One of the most powerful novels in World Literature that explores the brutal reality of Colonialism/Postcolonialism and racism, Remembering Babylon by renowned Australian writer David Malouf was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1993 and won the IMPAC Dublin Literary Award.

Thirty years since the novel created waves globally and catapulted Malouf, who will be 90 in a few months, to fame, it has enjoyed a rebirth worldwide and has been resurrected repeatedly with protests like Black Lives Matter and Movements against the killing of Indigenous American girls and students and the targeting of dalits.

Considered an explosive piece of fiction that gestures towards the senseless killing of thousands of indigenous peoples of the world — particularly the US, Canada and Africa — it speaks loudly to the Indian/South Asian history of colonisation.

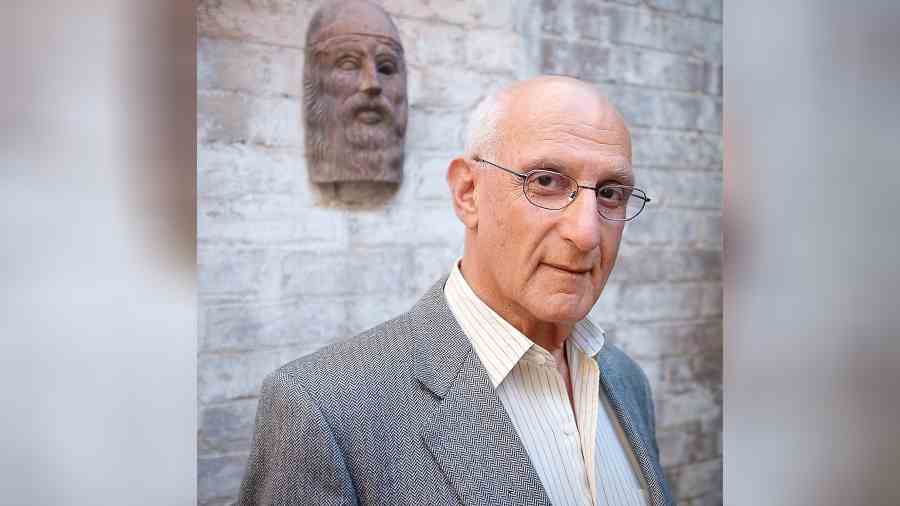

Born in 1934 in Brisbane, Queensland, where he grew up, to a Christian Lebanese father and an English-born mother, David Malouf has lived in Tuscany and England and now resides in Sydney. The fact that he is openly gay textures his lived experience and affords him the multiplicity of vision and voice to understand acutely the issues of colonialism, marginalisation, belonging and not belonging in Australian history, which intersects with our own history of colonialism and casteism in India, to a great extent.

Malouf has a sizeable body of fiction that includes Johnno (1975), An Imaginary Life (1978), Fly Away Peter (1982), Child’s Play (1982), Harland’s Half Acre (1984), The Great World (1990), Remembering Babylon (1993), The Conversations at Curlow Creek (1996), and Ransom (2009).

Applauded in World Literature collections, Remembering Babylon is a story that excavates the egregiousness and inhumanity perpetrated by white Australian settlers from England, specifically Scotland, on the indigenous Aboriginal population of an entire continent. Dazzling in its minimalism and intensely enigmatic, the ultra-racism that is represented in the way the protagonist, Gemmy, a young, ostracised white outcast is othered by his own white settler community, then adopted by the aborigines and finally hunted down by a gang of marauding white settlers, makes the history of colonisation come alive after 75 years of India’s independence to Indian readers.

Remembering Babylon is an embarrassment of literary riches: it has emblazoned in its pages complex issues of identity, power and dominance, marginalisation, the searing pain of isolation, colossal suffering, the colonial desire to dominate through recording and learning everything about the colonial subject’s culture, so their very essence is laid bare and possessed by the coloniser (this is so evocatively represented in the way the Christian minister Mr Fraser uses Gemmy as a native informant for documenting the indigenous flora of Australia).

