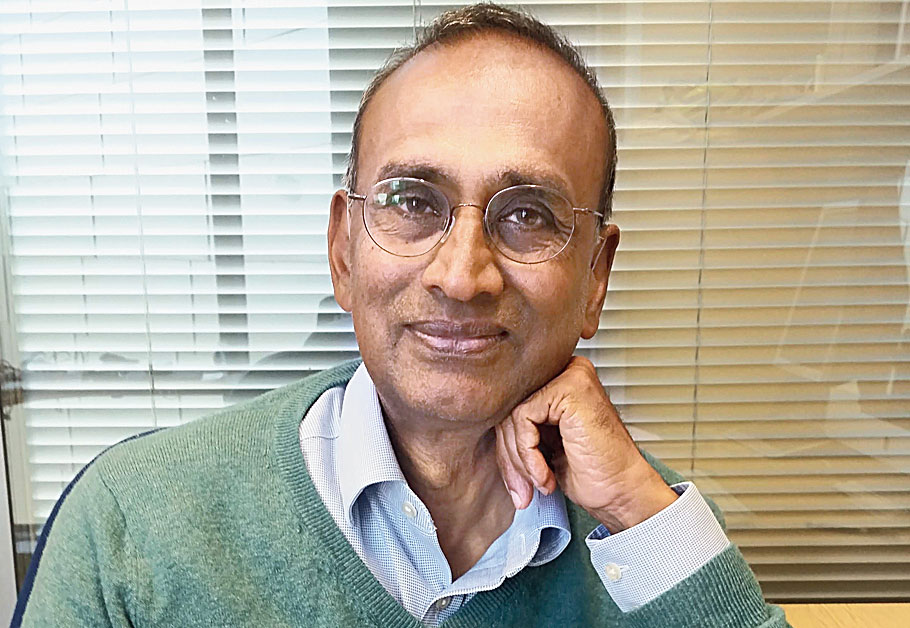

September 20, 2018, marks a big day in the life of even someone who won the Nobel Prize for chemistry in 2009 and then in 2015 became the first Indian to be elected president of the Royal Society.

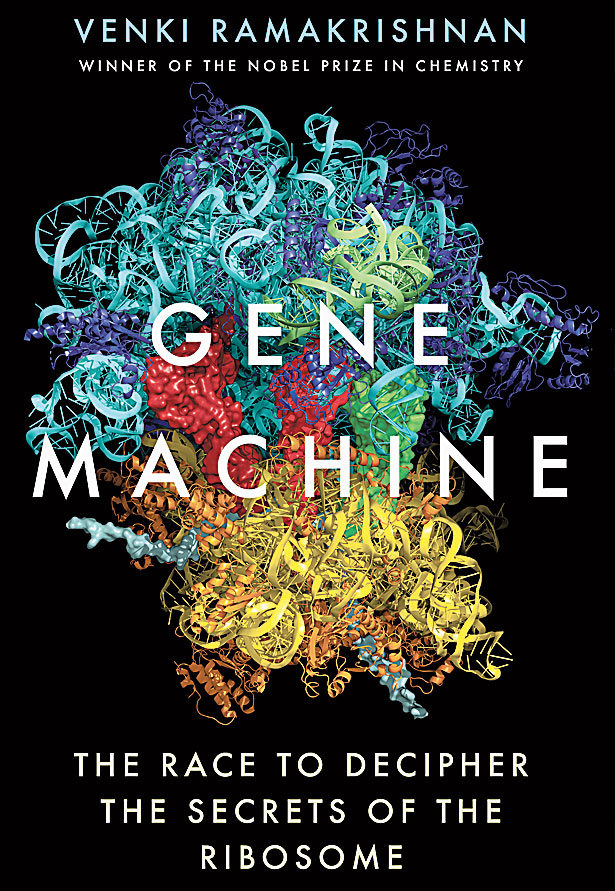

This is because Prof. Sir Venkatraman (“Venki”) Ramakrishnan’s memoirs, Gene Machine: The Race to Decipher the Secrets of the Ribosome (Oneworld; hardback £20), will be published in the UK on Thursday.

Venki, now 66, had settled in Cambridge in 1999 after a career in the US, where he went at 19 after getting his first degree in Baroda.

This might be an odd thing for a Nobel laureate to say but in one chapter, The Politics of Recognition, he writes about the “corruption” that can be caused by the awarding of prizes, which, in his opinion, can distort coverage of the day-to-day work done by scientists.

He writes about the Nobel Prize that “some hanker after it so much it changes their behaviour…. It makes them deeply unhappy and frustrated when, year after year, they fail to get one and is a disease I call pre-Nobelitis”.

“After the prize, there is post-Nobelitis…. They are asked for their opinion on everything under the sun, regardless of their expertise, and it soon goes to their head,” he adds.

It has to be said that the book is very simply written. It is also a fun read. Venki laughs when it is suggested Calcutta might pay him the ultimate compliment by ensuring pirated editions quickly appear on the pavements of College Street. Anyway, he will be in India before too long.

The taxi driver at Cambridge station knows where to go: “Ah, LMB. Francis Crick Avenue.”

At the entrance to the ultra-modern building, which wouldn’t look out of place in Silicon Valley in California, there is a large model of the double helix, representing the discovery of DNA in 1953 by Francis Crick and James Watson. From what Venki says, his baby — the ribosome — is just as important.

Sitting in the small cubicle that serves as his office at the “LMB” (the Medical Research Council’s Laboratory for Molecular Biology), he talks about his book and also what he hopes to achieve in the two years that he has left from his five-year term as president of the Royal Society, the world’s most prestigious gathering of scientists. “The president has an effect in terms of setting priorities and exercising leadership.”

He wants British and European scientists to retain a close working relationship post Brexit; and for the UK to remain open to the world’s brightest talents.

He also wants science to be taught right through school and preferably into university and not dropped at 16, as happens with far too many children in the UK and elsewhere.

The book cover Telegraph picture

Venki, who shared his Nobel Prize with two other scientists for work on ribosomes, says: “The idea of the book is first of all to talk about the ribosome and why it’s important. Here is a small molecule which is older than DNA — almost every molecule in the cell was either made by the ribosome or made by enzymes which were themselves made by the ribosomes. Think of it as the mother or grandmother of all molecules.

“It has links to the origin of life and a central role at the crossroads of biology. It is amazing that if you go to a person in the street and say, ‘DNA’, they all think they know what DNA is, but if you mention ribosome most of them have never heard of it — even most scientists have never heard of it.

“So one goal is to get people to appreciate what an amazing and important molecule it is and how central it is to life. And then a second strain is visualising why was the structure important because when you see what something looks like then you can begin to understand how it works.”

He detects dangers in science being personalised through the awarding of prizes.

This is why “the third strain is about how science depends on lots and lots of people contributing at different stages, sometimes collaborating, sometimes competing; scientific enterprise is not some smooth linear process — it is really very human, full of human failings as well as human tenacity and brilliance.

“The idea is to give a real feeling for how science actually works. And not the whitewashed edited version where you logically go from one step to another and everything is smooth. It is not like that at all.

“People are very competitive, people have egos, and the whole process is often corrupted by prizes and recognition and so on. It is all told from my point of view. I am a bit of an outsider who came from India and went to physics and switched to biology and slowly had to work my way through. I did not go to very prestigious institutions initially and I talk about what it was like to slowly make my way into this problem and then find myself in the middle of this competition; how it all seemed as it unfolded.”

A correction. Sept 22, 2018.

The book was published by Oneworld, not Transworld as reported earlier.