It’s a message that Prime Minister Narendra Modi never tires of repeating. India – or should we say Bharat – is the earliest home and the Mother of Democracy.

Modi drove this message home several times during the recent G20 Summit. Delegates were even handed a colourful booklet boldly titled Bharat Mother of Democracy. “Inclusivity". "Freedom". "Harmony", "Equality" and "Acceptability", were the promises on the cover. “We have had a great tradition of democracy for thousands of years,” Modi declares on the first page.

Forget everything you read about King John being forced to sign the Magna Carta in 1215 and laying the foundations of English democracy, liberty and law and establishing that even leaders must obey the law. Democracy was old hat in India by then, according to the booklet.

We can trace democracy, it says, back to what it calls the Sindhu-Saraswati (or Indus Valley Civilisation) culture which existed roughly around 6000 BCE. “In Bharat that is India, the view or the will of the people in governance has been the central part of life since earliest recorded history,” states the booklet. From the village upwards, it was about strong local self-governance every inch of the way.

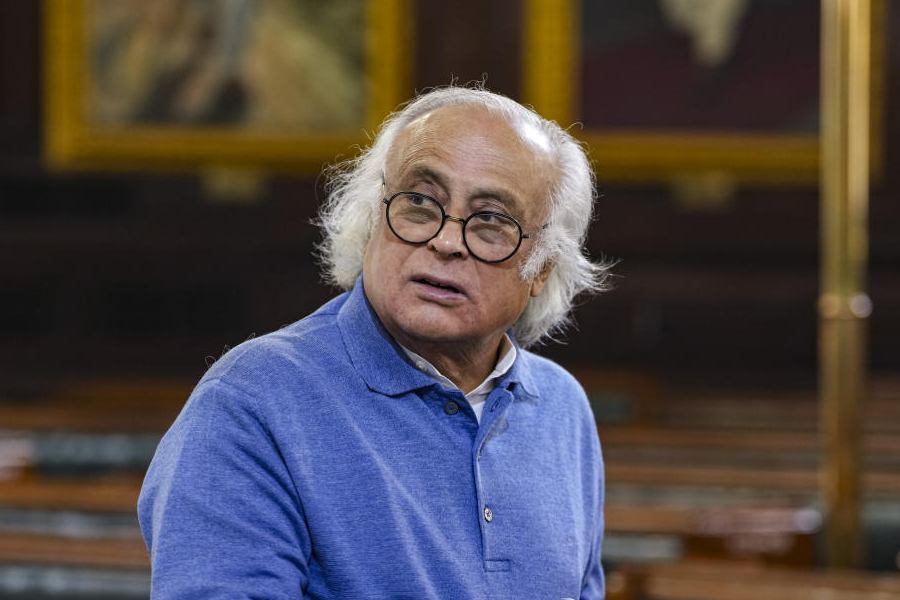

Eminent historian Romila Thapar is sceptical about our new-found claims of being democrats from almost the beginning of recorded history. “Do you think that a society which functions on the basis of caste with its inequality can be called democratic?” she asks.

Yes, insists the government. Indians were natural democrats. The booklet latches onto the point that, “In the Rigveda …… the terms Samiti (assembly of common folk) and Sansad (parliament), each a representative body, find frequent mention.”

Flip through the pages of the Ramayana, it adds, and we find that old King Dasharatha sought the approval of his council of ministers before he could install Rama as the new monarch. Yes, the son did follow the father, but the elders had to give their thumbs up first.

“Democracy is about doing things right for the people,” declares the booklet, saying that this idea emanates from the Mahabharata. But that isn’t quite the usual definition. As one historian points out succinctly: “Democracy is when people have a say in the way they are ruled.” That’s not evident from the booklet.

There’s no doubt that democracy has roots reaching far back in India but so it does throughout the world – in ancient Rome, Carthage, Mexico, Mesopotamia and parts of Africa.