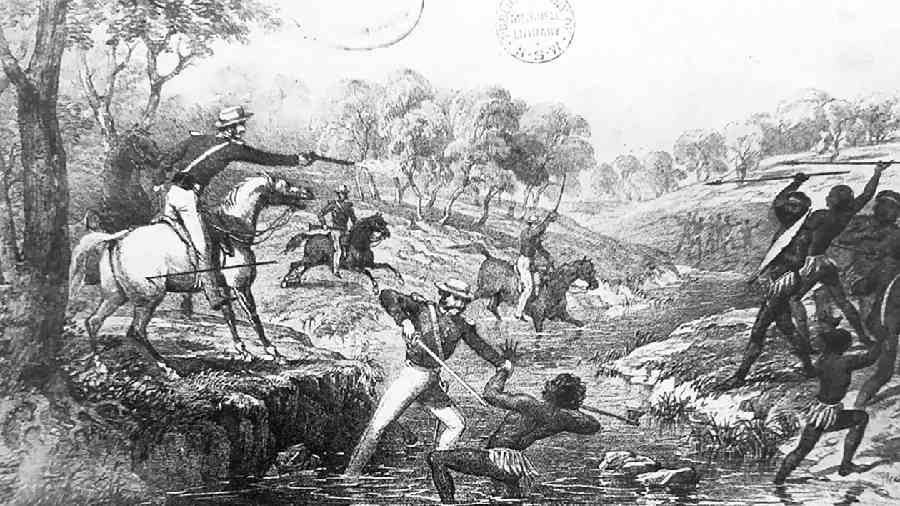

With an extraordinary grasp over language and a deep understanding of human nature, Malouf is also a poet with an enviable collection of poetry. Keenly sensitive to the horror of white domination and racial superiority by settlers in the 1850s who almost wiped out an entire race — the aborigines of Australia — author Malouf delivers a whammy of a story in a minimalist style and is considered one of Australia’s finest writers.

A conflict between white settlers and aborigine tribes in Australia in the first half of the 19th century

The compelling tale, located in the body and mind of Gemmy, who is neither white nor black, but rather white and black at once, unearths the inextricable dualities in human beings adroitly and with deep compassion.At the end of the day, as his old friend Lachlan Beattie finds, decades after Gemmy left the white camp, a small gift of his body that Gemmy had left for Lachlan to discover as Destiny demanded, and share with his sister Janet, who had never married because she had loved Gemmy from that first encounter, when they were ten:“There were bones — not so many. Eight parcels of bark, two of child size, resting a little above eye-level.“He looked at one dried bundle, then another — they were not distinguishable — and felt nothing more for one than for any of them…that this was the place that one of these parcels, which could not be disturbed, contained the bones of a man with a jawbone different from the rest, enlarged joints, the mark of an old break on the left leg, whose wandering at last had come to an end, and this was it.”

REMEMBERING BABYLON: MURDER MOST FOUL

Remembering Babylon

Malouf’s understated narrative has all the eruptive power of a bubbling volcano, and at its narrative best unveils the ugly face of the racial ideology of extermination of the outcast by White settlers.

From the beginning there were those among them, Ned Corcoran was the most vehement, for whom the only way of dealing with blacks was the one that had been given scope elsewhere. ‘We ought to go out,’ he insisted, controlling the spit that flooded his mouth, ‘and get rid of ‘em once and for all. If I catch one of those buggers round my place, I’ll fuckin’ pot him.’

The novel is set in the mid-nineteenth century in the outback of Queensland and deals indirectly with differing and opposing cultures: those of the new white settlers and the Aborigines. This, of course, has already been done by Australian Nobel Laureate Patrick White, still celebrated as a rockstar of fiction, and the guru who was idolised by Malouf.

