|

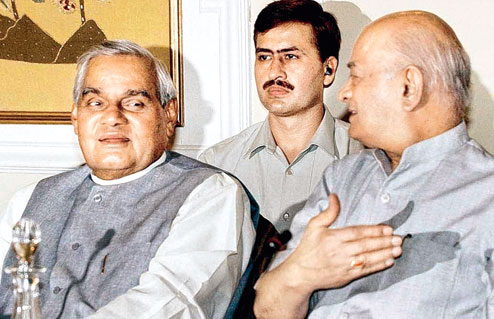

| File picture of Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Brajesh Mishra |

New York, Sept. 30: Brajesh Mishra died the way he lived, articulating Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s opinions and beliefs right until the first Indian national security adviser’s last days.

The untold story of why Mishra abruptly ended his opposition to the Indo-US nuclear deal five years ago was perhaps his final tribute to the country’s unorthodox BJP Prime Minister before Vajpayee drifted into tragic incapacity caused by multiple strokes.

In 2007, Shekhar Tiwari, a lifelong RSS follower from Washington, was visiting New Delhi and Vajpayee invited him to breakfast. Tiwari had hosted both Vajpayee and L.K. Advani in the US, going back to a time when India was so much of a one party-ruled state that the Indian embassy in Washington would not even send anyone to the airport to receive Opposition leaders or maintain any contact with those leaders while they were in America.

Vajpayee invited Mishra also to this breakfast at his home because Tiwari, one of the founders of “Overseas Friends of the BJP”, was instrumental in arranging the NDA government’s courtship with the American Jewish lobby, in which the Prime Minister’s principal secretary was the groom. That was when Vajpayee’s PMO did not trust the Indian mission in Washington to meet the demands of this courtship, which Mishra essentially viewed as a political mission rather than a diplomatic one.

Tiwari has been — and still is — an ardent advocate of intimate engagement between Washington and New Delhi. So when Ranjan Bhattacharya, Vajpayee’s foster son-in-law, walked into this breakfast, he asked Tiwari why he was supporting a nuclear deal which brought no benefits for India. Bhattacharya was, of course, reflecting the BJP’s opposition to the deal. And Mishra’s too, at that time.

But before Tiwari could answer, Vajpayee butted in. “Phayda hai,” Vajpayee said in his style with a firmness that the former Prime Minister uses but rarely, only when he is absolutely convinced of something. “Bahut phayda hoga.” (There are benefits. There will be many benefits.)

Vajpayee had never expressed his support for the nuclear deal in public. His health was already failing, but Mishra got the message. For Vajpayee, the end of India’s nuclear winter has been an obsession since his early days in the Bharatiya Jan Sangh, the BJP’s predecessor.

When Vajpayee was Prime Minister for 13 days he summoned the country’s nuclear scientists on his very second day in office and asked how much time they would need to conduct a nuclear test since the weaponisation process had been complete for several years.

Mishra realised from Vajpayee’s unambiguous reaction to his foster son-in-law’s deprecating tone about the Indo-US nuclear deal implicit in the question to Tiwari that the former Prime Minister viewed the deal as the logical next step to the Pokhran tests the NDA government ordered in 1998.

Shortly thereafter, Mishra ended his opposition to the nuclear deal and stunned the BJP by coming out in support of it. Many interpretations have been given to Mishra’s change of views, but it was his way of preserving Vajpayee’s nuclear legacy in the fading days of his life as a political leader who rose to be the only non-Congress Prime Minister to serve a full five-year term in office.

For Mishra, personal loyalty to Vajpayee, not to his party, was above everything else. On the Prime Minister’s special flight from Durban to New Delhi after the non-aligned summit in South Africa in September 1998, I was discussing with Mishra an issue that cannot yet be divulged because it would break confidences.

I strongly disagreed with Mishra’s action on this particular issue and did not hesitate to tell him so not as a journalist, but taking the liberty of having been his neighbour and walking partner for eight years when he was just another retired ambassador living in east Delhi.

We were standing in front of the Prime Minister’s cabin on the Air India 747 aircraft and chatting. “My sole loyalty is to that man in there,” Mishra pointed to the closed door of Vajpayee’s bedroom. “Can you imagine what will happen if I don’t do this? He will be torn to pieces when we land in Delhi.”

The Prime Minister’s principal secretary was referring to the weakness of the BJP-led government which had come to power six months earlier with a slender majority and the tantrums of an erratic partner, J Jayalalithaa.

When Manmohan Singh arrived at his office on May 22, 2004 after being sworn in as Prime Minister, the very first question he asked was “Where is Brajeshji?” One of the officers in the PMO told Singh that Mishra had cleared his office and left for good the previous day since he was a political appointee and not a government servant.

“But he is a patriot,” the new Prime Minister retorted. “I want to speak to him.” The officer connected Mishra on the phone and Singh requested Mishra to brief him. “I can do that only if Atalji permits,” Mishra replied.

Vajpayee immediately agreed and the next day the principal secretary and national security adviser who had just demitted office went and briefed the incoming Prime Minister. The UPA’s cabinet was still work in progress and the likes of Lalu Prasad were clamouring for key portfolios like home.

Mishra told me later that one piece of advice he gave Singh was that the Prime Minister should bear in mind that India was a nuclear weapons state and the four critical portfolios --- home, defence, external affairs and finance --- should remain with a national party with a pan-Indian and a world view.

It is not known how much weight Singh gave to this bit of advice from Mishra, but the Congress retained the big four jobs and has refused to part with any of these four portfolios despite its allies eyeing them for their leaders, some of whom are among the senior-most politicians in the country.

I once asked Mishra if he had missed anything in his eventful life and if he had any regrets. He recalled his meeting with Mao Zedong on May Day in 1970 on the rostrum of Tiananmen Square. Mishra was charge d’affaires in Beijing, the Indian mission having been without an ambassador as a fallout of the border conflict with China.

It was the first time China’s all-powerful Chairman had spoken to an Indian diplomat since the brief one-month war in 1962. Mao shook Mishra’s hand on the rostrum and told him: “We cannot go on quarrelling like this. We must become friends again. We will become friends again.”

Since Mao’s every word was command for the Chinese people and government, the charge d’affaires understood the historic import of those three sentences. Mishra believed that if East Pakistan had not descended into a separatist crisis within a year forcing China to side with Pakistan, one of only two friends Beijing had --- Albania being the other --- in the whole wide world, a Sino-Indian rapprochement would have followed immediately during Mao’s lifetime.

As it happened, the process had to wait till 1988 when Rajiv Gandhi visited Beijing. Mishra had already retired and his great regret was that the reconciliation did not start during his tenure in Beijing.