co-founded with Bill Gates the Giving Pledge that inspired billionaires to do the same. Chuck Feeney, founder of Duty Free Shoppers, gave away his entire $8 billion fortune secretly, leaving himself with almost nothing when he died.

Trusteeship can be transformative. My wife and I have pledged to give away half our ‘wealth’ (an exaggerated description for what we possess) while we live; we have enunciated causes we are likely to spend on; our children have been driven by ‘How will you contribute?’ more than ‘What will you earn?’. We have a moderate annual expenditure budget addressing personal needs; we seek out passionate social entrepreneurs with a stock picker’s zeal; we back such individuals by issuing ‘donation recommendations’ like a brokerage house’s ‘buy’ pitch; we have extended beyond cheque writing to mentoring and networking social entrepreneurs. The car air-conditioner is used as a last resort to keep the dust out over any refrigeration need; we keep a relatively low personal profile (no pouting lips or restaurant meal pictures in social media posts). Every personal spending is accompanied by an ehsaas (someone’s need could be covered by what we spend). We repair broken or torn possessions— shoes, banyans and pyjamas, mainly — than buy; we drive dented old cars; we still live in the home we bought 30 years ago. Every office meal starts with a serving for our building security; we refer to donation beneficiaries as ‘shareholders’; we would rather meditate with gratitude than go on a pilgrimage; we are engaged in big hoary audacious statements (BHAG) that we seek to transform the destiny of our city (Kolkata, in this case) that are then followed by on-ground initiatives. We would rather ask ‘Can we give out scholarships?’ on a saint’s death anniversary or family event than just feed over-fed people.

Trusteeship needs a de-ego. Trusteeship means under-exposure. Trusteeship means saying ‘I am a momentary speck in time.’ Trusteeship means ‘I don’t matter’ and yet doing everything to matter. Trusteeship also needs a thick skin. When someone says, ‘You are so bloody kanjoos!’, you take it as a nudge that perhaps you may be getting life right.