On a weekday morning, Sealdah Station looks rushed like any of our countless railway stations. It is the day after a massive political rally. Many of those who journeyed to Calcutta for it from the suburbs are now waiting to catch a train home. They crowd the north and south platforms. From the looks of it, most of them have spent the night here. Some are eating rice out of tin canisters or lying on sheets of newspaper or nursing sore or injured feet. Regular commuters — office-goers and students — appear irritable as they forge past the sprawl on what they might believe to be their space. The voices of these people, their shuffle, their urgency merge with the announcements, the chugging and hissing of the trains. Should you pause, allow yourself to be immersed in all that noise, to fall deeper and still deeper into residual echoes from years gone by, you just might hear another story.

***

For waves of people, the platforms of Sealdah Station were the only solid ground beneath their feet after Radcliffe sawed the subcontinent east and west in 1947. After the riot in Noakhali in 1946, there had been a steady trickle of people from East Bengal to Calcutta. The trickle became a steady stream in the 1950s. While a lot of people from Barisal and Khulna walked or came along the waterways, some took chartered flights and a vast majority took the train from Benapole or Darshana to Bongaon and onward to Sealdah.

“When the train from Bongaon pulled into Sealdah, there was no room on the platform,” says writer Jatindranath Bala, who arrived in India with his two brothers, their wives and children in the December of 1954. They had fled Jessore, then in East Pakistan, and walked more than 35 kilometres to reach Bongaon station.

Says the 77-year-old, “We went without food and water for three days, and thought we had seen the worst. But that was before we got to Sealdah.”

The Balas lived at Sealdah station for three weeks before moving into a camp near Tribeni in Hooghly district. But for many similarly fated families, the platforms of Sealdah became home for even months.

Artist Jogen Chowdhury, whose own family crossed over from Faridpur, has sketches of Sealdah Station from those times. None of those that The Telegraph interviewed could recall exactly which platforms they had stayed on. Some said Platform 8, many said Platform 5 and 6; written accounts identify a “roped section of the south platforms”.

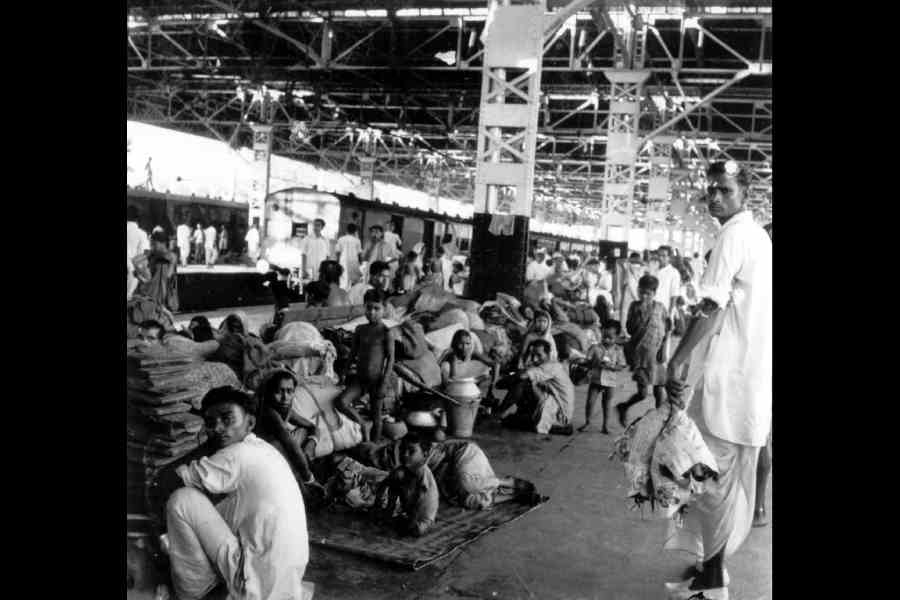

Refugees from East Pakistan at Sealdah Station.

