New Delhi, Aug. 17: India had identified the sports likeliest to win the country Olympic medals seven years ago but failed to back those dreams with consistent funding in the years leading to the Rio Games.

The sports ministry had in 2009 picked athletics, archery, badminton, boxing, weightlifting, wrestling and shooting as the most probable sources of Olympic medals after the 2008 Beijing Games.

It added tennis and hockey to these seven after the Asian Games of 2014, under a new category of "high priority" sports whose national federations would receive preferential funding from the central government for the Olympics in Rio de Janeiro.

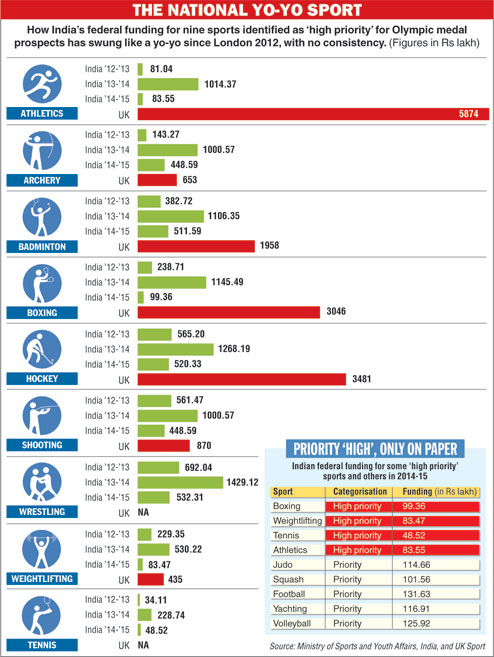

But an analysis of the sports ministry's flow of funds shows bipolar swings year-on-year in the financial assistance the national federations of every one of these nine sports received since the London games, including a sharp dip just two years before the 2016 Olympics. (See chart)

India's strategy of focusing on select sports mirrored the one the UK had adopted before the 2008 Olympics in the run-up to the London Games in 2012.

But Britain followed up its selection of 11 sports with sustained funding, a contrast with what many sports analysts described as India's seesaw-like commitment of resources that has likely contributed to an equally divergent set of outcomes.

The UK is currently in second place in the Rio medals tally with 50 medals, including 19 gold, pushing China to third rank - something it could not manage even at the London Games. India is yet to win its first medal in Rio.

"Unfortunately, we haven't seen the degree of commitment and investments required to identify, train, appropriately expose and prepare potential Olympic-level medal winners," Ashok Ahuja, former head of sports medicine and science at the National Institute of Sports, Patiala, said.

The sports picked by India were selected on the basis of the number of medals they had yielded in the previous Olympics, Asian Games and Commonwealth Games.

But unlike the UK, the pattern in India shows that New Delhi in 2014 funded several sports it considered unlikely to win medals more than the "high priority" picks.

Squash, yachting, football, volleyball, judo and table tennis each received more central funding for their national associations that year than athletics, boxing, tennis and weightlifting. Of these, squash doesn't even figure in the Olympics, and India participated in Rio only in table tennis and judo.

"Unlike the UK, or China, we are investing only in those already at the top level, those who are already proven medal winners," said Rajesh Bhandari, secretary general of the Indian Amateur Boxing Federation. Boxing yielded two medals in the 2012 Olympics. "But when you're preparing for upcoming Olympics, you need to look beyond them."

Overall funding for the "high priority" sports today is higher than it was in earlier decades, said athletes and officials. In some sports, like shooting, that money is also trickling down to junior levels, said Abhinav Bindra, India's only individual Olympic gold medallist who finished fourth in his event this time.

But where India is missing a trick with its investments is in assisting junior sportsmen and sportswomen transition to the far more competitive senior levels, he said.

The Sports Authority of India currently supports about 11,000 promising young sports achievers - in athletics, wrestling, weightlifting, swimming, and gymnastics -between the ages of 10 and 18 years to groom them for future international games.

"That is the missing link in our sports - the support for the transition between junior and senior levels," Bindra told The Telegraph. "Many excellent athletes at the junior levels lose themselves in the transition. That's where we need to put more money than we are right now."

Preparing champions to compete in the Olympics demands an 8-10-year training cycle, said Ahuja, the sports medicine specialist.

"The talent needs to be spotted early," he said. "Promising youngsters need to be supported for eight years through continuous workouts and increasing levels of international exposure - that's what a systematic talent search should aim for."

Some members of sports federations also highlight the need for government support to the families of those being trained for international games.

"Along with talent search and continuous training and support, even the families of promising youngsters should be provided some basic level of care," said Asit Saha, vice-president of the Wrestling Federation of India.

"The mental state of sportspersons determines their performance, and you can't expect the best performance when a sportsperson is worried about what his or her family is eating back home."

But none of these concerns is likely to get addressed unless sportsmen and sportswomen are given charge of the bodies that run sports in India, said Bhandari, a former boxer and a highly regarded coach. At least 10 of national federations of Olympic sports in India are run by politicians - current and former MPs, MLAs and chief ministers.

"Bureaucrats and politicians can never understand the needs of athletes the way one of their own can," Bhandari said. "They can't think of unearthing a talent like (gymnast) Dipa (Karmakar), who has come up completely on her own."