Invoking the inimitable dramatist Samuel Beckett, master of the Theatre of the Absurd, the latest superstar among the Nobel Laureates, Laszlo Krasznahorkai, responded to the news of his winning the Nobel 2025 as a “catastrophe”. With a whoop of joy, he said he was happy and proud that he could write and tell the world stories in his language, Hungarian. The Nobel comes after he won the Man Booker Prize for his entire body of work in 2015, rather than for a specific novel.

So, this Nobel might actually be one for the translators, too. By showcasing the importance of capturing a culture and a philosophy that lies embedded in the heartbeat of Central Europe, the newest kid on the literary firmament has shone a light on a gallery of European and Asian writers than just British ones. By casting Kafka, Dostoevsky, Melville, Genji, and Cervantes as cameos or imaginary presences in his five novels and many short stories in over a dozen languages, Laszlo has asserted himself as a formidable gallant in the world literary firmament.

At 71, this screenwriter and author was in the august company of contenders for perhaps the most prestigious literary award this year — with Can Xue, Haruki Murakami, Margaret Atwood, and Salman Rushdie, among others. Laszlo, a Hungarian Jew, was born in 1954 in the small town of Gyula in southeast Hungary, near the Romanian border. His father did not tell Laszlo that he was Jewish until he was 10 years old. Perhaps this chutnified his singular identity, and he was able to perceive the world as a polyphonic arena, where in the age of dysfunctionality and dissonance, he was crying out to be heard. The Romanian border with Hungary is rich in stories of dread and darkness, endemic to the cultural ethos of the geographical gloom of the stories of dread that emerge in the very folklore of the land. Dracula and his forces of dread are real in the fabric of the geography.

Our geographies often determine our histories. A far-flung, lonely spot is the location of Krasznahorkai’s first novel, the somewhat sensational Sátántangó, published in Hungarian in 1985 (Satantango in English in 2012), which was a literary sensation in Hungary and considered the author’s breakthrough work. The novel is dark, and as the title portrays, is suggestive — a poverty-stricken bunch of residents on an abandoned collective farm in the Hungarian countryside just before the fall of communism, become the focus of Laszlo’s narrative.

Silence and anticipation reign until the charismatic Irimiás and his friend Petrina, who were believed to be dead, suddenly appear. To the waiting residents, they seem as messengers either of hope or of the last judgement. The satanic element referred to in the title of the book is present in their slave morality and in the pretences of the trickster Irimiás which, effective as they are deceitful, leaving almost all of them tied up in knots. Everyone in the novel is waiting for a miracle to happen, a hope that is from the very outset punctured by the book’s introductory Kafka motto: “In that case, I’ll miss the thing by waiting for it”. The universal echoes in this novel gesture towards a Nigerian writer, also a Nobel Laureate, Wole Soyinka’s Dance of the Forests, a stage play that teeters between the nihilistic world of hopelessness and the disorder of the real one we inhabit. Perhaps now that Laszlo has won the Nobel, more readers will flock to read Satantango because of the dystopia and hopelessness that rule our contemporary world. The novel was made into a much-acclaimed 1994 film in collaboration with the director Béla Tarr.

“God is not made manifest in language, you dope. He is not manifest in anything; he does not exist. God was a mistake.…There is no sense or meaning in anything,” Laszlo states in Satantango.

However, despite the sense of haplessness and dejection, the Nobel Prize awarding committee saw the sheer beauty with which he paints the broken shards of our world, and it is this beauty that they found to be emblematic of his mastery: “For his compelling and visionary oeuvre that, in the midst of apocalyptic terror, reaffirms the power of art”.