Nemai Ghosh’s 1950 film Chhinnamul shows one such train screech into Sealdah. From it disembark a people who look lost and confused. And in his book The Marginal Men, Prafulla Kumar Chakrabarti describes the first few moments: “As soon as they arrive, they will stand in a queue to be inoculated against cholera and other diseases. Then, along with all family members, they will have to stand in front of the office of the relief and rehabilitation department, where they will be given a certificate stating they are eligible for shelter in relief camps.”

Malati Majumder, 80, was only seven when she arrived at Sealdah. That was 1951. Along with her uncle and his daughter, she had journeyed from Barisal to Khulna to Benapole, Bongaon and finally, Sealdah. She says, “As soon as the train stopped, the cries and screams from the platform intensified. I clutched my uncle’s hand tightly.”

Unlike Bala and many others, Malati had a shelter in the city. She describes the ride in a horse-drawn carriage to that address. It was around the time of Durga Puja and the city wore a festive look. Malati remembers her younger self wondering at the stark contrast.

Adhir Biswas, who is the owner of Gangchil publication, says, “I was only 10 years old when I got off at Sealdah with my parents. Every morning, they would hose down the platforms. Then the police would come and try to remove us.”

Many started living in abandoned railway coaches, says writer and historian Kapil Krishna Thakur. “Some NGOs and Ramkrishna Mission volunteers used to distribute dry food,” he adds.

And that’s how one memory feeds into another; like pieces of a jigsaw, different accounts fill scattered gaps in memory.

Bala says, “The women were afraid to drink water since there were no washrooms around. There were bodies everywhere, women giving birth, others lying injured, many groaning in pain, some inching towards death, some already dead. Once a week, the Calcutta Municipal Corporation would come and remove the bodies.” He invokes a phrase from the Bengali version of Chakrabarti’s book — “naraker dwar”, the gateway to hell. Bala says, “I am not entirely at ease with the description, but that is how Chakrabarti had described Sealdah Station.”

Refugees from East Pakistan at Sealdah Station.

Chakrabarti’s book is full of details — the count of taps for drinking water, overflowing lavatories, young girls bathing in front of hundreds of commuters in the open... Bala talks about the stench of the living and the dead. “It was subhuman,” he adds.

Much has been written about the trains from Pakistan that arrived with their dead. Much abounds in cinematic portrayals as well. “The trains to Sealdah were laden with the living,” says Anwesha Sengupta, an assistant professor at the Institute of Development Studies Kolkata. They brought with them odds and ends of their past lives — money stitched into the hems of petticoats, a wooden stool, a couple of brass utensils, a clay idol, a shivling.

Many of those who arrived survived the new life, did well for themselves, but many never recovered lost ground. Thakur says, “I remember one Gouranga-

babu, who would travel to Howrah to sell gamchhas. Later, he went on to become a revenue officer.”

Bala says, “A distant relation, a young woman of 18, went missing from the platform. She was never found again.” In Chhinnamul, goldsmith Monmohan Sarnakar ends up selling “American combs” on the streets of Calcutta.

Sengupta says, “I have come across references of people living on the platforms of Sealdah till as late as 1967.” She adds, “Many preferred it to the relief camps in Jharkhand, Odisha, Bihar, Dandakaranya and even the Andamans.”

***

In 2025, Sealdah is busier than ever. It has 21 platforms; even as this copy goes to press, some expansion work proceeds. That weekday afternoon, trains puff in from Canning, Baruipur, Lakshmikantapur, Namkhana... Thousands rush out. A shopping complex stands perhaps where the office of relief and rehabilitation was. A postbox between Platform 14 and Platform 15 keeps vigil. Outside the station, where refugees once stood in queues to collect ration, food stalls abound. And the stretch beyond the south platforms from where Malati Majumder climbed onto a horse-drawn carriage 74 years ago is now milling with app cabs and yellow taxis.