|

|

|

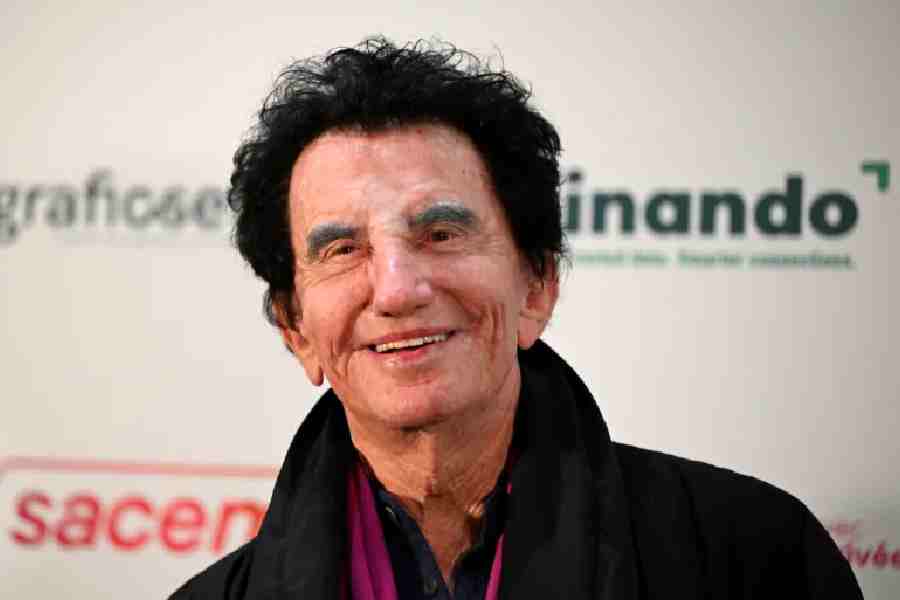

| (From top) Madhubala in Mughal-e-Azam; Aamir Khan in Mangal Pandey and Simi Garewal in Mera Naam Joker |

All’s well that ends well. Or is it? In Bollywood, sometimes that which doesn’t end well is also well. Indian cinema has come a long way from the days of fairytales about rich daddies’ girls and poor mummies’ dudes and ‘happily ever after’. There was a time when a film that did not ooze tears of happiness before “The End” appeared on screen, saw a sad end itself, but not anymore.

“Inquilaab khoon maangta hai,” says Aamir Khan in Ketan Mehta’s Mangal Pandey: The Rising, the film which had eight shows running in a day, even though the leading man dies in the end. Many a film with a not-so-perfect end has bled to death in the past so that today’s tragic tales can hope for more than just a good opening. Raj Kapoor’s Mera Naam Joker, an astounding flop which broke the director financially, was one such sacrificial lamb. The banner’s successive hits were all happy endings.

After Independence, films were the only real entertainment for the middle class. At a time when everyone was struggling to rebuild a life ravaged by the freedom struggle and Partition, they all had enough problems and worries on their shoulders. No one wanted to see messed-up lives on the screen. The idea behind film watching those days was to take a break, sit back, nibble at aloo tikkis brought from home (they were the rage before popcorn swept away all else) and always enjoy the show. It was a classic case of pseudo living where it was essential that the leading man’s problems be solved, even if our own were not! For the “three hours” that they were in the hall, everyone wanted to be suspended in a surreal feel-good world where things really didn’t end till everything got just dandy.

The audience got what they wanted for the most part. But every once in a while, a film defiantly ended without hurriedly tying all threads into one big knot. Chetan Anand’s Haqeeqat, the first Indian ‘war film’, was a major success though the lead pair died in the end. But not too many filmmakers took the chance. The climax of Raj Kapoor’s Aah was changed a little after release to make it more ‘palatable’ to the audience. In the original version of Pyaasa, Guru Dutt had intended for the poet to leave for an unknown life all by himself, but in the released film his girlfriend accompanied him. Except a few stray exceptions like Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zamin, most tragically wrapped up films did little to no business. The viewers were spoilt and pampered and fed what they liked.