The Licchavi kingdom was one of ancient India’s smaller kingdoms, situated in a part of what is today Assam. The Licchavis are often mentioned as early democracies by people who argue that Indians came to democracy very early. The government booklet, too, mentions them, saying: “In the Licchavi kingdom, 7707 Ganas (delegates) came together to elect their Ganapramukha. They discussed and took decisions in the Santhagara – the central assembly of the republic.”

Buddhism, also, gets a mention and it’s pointed out that the monks got together to decide their leader or vote on key issues. “Decisions were taken by majority. Voting could be through whispering in the ear or by secret ballot.”

The effort to prove that India had democratic traditions that stretched back almost to the beginning of civilised society has a long history. In the early 1900s, historians like K. P. Jayaswal argued that India had democratic traditions right from Vedic times.

There was a background to this view of history. As the Congress began to establish itself and murmurs about self-government began to be heard, the British turned round and offered the argument that Indians had never been able to govern themselves.

Indians countered with the argument that India had age-old democratic traditions. Jayaswal expounded on this in his book Hindu Polity. Other historians, like K. A. Nilakanta Shastry, also insisted that during the Chola era in south India, there were democratic institutions at the village level.

Jawaharlal Nehru, too, made the argument that democratic traditions stretched back to the beginning of civilised society in India. But Nehru argued both ways. At one level, says one historian: “Nehru has made a big point that there were village panchayats that were democratic.”

Nevertheless, adds the historian, “he also pointed out they were not necessarily democratic because any village would be dominated by class and caste." Most crucially, Nehru never claimed India was the Mother of Democracy, no matter how tempting that argument might be in India’s quest for independence.

Through all its pages the booklet appears to confuse the good of the people with their right to democratic choice. It quotes Kautilya’s Arthashastra, written around the 3rd century BCE, saying: “In the happiness of the people lies the happiness of the ruler.” Once again, this is not an indication of the people’s right to choose their rulers.

On page 30 the booklet finally begins to talk about elections. But what elections are these? To guilds and to the town administration. It talks about how Gwalior was ruled by the kottapala or the chief of the fort.

From Gwalior, we zip across the country to Uthiramerur, also spelt Uttaramerur, deep in south India, where the inscriptions talk about elections to elect people to manage the affairs of the village. The booklet doesn’t talk about whether this voting extends to choosing the monarch, who at that time was Parantaka Chola I.

Historian Rajan Gurukkal dismisses the argument that the Uthiramerur inscriptions show there was democracy during the Chola Era. Says Gurukkal: “The Uthiramerur inscriptions of the late 10th century – and the Manur inscriptions of the 8th century – are oft-quoted as evidence of democracy. These are the records of decisions by the village assembly called the Sabha of Brahmin landlords. It was not democracy but oligarchy.” He adds: “There is nothing new to be studied about these inscriptions. It is a well-studied and convincingly described subject.”

Also in south India, Vijaynagar had an assembly of what were called Amarnayakas and a smaller group of ministers. But did the powerful king feel obliged to listen to them? The booklet offers the wisdom that, “Vijayanagar was an example of a state that worked for the benefit of the people.” Was the king elected? The booklet certainly doesn’t mention that.

The Mughals aren’t this government’s favourite dynasty. But Akbar and his Din-i-ilahi do get a mention. “Akbar’s democratic thinking was unusual and way ahead of its time.” Shivaji, too, according to the booklet, consulted a council of ministers. It’s questionable whether powerful rulers like Akbar and Shivaji allowed ministers to question their actions.

What do historians think of the G20 booklet? Historian Kesavan Veluthat heaps scorn upon everything in it. “This is absolute rubbish. From top to bottom. I don’t know how you can compress so much nonsense into so little space.” Veluthat was a professor at Delhi University.

Other historians agree. Says one: “Who are they addressing these claims to? If it’s foreigners, they will all laugh. If it is to Indians, the faithful might say ‘yes, yes.’ The others will be amused.”