|

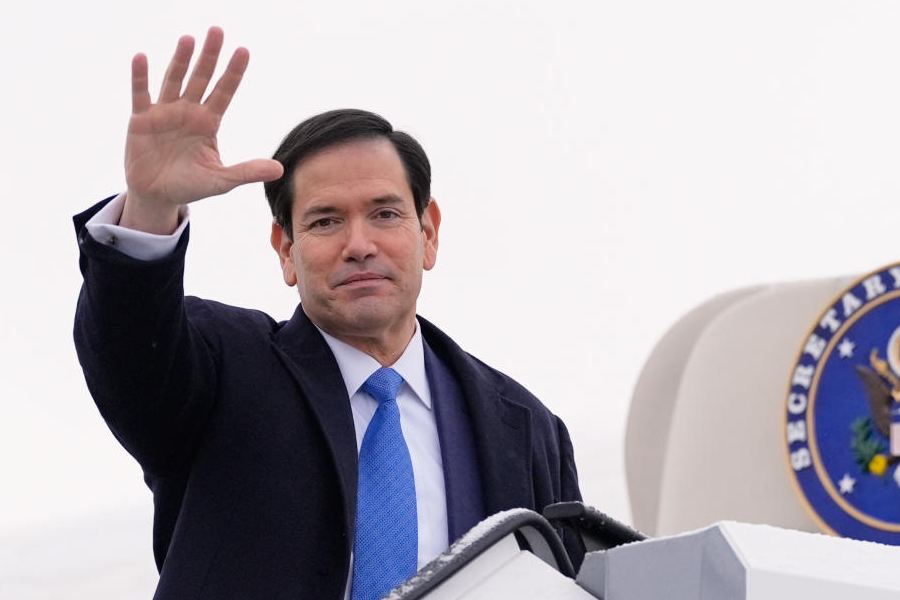

| Nanigopal Maitra, who launched Sulekha |

Calcutta, June 9: If you learnt to write before the age of ballpoint tyranny, it’s unlikely that the name Sulekha would not fetch a whiff of nostalgia heavy with an inky smell.

Sulekha Ink, a symbol of pre-Independence Indian business initiative and ? even rarer ? an example of Bengali entrepreneurship, will be reborn tomorrow after a 17-year shutdown.

“It is a nostalgic moment for me that Sulekha is once again opening,” said 65-year-old Kalyan Kumar Maitra, the managing director, who quit his job as a teacher of chemical engineering at Jadavpur University in 1969 to join the business.

In 1988, technological obsolescence and financial crunch forced Sulekha’s closure. Between then and now, a technological revolution has taken place and the resurrected company ? nostalgia can take a break at this point ? opens a new chapter with a recognition of that change that has affected all of human kind.

Sulekha will make computer printer ink.

It will also produce adhesives, art material, school stationery and home products like phenyl and room fresheners.

All the products will be sold under the Sulekha brand name, which even after long disappearance from the market, commands strong brand equity. Commercial production at a Jadavpur factory will start within three to four months from reopening.

“My son Kaushik and brother Tapananda Brahmachari have worked hard to reopen the factory and we have got cooperation from workers as well,” said Maitra, whose father Nanigopal started the business.

Fired by the zeal of nationalism, Nanigopal and Sankaracharya Maitra set out to sell ink that was prepared by their wives, Purnima and Urmila, and sister-in-law Kalpana at their home in Rajshahi (now in Bangladesh) in 1934.

The two men would hawk the ink, going from door to door. Soon enough, they realised the market was in Calcutta and moved to the city, starting to make ink in a small space at Bowbazar.

By 1946, the two brothers had gathered the wherewithal to buy a farmhouse at Jadavpur from a Gujarati and set up a factory there. As the brand became popular throughout the country, the Maitras ventured into northern India ? to Ghaziabad, which has now turned into a business hub. Another factory came up at Sodepur, in Calcutta’s suburbs.

Sulekha even provided technical assistance to the Kenyan government to set up an ink factory in that country.

But as demand for fountain pen ink waned with the advent of new writing instruments that grabbed public fancy because of their convenience, Sulekha’s books were smudged with red. Unable to bear, the company declared suspension of work in December 1988.

In 1993, the company went into liquidation. The revival attempt began when it submitted a Rs 9-crore rehabilitation scheme to the industrial reconstruction department of the Bengal government. It was approved last April.

“We are indebted to our chief minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee who took a personal interest in reopening the company,” said Kaushik, a mechanical engineer who left the US to breathe life back into the family business.

The company sold 70 per cent of its land (160 cottahs) at its Jadavpur factory for Rs 8 crore and received Rs 1 crore by selling the Ghaziabad property.

It settled debts with the United Bank of India with a payment of Rs 3.32 crore. It also paid back Rs 3.7 lakh to the West Bengal Financial Corporation and another Rs 13 lakh to the Uttar Pradesh Finance Corporation.

“We will clear all the dues of our 550 employees and the payment will begin from tomorrow,” Kaushik said.

Madanmohan Saha, an old employee, could not hide his happiness. “It is true that the workers suffered a lot of agony for 17 years. But we are happy it is reopening and new jobs will be created for the next generation.”

Saha, from the ink generation, would be gladder to know that the fountain pen is back in fashion. Sulekha, he may be assured, will also make writing ink.