But somewhere along the way, the weaning process started. Suddenly, the ‘unhappy’ end was not so untouchable. Most actors preferred a tragic role once in a while to add that dash of variety and extract the ‘sympathy vote’ from the audience. Mehboob Khan’s Mother India was a whopping success which set new standards in the industry. Vijay Anand’s Guide did well at the box-office despite its unusual plot and a depressing end.

Not too many filmmakers had the guts to go the sad-ending way, but those who did, did it gloriously. Films like Namak Haram (Hrishikesh Mukherjee), Anand (Hrishikesh Mukherjee), Shakti (Ramesh Sippy) and Deewaar (Yash Chopra) created milestones in Indian cinema. Filmmakers like Shyam Benegal and Gulzar brought the ‘realistic’ into the mainstream. And realistic films usually called for ends that didn’t always leave us grinning in relief. While no one can question the logic behind the way Ijaazat ended, the box-office didn’t exactly favour the film. On the other hand, Aandhi, which also ended without the quintessential reunion of the leading couple, swept away the box-office.

While films like Saaransh (Mahesh Bhatt), Maachis (Gulzar) and Chandni Bar (Madhur Bhandarkar) have overridden the box-office tide, some seriously good cinema like Ek Doctor Ki Maut (Tapan Sinha), Dil Se (Mani Ratnam) and Parinda (Vidhu Vinod Chopra) has tasted failure only because it ended negatively. Of the recent crop, Khalid Mohamed’s Fiza, Onir’s My Brother...Nikhil and Rituparno Ghosh’s Raincoat were some films with depressing ends that really should have done better.

Interestingly, the Indian audience has been a sucker for tragic love stories. Almost all tragedies of the heart have gone on to become astronomical successes. It started with the mother of all tragedies, K. Asif’s Mughal-e-Azam. This hair-raising tale of the painful love of a prince and a danseuse, which took 10 years to make, has created a history of its own. Many other love epics have been filmed to great success. Heer Ranjha (Chetan Anand), Sohni Mahiwal (Umesh Mehra) and Laila Majnu (H.S. Rawail) were all absolutely beautiful love stories that ended Romeo-Juliet style ? in pain. And all of them were huge successes. Hiren Nag’s Akhiyon Ke Jharokhon Se, K. Balachander’s Ek Duuje Ke Liye, Mansoor Khan’s Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak, Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Devdas and Satish Kaushik’s Tere Naam are some of the love stories which ended in the death of at least one of the lovers, if not both. Perhaps, the tragic end lends a love story a different kind of grandeur. A love story that was amazing in its sad-ending was Nikhil Advani’s Kal Ho Na Ho. Karan Johar probably surprised even himself by letting out of his stable a film in which Shah Rukh did not get the girl.

Hence proved, there is more to a film climax than ‘getting the girl’. And if you still don’t think so, it’s time to wake up and smell the coffee while seeing the films. More and more films leave their ends ‘open’ leaving the audience to decide their own interpretations. Bhandarkar’s Page 3 left us wondering whether Konkona Sensharma would remain on Page 3 and if so would she ever enjoy it again. Mahesh Manjrekar’s Astitva and Mahesh Bhatt’s Arth left us with a hope for the future after an unpleasant past. Just the way we look ahead in real life. Shyam Benegal’s Ankur and Manish Jha’s Matrubhoomi ended symbolically ? showing one thing, but meaning another and raising a question in the process. Aparna Sen’s Mr & Mrs Iyer left us with an uneasy but also a resigned feeling, reinforcing the realism that runs through the entire film. It seemed more like an episode out of someone’s life, less like the climax of a film.

A tangible climax, neatly tied up, is the biggest sign of a formula film. While it can never go out of trend, a formula film is getting to be quite a difficult thing to execute successfully. With the wear and tear of the ‘perfect life’ ending, one almost stands a better chance making a success out of an experimental film. More so these days because the multiplex audience is prepared to let anything become a success as long as it’s done convincingly. They are in the prime of their receptive age. Besides, if every film ended with the same sugar-coated smiles plastered all across the screen, and tears of happiness soaking the curtain through, the halls would be vacated as soon as all the jhatka songs were over. A hatke end stays in the mind long after one has left the theatre. So, if you end a film on a sob note or a shock note, but you do it well, well?all is still well!