Assembly polls in Bihar can be as much a lesson in arithmetic as in sociology.

At first sight, the numbers appear to pose a puzzle.

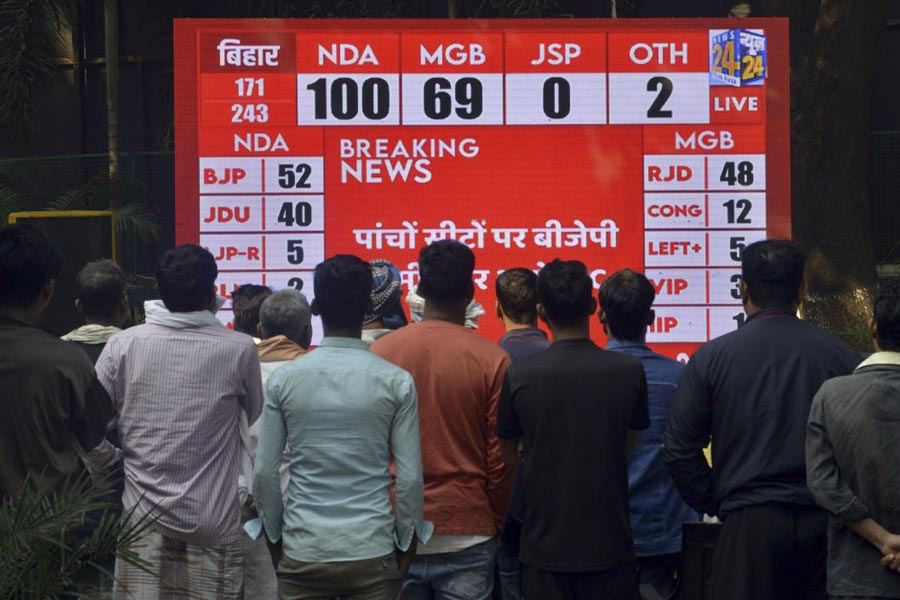

Sample this: At 23 per cent, the RJD’s vote share was marginally higher than the 20.08 per cent polled by the BJP — the single largest party with 89 seats in the Assembly-elect. Yet the RJD won only 25 seats.

The Congress won 27 seats in 2015 with a vote share of merely 6.66 per cent. This time, with a vote share of 8.71 per cent, the party won only

6 seats.

The All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM) won 5 seats with just 1.85 per cent of the votes.

Partly, this is the magic of the first-past-the-post system that many Opposition supporters — driven by the allegations of “vote chori” and suspicion of the special

intensive revision of the electoral rolls — are trying to wrap their heads around.

However, there’s another — simple and logical — answer to the puzzle.

A party’s vote share is calculated as a percentage of the total votes cast in the state. One reason why the RJD’s share is higher than the BJP’s is that its votes came from 143 constituencies as opposed to the BJP’s 101.

And although the AIMIM polled fewer votes than the Congress, these were concentrated in the 25 seats that the Hyderabad-based party contested in contrast to 61 by the Congress.

The Hindu calculated the average number of significant political parties in the fray using a formula known as the Laakso-Taagepara Index. This put the effective number of parties at 2.65 — lower than that in any Bihar Assembly polls since 2005 — indicating this was the most bipolar election.

In this largely one-on-one fight, the NDA consolidated its base through clever caste arithmetic. The Mahagathbandhan’s claims of unity did not convince the voters, who chose parties like the AIMIM in several seats.

Despite inducting new caste-based parties like the Vikassheel Insaan Party (VIP) — which claims to represent the Mallahs — and the India Inclusive Party that is trying to lead the Tanti-Pan community, the Mahagathbandhan’s vote share stagnated at the 2020 levels of 37 to 38 per cent.

The NDA’s, however, rose from 37.26 per cent in 2020 to more than 46 per cent this time. The ruling alliance’s new additions were the Chirag Paswan faction of the Lok Janshakti Party — which claims to represent Dalits, especially Paswans — and the Rashtriya Lok Morcha led by Upendra Kushwaha, from the backward Koeri community.

Chirag’s party brought an almost 5 per cent vote share to the NDA from its own seats, and helped attract votes to its allies in other seats as well.

Why the NDA’s caste arithmetic worked better than the Mahagathbandhan’s is anyone’s guess. The shares of the Mallah and the Tanti-Pan communities in Bihar’s population are estimated in single-digit percentage points. Yet the alliance named VIP leader Mukesh Sahani as a prospective deputy chief minister.

The Muslims — whose leaders have projected them as an electoral bloc and are almost 18 per cent of the population — weren’t offered any such carrot. Both main alliances fielded fewer Muslims than before.

The community responded by voting for the AIMIM in places where they are in the majority. In other places, the AIMIM caused the Mahagathbandhan’s defeat in at least six seats — assuming that most of its supporters wouldn’t have voted for the NDA in the absence of the AIMIM.

The AIMIM is now the party with the most Muslim MLAs in Bihar — a feat it has achieved for the first time outside Telangana. Bihar today has just 10 Muslim MLAs, a record low.

News outlets have pegged Jan Suraaj’s vote share at 3 to 4 per cent. The party appears to have damaged the prospects of both big alliances equally, with its votes higher than the victory margin in 33 seats.

Similarly, the BSP’s votes were higher than the margin in 20 seats, 18 of which were won by the NDA and two by the Mahagathbandhan.

The real impact of the NDA’s success in caste calculations, compared with the Mahagathbandhan’s, can be seen in the contests between the alliances’ flagship members — the JDU and the RJD — in seats where they were the top two parties.

In 2020, the RJD won 40 of 61 such contests. This time, the JDU won 50 of 59.

Was it merely caste that undid the Mahagathbandhan? Random samples of voters interviewed by this newspaper indicate that economic issues were the first thing on their minds.

Hindu women were firmly behind chief minister Nitish Kumar thanks to the ₹10,000 grant for employment. In a state where the effective daily minimum wage barely touches ₹400 in rural areas, and work is hard to come by, ₹10,000 looked like hitting the jackpot, a Durga Puja gift that softened the anti-incumbency.

Without a credible road map from the Mahagathbandhan to generate employment, gratitude for Nitish trumped the discontent against his government.

The male turnout was 62.98 per cent and the female turnout, 71.78 per cent.

The overwhelming economic appeal of the NDA seems to have eclipsed the repeated underperformance by the Congress.

The Congress’s strike rate — the ratio of seats won to those contested — dropped from 27.1 per cent in 2020 to 9.8 per cent this time. The RJD’s fell from 52.1 per cent to 17.5. The Congress can argue in self-defence that it generally contested from seats harder to win.

With the “vote chori” campaign falling flat in its face, the only significant victory the Congress won along its Voter Adhikar Yatra route came in Araria.