|

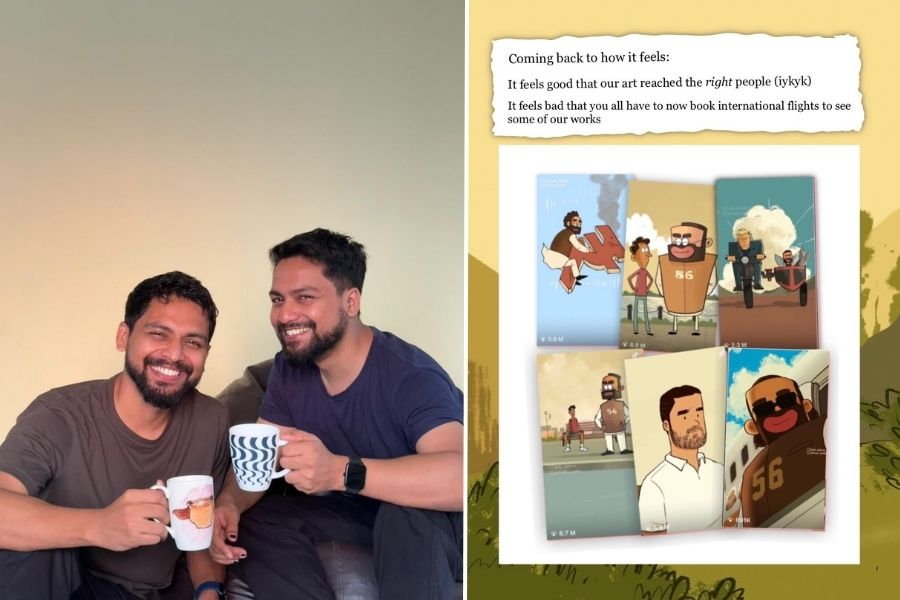

| Business-as-usual traffic in central Cairo on Monday. Picture by Sankarshan Thakur |

If you didn’t know of a place called Tahrir Square in Cairo, or didn’t stir in its direction, you wouldn’t guess there is a revolt blazing that the world is glued to.

This has become a schizophrenic capital, besieged at its heart by a vibrant uprising that refuses to ease its octopus like grip but utterly humdrum beyond the fringe of barbed wire and clay-footed tanks that contain Tahrir Square.

The police and their dreaded undercover cousins, the Mukhabarat, are back on the streets, ordering traffic and seeking papers. Shops and offices are open and banks have long tails of customers hanging out. The downtown is a bumper-to-bumper anarchy of honking and spewing diesel fume. Streetside cafes are rearranging their upended tables and the menus are laid on crisp plaid.

Last night, the party resumed on floating restaurants anchored along the Nile; wine by candle-light on open decks, and lilting music too, although no belly-dancers just yet. And this morning, municipal workers were out with their brooms and barrows, sweeping the bridges on the river, clearing the piled debris as if to say, enough revolution done, let’s get on with it.

“They are saying go, go, but Mubarak is not going, and so?” shrugged one of them on that 6 October bridge, donning his grub-gloves “How long? Either he go, or not go, how long I go without work or money, better Mubarak stay, only six months he said.”

Exactly a fortnight into the eruption of a street revolt to overthrow him, the Egyptian strongman seems to have stopped paying heed to it, as if it were a minor sore that no longer bothered him. He reappeared on national television today, smartly suited and smiling behind a desk in his Heliopolis Palace.

The cabinet sat in court around him, and he benignly nodded as each said his part, not the slightest clue of concern on his visage; he isn’t going to let a few hundred thousand screaming in one precinct of Cairo throw off a 30-year-old regime just like that. “President Hosni Mubarak took a meeting of his cabinet today and took a number of important decisions on economic and other issues before his government,” the Nile TV presenter blandly read.

No mention of the tide that’s risen against him countrywide and coagulated at Tahrir Square. Hosni Mubarak is President of Egypt, it’s business as usual.

Although the fervour of gathered protesters at Tahrir Square continues to flare and flourish, it’s beginning to look like a tragic-comic tableau unfurled in a corner that Cairo is becoming increasingly indifferent to.

Tragic because it has cost hundreds of lives and could become the frustration of a whole nation’s aspiration for democracy and freedom from a relentless and very often brutal dictatorship. Comic because having shaken Mubarak’s throne, they seem lost on just how to throw him out of it.

“It’s a powerful revolt,” said activist Amr Gharbeia, who has been at Tahrir Square since Day One and is beginning to sound a little lost. “But we need a final push and we have to find a way. The aspiration is clear, it needs a push, we have to somehow find that thrust.”

But to Ahmed Badawi, a software engineer who too has invested energy and faith in the uprising, it’s time to begin fearing that the momentum is getting frittered. “Cairo is back to normal almost, Mubarak is still in control and behaving as if nothing happened, we have no leadership that can take this forward, I don’t blame the people for returning to their lives as usual, but are we going to lose this, having come this far?”

The sights and sounds of Tahrir Square still ring of determination. An ad hoc city has sprung up and the hardcore of protesters is bivouacked in tents and lesser shelters, vowing not to leave until Mubarak quits. Tea and food stalls have sprung up, there are dispensaries and first-aid billets littered around for the ill or the wounded.

By sundown, they light fires like in a caravan serai and sing songs of revolution, their arms interlocked, their eyes drooped with sleeplessness. They lie ringed by armoured carriers and tanks that have been trying, slowly but without much success, to squeeze them in, reduce them to no more than a bunch of squatters, a Jantar Mantar vigil if you like.

Everytime the tanks make to move, a group slithers under the treads; the tanks are immobilised. The standoff continues. The Egyptian army, perhaps the key factor in which way the scales tip, remains Sphinx-like, not turning on the protest but not turning its back on Mubarak either. It’s impartial stance still gives the uprising hope and determination but within that lurks fresh doubt. Where are they headed from here? Who is to shepherd them? How?

These past days, Mubarak has decidedly proved himself as wily and resilient as he is despotic; the revolt has looked like it is at its wits’ end, as if it did not think it through.

It sparked off Facebook and Twitter and became a genie that nobody seems to know how to command. Their gains have not been few or mean: they have Mubarak’s word he will retreat in September, son Gamal has escaped to England and lost his job in the ruling party, a few of the corrupt autocrats in the Mubarak establishment have been removed and put under the scanner, and the government has held out the prospect, if not the promise, of constitutional reform.

But all of that still means their key demand has eluded them: Mubarak is still in control, helming Egypt.

His Opposition, on and off Tahrir, is showing sure signs it is not united; indeed by inviting some to talks and ignoring others, Mubarak and his proxies such as Vice-President Omar Suleiman have exposed their schisms and scattered them.

The youths who spearheaded the revolt virtually disowned yesterday’s talks between Suleiman and sections of the Opposition, and vowed to put their own representatives together. The Muslim Brotherhood says it is “reviewing” the government’s offer although it does not trust it.

Supporters of the former IAEA chief Mohammed ElBaradei (who had been left out of the talks) say they were setting up something called the Movement for the Support of Baradei — a new standard banner to add to the many that already attend Tahrir Square and seek its ownership.

“Utter confusion reigns on who actually represents this revolt,” said Imad Hassan, a Cairo businessman. “I am for change but if I subscribe to it and make sacrifices, who is it that I should follow? I don’t know, the protesters themselves don’t know. And so? Where do we go?”

Mubarak might well be reaping the rewards of such uncertainty soaking Egypt’s troubled soul.