Sadgati, adapted from a short story by Munshi Premchand, was Satyajit Ray’s first and only black-and-white telefilm for Doordarshan. Sadgati means deliverance. The film depicts the persisting caste system and its varying manifestations in post-Independence India. Premchand wrote the story in 1931; Ray adapted it in 1981, much after the Government of India officially outlawed the discriminatory practice of untouchability.

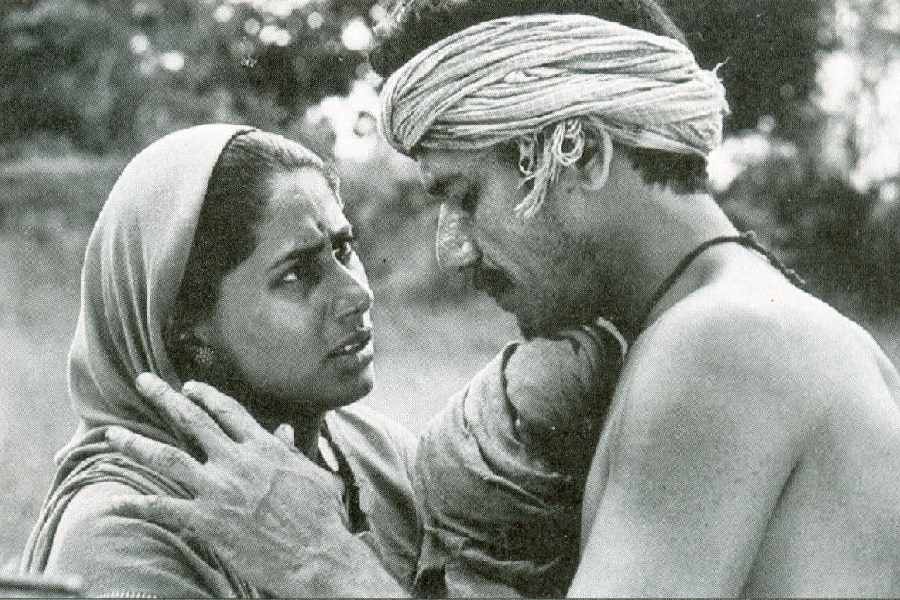

The 50-minute film features Om Puri as the Dalit farmhand Dukhi, Smita Patil as his wife Jhuria, Mohan Agashe as the Brahmin priest and Geeta Kak as the priest’s wife. The black-and-white form enhances the edginess of the tragedy. Puri’s skeletal frame, bent body and almost complete silence when asked to do heavy chores, the action of his blunt axe on the unrelenting block of wood under the blazing sun, all of it makes the telling only too real.

Sadgati is neither the first film on Dalit oppression nor will it be the last. Even if one argues that with films such as Achhut Kanya, Sujata, Ankur, Aakrosh and Sairat, the Dalit found a robust platform within the narrative and cinematographic space of Indian cinema, the Dalit perspective has been largely absent.

The points of view are mainly of a third person, often an upper-caste filmmaker. And while it is true that some significant films have conveyed compellingly the dehumanisation of this class through stories of individual oppressions, it is also true that these individual stories were not representative of the larger Dalit condition. Bimal Roy’s Sujata is an example and so is Govind Nihalani’s Aakrosh.

There have been exceptions wherein classical literature on celluloid has brought the Dalit struggle to the forefront. Among these are — Ray’s Sadgati, Mrinal Sen’s Oka Oorie Katha and Trilok Jetley’s Godaan, all based on Premchand’s works. These films convey the raw reality of being born Dalit.

Ray focused on the irony of the priest who was forced to pull Dukhi’s dead body with a rope tied to his feet. Dukhi was not the priest’s servant. He had only sought a meeting with the priest to fix a time and date for his daughter’s wedding. But the priest made him do very tough work on an empty stomach under the blazing sun and Dukhi, who was already running a high fever, collapsed and died. His wife’s angry lament — she keeps knocking on the closed door of the priest’s house — is all in vain.

Sen’s Oka Oorie Katha suggests just the opposite. It shows how some Dalits can bring about their own ruin and remain immune to the tragedy of the women in the family. Sen was criticised by Premchand scholars for not showing the famous drunken scene wherein the father and son spend the alms collected for the young bride’s kafan or shroud on drinks.

And who can forget Gautam Ghose’s Paar (1984)? It is a screen adaptation of Samaresh Bose’s Bengali story Paari. Instead of simply turning the novel into a film, Ghose used the original story as his base but made the narrative sharper and more hard-hitting.

“To the untouchable, Hinduism is a veritable chamber of horrors,” Ambedkar had once said. Not a single film exploring the Dalit identity has been able to establish that brutal truth.

Prakash Jha’s Aarakshan led to protests by some pro-Dalit groups in Kanpur. They were against the casting of Saif Ali Khan as a Dalit. They objected to the actor’s royal background and regarded this casting as an insult to the community.

These films get rave reviews but do little to change the mindset of the upper castes. In contrast, Nagraj Manjule’s Fandry is convincing because Manjule is himself a Dalit. There is an aspect to Fandry that merits specific comment. It has to do with the portrayal of the family’s vocation which is pig-catching or breeding. Family members are shown unable to go about it effectively. For instance, when their task is to capture a pig, they throw stones at it, which only drives it away. They hate the occupation thrust on them by birth. They despise it so much that they are not bothered about gaining expertise. They know that this source of livelihood is the reason why they are ostracised by society.

The domestic help in Shyam Benegal’s Ankur is shown to be Dalit and also mute. He cannot express his anger even when he understands that his wife is being sexually exploited because she is a servant and the wife of another servant.

Talking about the commercialisation of the Dalit identity, one has to mention Aamir Khan’s box office hit Lagaan. Bhuvan accidentally discovers that Kachra with his limp hand can spin the ball brilliantly. And that is how his disability becomes an asset. Bhuvan includes him in the team. This angers other members who refuse to play with an untouchable but Bhuvan persuades and then at some point Kachra’s talent makes them shed their prejudices.

There are many lesser-known, small-budget films that present a more serious, socio-political image but since the directors were not famous and their films, if released, had a meagre run at the theatres, they remain almost invisible. Some such films are Masaan, Manhole, Chauranga, Kosa, Life of an Outcast, Kastoori, Guthlee Laddu and Swaha.

Films focused on the Dalit identity, unlike Dalit literature, cannot and do not count as a movement towards positive changes in the Dalit condition. It has been nearly half a century since Ray made Sadgati.