As White, also a gay writer who understood only too piercingly the pain of being cast out, had done in Fringe, Malouf started out with a historical reference. In a work by F.T. Gregory, Malouf found an account of a certain Gemmy Morril. He later set about inventing the story of Gemmy Fairley, a 28-year-old outcast who suddenly alights on white civilization 600 miles from Brisbane one day in the 1840s.

In remembering the past we learn that Fairley started working for a brutal employer, a rat catcher in London, until he set fire to his master’s house and ran away to sea. After two years at sea, Gemmy is cast overboard off the Australian coast and is taken in by Aborigines for 16 years until his visit to white civilization at the beginning of the book.

Malouf does not deal with Gemmy’s life in aboriginal culture, perhaps because White, his senior, already treated a similar subject — Ellen Roxburgh of Fringe of Leaves — in this light. She is another English sea victim forced to live with Australia’s indigenous population until her return at the end of the novel.

Our introduction to Gemmy is dramatic, replete with irony and unforgettable. After his first words, “Do not shoot. I am a British object,” Gemmy is taken in by a family of Scottish origin, the Mclvors, that has three children: Janet, Meg, and an adopted cousin, Lachlan Beattie. Gemmy is taken in by this family: the “poor savage,” the “halfchild, half sea-calf.” Faced with “monstrous strangeness and unwelcome likeness,” the Mclvors show compassion and sympathy for the outcast.

Their neighbours, however, are full of distrust, hatred, and aggression for what is different: a defenseless, inarticulate intruder. The novel recounts the turbulence and divisions brought to this “savage” white settlement by the confrontation with the Other, in this case a human who falls uneasily into their constricting and primitive categories.

“He lost his old language in the new one that came to his lips. . . As for things, nothing he had dealt with had been his own. He had stammered over most of them. Now they slipped away altogether, they dropped out of his life. And with them and the words went whatever thin threads had held them together, and made up the fabric of his world.

“It was the words he had to get hold of. It was the words that would recognise him. The word flew into his head as fast and clear as the flash and whistle of its breath. Axe. Axe. Circles of meaning rippled away from the mark it blazed in the dark of his skull."

Malouf, celebrated as a master of spatial descriptions, uses a subtle, understated style, in his own characteristic minimalist way to paint a persuasive picture of typical 19th-century Australian outback existence. There is a botanist minister, Mr Frazer, and a 19-yearold, oversensitive, struggling schoolmaster, George Abbot.

The rape of the land and the native flora is another aspect of colonial appropriation of indigenous Australian identity that is a concern signposted by Malouf so subtly when he describes how trees from the British Isles were replanted in Australian soil with utter disregard for local natural beauty, pride or identity: “Good reason that for stripping it, as soon as you could manage, of every vestige of the native, for ringbarking and clearing and reducing it, to what would make it, at last, just a bit like home.”

Says Indrani Roy, who has deep concerns with the issue of identity and has explored the prejudice against differently challenged people and has worked for the Indian Institute of Cerebral Palsy for years: “I found Remembering Babylon amazing, yet horrifying, beautiful though heartbreaking. The poetry of Malouf’s prose is outstanding and his writing captures achingly moving scenes.

“He conveys the brutal power of the geography and the landscape. Delicately, though relentlessly, he focuses on racial intolerance and the question of identity. Gemmy is a truly lonely person. The gulf between him and most of the colonial settlers remains unbridgeable. To them he will always remain a ‘white black fella’, someone to be treated with suspicion and distrust.”

Massacres of the aborigines was done by groups of white settlers in Australia, who took the law into their hands as colonial police. In the history of brutality and colonisation it is well acknowledged that when there is a stereotyping and name calling of the “other” and differentiating “them” from “us”, it is far easier to terrorise the other. Since Gemmy is never one of the whites, though he is biologically white and a British citizen, it was easy to kill him, even if you were white, Christian and raised the same flag.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is an author of Dance of Life and co-author of the bestselling biography Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Kolkata and teaches Masters English at Loreto College