India ranks 94 out of 107 nations on the Global Hunger Index 2020, with a “serious” level of hunger that puts it behind every one of its neighbours.

The hunger level is calculated on four indicators: undernourishment, child wasting (children under five who have low weight for their height), child stunting (children under five who have low height for their age), and mortality rate for children under five.

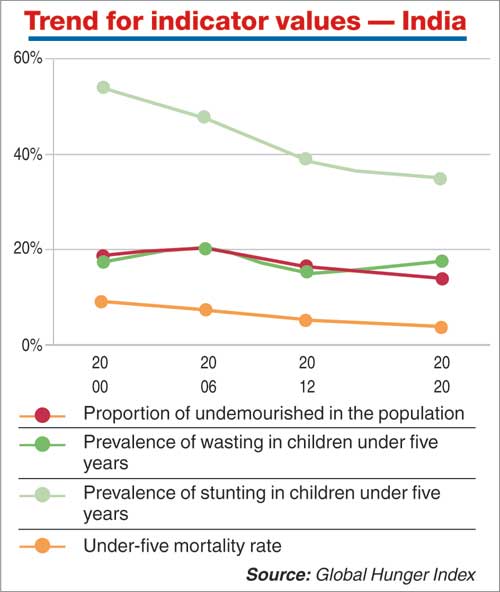

According to the report published by Ireland’s humanitarian agency Concern Worldwide and Germany’s aid agency Welthungerhilfe, prevalence of wasting among children in India, which reflects acute undernutrition, has gone up in the period 2015-2019.

Sudan scored the same as India on the hunger index: 27.2.

Countries which have fared worse than India include North Korea, Rwanda, Nigeria, Afghanistan, Lesotho and Sierra Leone.

A GHI score of less than 9.9 is considered to be low hunger, between 10 and 19.9 is moderate, between 20 and 34.9 is serious, between 35 and 49.9 is alarming, and a score over 50 is extremely alarming hunger.

India’s score was 38.9 in 2000, 37.5 in 2006 and 29.3 in 2012.

Last year, out of 117 countries that were ranked, India stood at 102. Only countries on whom sufficient data are available to calculate the score are ranked. In 2018, India stood at 103 among 119 countries.

Every other country in the subcontinent has fared better in feeding their people than India. Nepal with a score of 19.5 faces moderate hunger and is ranked at 73 and Sri Lanka with a score of 16.3 is even higher at 64. Bangladesh, Myanmar and Pakistan face serious hunger but were placed well above India, at 75, 78 and 88, respectively.

Himanshu, an associate professor of economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University with specialisation on poverty and inequality, said the benefits of economic growth in India were not reaching the public.

“Growth does not mean everybody is benefiting in India. There is huge inequality because the fruits of growth are enjoyed by selected sections of society,” he said.

Himanshu said the benefits can reach more people if the government spends more to improve public education, health care, nutrition, social security and gender empowerment. There is no sign of increase in investment in these areas, he added.

“The neighbouring countries are actually investing more in education, health care and so on for the last over two decades. This report has rightly pointed out the problem. But things are unlikely to change in India going by what we have been seeing,” Himanshu said.

The report presented a case study on Nepal, pointing out that the landlocked country had alarming hunger levels as recently as 2000. Interventions to improve children’s health have done a great deal to reduce child mortality and raise children’s nutritional status.

India in August 2019 had passed a law to ensure workers do not get wages less than a minimum threshold level notified by the Centre, but the rules are still to be finalised.

The economic contraction associated with the pandemic could increase the number of children who experience wasting in low and middle-income countries by 6.7 million, the report said. The report has significance for India since its GDP for the first quarter of this financial year was minus 23 per cent.

The mortality rate of children under age five in South Asia as of 2018 was 4.1 per cent. India experienced a decline in under-five mortality in this period, driven largely by decreases in deaths from birth asphyxia or trauma, neonatal infections, pneumonia and diarrhoea. However, child mortality caused by prematurity and low birthweight increased, particularly in poorer states and rural areas, the report said.

According to the report released on Friday, 14 per cent of India’s population is undernourished, the rate of stunting among children under 5 is 37.4 per cent while the rate of wasting among children under 5 is 17.3 per cent. The under-five mortality rate is 3.7 per cent.