Rana came down to the drawing room, freshly showered and perfumed, at the stroke of seven. The room smelled of flowers. He looked around approvingly.

‘Sabita, get the drinks trolley out, Samik should be arriving soon,’ he called out, placing a record on the turntable.Samik Ghoshal, a rising star in the state’s political firmament, was Rana’s childhood friend. He had been an MLA a few years ago before switching allegiances to become a key member of the party that was tipped to form the government at the Centre in the upcoming elections. In West Bengal, they hadn’t made great inroads yet, but it was Samik’s job to engineer that. Whenever he came by for dinner, at least once a month, all the talk centred on politics, in which Rana had a keen interest. Samik usually came alone, being a confirmed bachelor.

‘All my affections are pledged at the feet of Bharat Mata; she is the one for me, Boudi. Besides, which woman in her right mind would wish to spend her life with a charmless soul like me?’ he would tell Ila, when in the mood for banter.

Sabita wheeled in the trolley, on which were arranged bottles of cold water, soda and tonic, and an icebox. She opened the bar cabinet and picked out liquor bottles – gin for Ila Boudi, whiskies for the gentlemen. Just then, she heard a loud shout from the staircase and turned around. The whisky bottle in her hand struck the side of the trolley and spun out, crashing to the floor. It had been nothing, just Shubho tripping down the stairs; he now stood frozen near the door, staring at the shattered bottle. Rana stood up from the sofa and screamed,

‘You clumsy bitch!’

And on seeing the bottle that lay broken, got even angrier.‘That was an eighteen-year-old malt you destroyed. Do you know how much it costs? More than a month’s salary of yours!’

Ila rushed down, hearing the mayhem, to find Sabita standing speechless, her head bowed.

‘What happened?’

‘What do you think? These country bumpkins you get hold of … they have no idea of the price of things they are handling. Clumsy oafs! Now, don’t stand there gaping at it, clear up the mess!’ he barked at Sabita.

‘Rana! It must have been an accident. Why are you shouting?’

She placed a hand on Sabita’s arm and said, ‘Go, get a mop. It’s alright, you didn’t do it on purpose.’

Sabita left the room.

‘Shubho, you go to the study for a while.’ He walked away.

She glared at her husband.

‘Did you have to say all that? Just because she cannot answer back? Yes, she works for us but that doesn’t mean … and it’s only a bottle; heaven knows how many dozens you have stowed in that cabinet of yours!’

Ila hardly ever raised her voice. Rana was about to snap back, but held his tongue. Ila waited for Sabita to finish mopping the floor before storming out of the room.

Just then, the doorbell chimed. The guest had arrived.

‘My my, have you been drinking all day, brother? This house smells like a distillery!’ Samik said as he walked into the room. Then, noticing his friend’s flustered face, he asked, ‘Something wrong, Rana?’

‘Don’t ask. That stupid … that maid of ours just broke a bottle of Macallan. Can you believe it?’

Samik made a clucking sound. ‘No matter. It’s a small mugful from the ocean that is the Banerjee cellar. Hundreds more where it came from. Don’t fret, now it is all spilt milk. Sorry, hooch.’

He laughed at his own joke.Rana brightened up. He walked up to the trolley and took two cut glasses.‘Whisky?’‘Whatever you are having, brother. We are men of the soil, used to the coarse stuff.’Rana smiled. ‘Of course, of course. You and your great struggles.’Samik had never really needed to work for money. Born with a silver spoon in his mouth, he now lorded it over the palatial Ghoshalbari in Alipore. This allowed him to dedicate all his energies to the pursuit of power.

Rana returned with the drinks. They raised their glasses.

‘To the masterstroke in Muzaffarnagar,’ quipped Rana, with a sly smile.

‘Rana, you really mustn’t say these things, at least not publicly. All this is only the media’s imagination.’

‘Really? Samik, save this for your election rallies; between us friends, we should be able to call a spade a spade. A riot of this magnitude, with less than eight months to go before the elections, and you want me to believe it is coincidence? Anyway, don’t think I am being judgemental. Quite the contrary, actually. Let people rant, you and I know it is the path to victory.’