“I would leave everything here: the valleys, the hills and the jaybirds from the gardens, I would leave here all the petcocks and the padres, heaven and earth, spring and fall, I would leave here the exit routes, the evenings in the kitchen… I would leave here the thick twilight falling upon the land, gravity, hope, enchantment and tranquility, I would leave here those beloved and those close to me, everything that touched me, everything that shocked me, fascinated and uplifted me, I would leave here the benevolent, the pleasant and the demonically beautiful, I would leave here the budding sprout, every birth and existence…

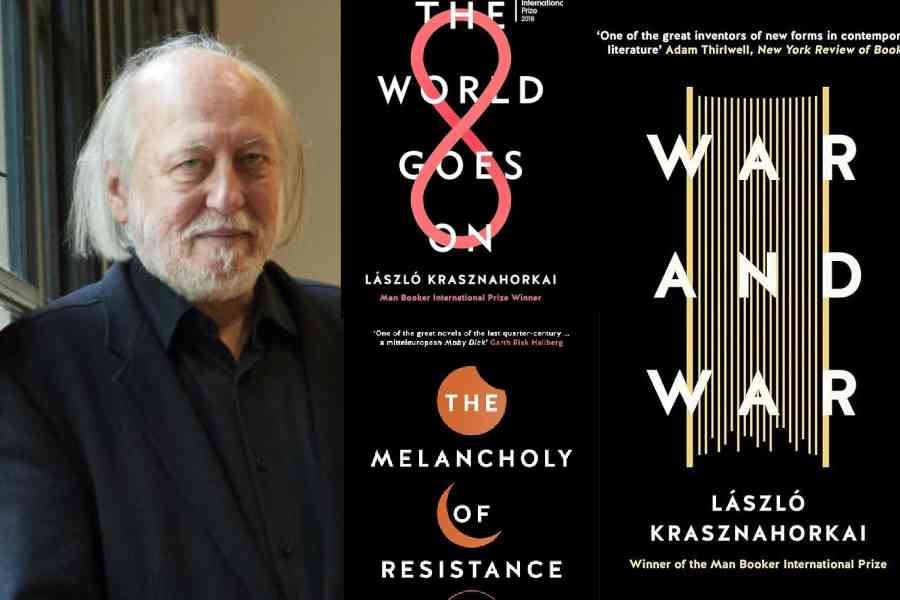

“I would leave this earth and these stars because I would take nothing with me, because I have looked into what’s coming and I don’t need anything from here.” (From his novel The World Goes On)

Most of us who studied Nihilism and Atheism as part of the Western academic syllabus for world literature found Laszlo through American writer and critic Susan Sontag’s laudatory words about Laszlo. Sontag bestowed upon Krasznahorkai contemporary literature’s “master of the apocalypse” tag, a judgement she arrived at after having read the author’s second book, Az ellenállás melankóliája (1989; The Melancholy of Resistance in English in 1998). Here, in a feverish horror fantasy played out in a small Hungarian town nestled in a Carpathian valley, the drama has been heightened even further. From the very first page, we, together with the charmless Mrs Pflaum, find ourselves entering a dizzying state of emergency. Ominous signs abound. Crucial to the dramatic sequence of events is the arrival in the city of a ghostly circus, whose main attraction is the carcass of a giant whale. This mysterious and menacing spectacle sets extreme forces in motion, prompting the spread of both violence and vandalism. Meanwhile, the inability of the military to prevent anarchy creates the possibility of a dictatorial coup. Employing dreamlike scenes and grotesque characterisations, László Krasznahorkai masterfully portrays the brutal struggle between order and disorder. None may escape the effects of terror.

Krasznahorkai is a great epic writer in the Central European tradition that extends through Kafka to Thomas Bernhard, and is characterised by absurdism and grotesque excess. Subsequently, as the Nobel Committee notes, Laszlo looks to the East in adopting a more contemplative, finely calibrated tone.

The result is a string of works inspired by the deep-seated impressions left by his journeys to China and Japan. About the search for a secret garden, his 2003 novel Északról hegy, Délrol tó, Nyugatról utak, Keletrol folyó (A Mountain to the North, a Lake to the South, Paths to the West, a River to the East, in English in 2022) is a mysterious tale with powerful lyrical sections that takes place southeast of Kyoto.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is an author of Dance of Life, the resurrection of culture, post-genocide in Cambodia, and co-author of the bestselling biography Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Calcutta and teaches Masters English at Loreto College, is Literary Columnist for t2 and conceptualises, and curates the Rising Asia Literary Circle