‘In that, you may be right, Rana. All this does help us, I won’t deny it. But in our state, it isn’t that relevant.’

‘What are you saying? I think it is most relevant here, actually. More than one in four among us is Muslim, even more than in UP where you are stoking the fires! And our history? Are we strangers to communal violence? Go ask your father, he will tell you,’ said Rana, in an impassioned voice. All that talk about how the two communities lived in harmony here did not fool him. He knew that in their hearts, most Bengali Hindus resented Muslims. They were the Other and would always be.

Samik took a sip of his whisky and asked, with a sly grin, ‘Those party goons are still fingering you, is it?’

‘What else are they capable of, these beggars? During my father’s time, it was the communist thugs, and now these new extortionists, neither left nor right, actually nothing. Anyone who runs a business enterprise in this damn state is easy meat. Sometimes I feel like selling out, leaving this city for good.’

Sabita walked in, carrying a plate of fish fries. Its aroma filled the room.

‘Ah, wonderful! Brother, I must compliment you for finding this jewel. I tell everyone: even Bijoli Grill never made a fish fry like our Sabita Debi.’

Sabita didn’t smile, merely folded her hands in a greeting before walking back to the kitchen.

‘Sometimes I feel it is the only reason I stay back,’ said Rana, lifting a fry.

‘The fry or the fish?’ asked Samik, with a wink.

Once Rana had refilled their glasses, he asked, ‘Anyway, how is it looking, for this time?’

‘Good. We are growing. Don’t expect miracles just yet but our vote-share should jump exponentially. May not give us many seats – that will have to wait. You see, their cadres are strong on the ground, we have to build from the bottom up.’

‘Cadres? You mean those thugs? Don’t you worry about them, Samik. These were the same cadres people mistook for diehard communists, but the moment the wind turned, the rats jumped ship. These are mercenaries. Throw them a few morsels, they will become yours. The more important thing is to capture the imagination of the people. That too will happen; Rome wasn’t built in a day.’

Samik clapped, theatrically.

'I doff my hat to you, Rana. It is you who should be addressing the crowds, not me. A born orator, and politician at heart!'

'No, am too fond of the good life, my friend. Besides, these ups and downs - unavoidable in your game - are not for me. I am the archetypal rice-eating Bong. Leave me in a steady stream of contented family life, any day.'

'That reminds me, Rana, where is Boudi? Out of town or what?'

Rana hesitated.

'No. There was a mild altercation about the broken whisky bottle, just before you arrived. She has gone to her den upstairs. Will go and fetch her before dinner. Come on, drink up.'

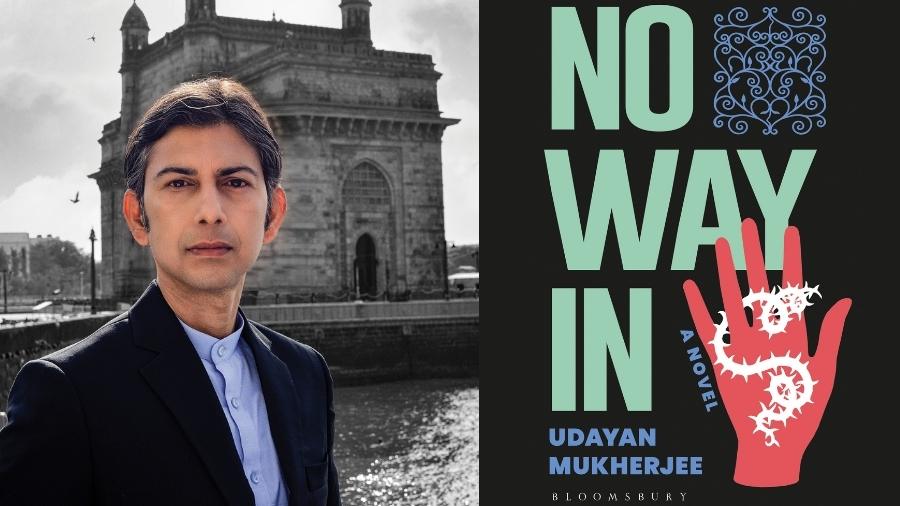

Read more here.