|

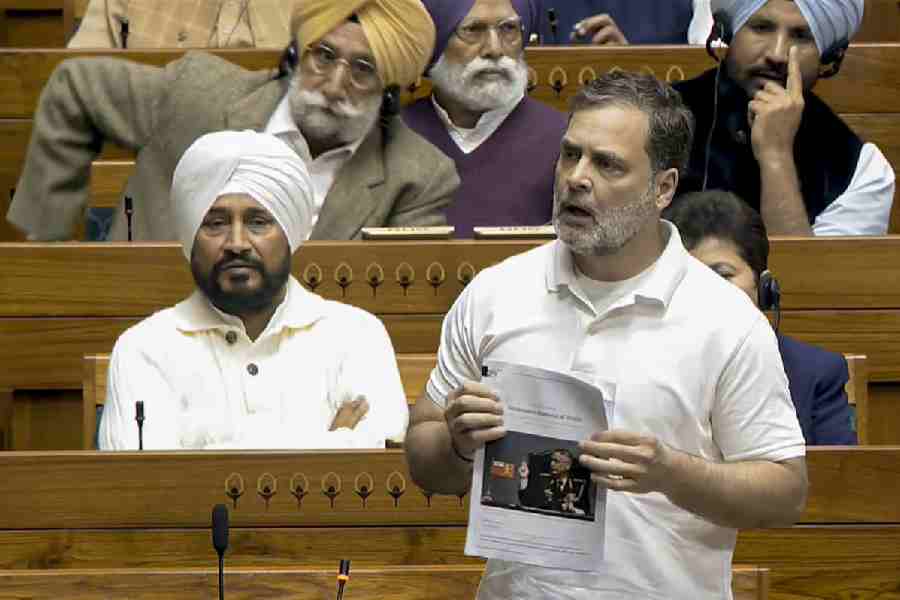

| Shree Bose (right) with Peter Higgs at CERN on the day the presence of Higgs boson was indicated |

Washington, July 23: When scientists announced the landmark discovery of a new subatomic particle at the European Organisation for Nuclear Research, better known as CERN, three weeks ago, seated in the audience were two conspicuously “unscientist-like” men and two similar women all of whom shared the last name “Bose”.

Their presence whetted curiosity at CERN, more so when the renowned British physicist Peter Higgs who originally proposed “the God particle” — as the scientific community calls the discovery — posed for photographs with one Bose, a teenager with the first name Shree.

Shree Bose, until recently a student of Fort Worth Country Day School in Texas, bound for Harvard in September, was in CERN on the Franco-Swiss border purely by chance that day. The 17-year-old girl was there with her parents — mother Prarthana who hails from Icchapur and father Animesh, an IIT Kharagpur alumnus — and brother.

The audience at the announcement of the likely discovery of a particle that Higgs had proposed 48 years ago thought that Shree and other members of the Bose family were there because they were somehow related to eminent physicist, Satyendra Nath Bose.

It was Satyendra Nath Bose who developed the mathematics to describe the behaviour of a set of particles to which the Higgs particle belongs. Hence the collective name of “bosons” for these particles.

CERN’s public affairs officers had proposed the week from June 27 to July 4 for Shree’s visit because that was a time when Proton-B is switched off and she would, therefore, have access to the tunnel where protons collide with each other, which is normally out of bounds for visitors to the organisation. Her visit was part of a grand prize package as the winner of last year’s Google Science Fair, an international competition for students in the ages 13 to 17 with a flair for science.

“By choosing this schedule, I could go to the tunnel and (later) watch the protons when full activity was resumed,” Shree told The Telegraph on the outskirts of Washington where this teenager with promise is doing a summer internship at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) before heading out for Harvard.

She had no idea then that the announcement about the last missing piece in mankind’s search for all the properties of fundamental particles of nature would be made in her presence. “It was a chance in a million or a billion or even larger”, the kind of occurrence that would have made Shree believe in fate, if conversations she listened to in the Bose household had not been about atoms since she was six years old.

“My older brother was the science kid,” Shree told Ashley WennersHerron, a spokesperson for CERN during her visit to the institution. “I was six when he tried to explain atoms to me. He said that if you keep breaking things down, eventually you would get atoms. I loved that. It explained the world, but also maintained its beauty.”

Pinaki Bose, the brother two years her senior, was with Shree when The Telegraph met her last week. He is also doing an internship at the NIH but hopes to stay on there for a while after his sister leaves for Harvard.

It is not often that the NIH, America’s premier medical research agency, engages siblings as interns concurrently, so the Boses are a curiosity there, too.

One NIH employee said he was delighted at the attention that Indian American families pay to the education of their children, reflected in the achievements of the Bose siblings at their very young age.

Pinaki said that at the end of school he used to tell Shree everything he had learned that day so she took an early interest in matters academic.

Because of Pinaki, his sister may well have turned to science, otherwise she may have been inclined to go for the arts, Shree now says.

Two other events impacted Shree at an impressionable age and made her turn to cancer research, the project which got her the grand prize at the Google Science Fair. Both her paternal and maternal grandfather died from cancer.

Like many children who are steeled by tragedy, Shree, who was born in Santa Rosa, California, and later moved with her parents to Fort Worth, Texas, when she was five, determined that she should do something to change the way her grandfathers were snatched away by the disease.

That opportunity came when Alakananda Basu, a Bengali American professor in the department of molecular biology and immunology at the University of North Texas Health Science Center near Shree’s home, allowed the high school student to work in her laboratory in the summer of 2009.

At that time, Basu, who hails from Asansol, was researching the critical issue of molecular drug resistance to ovarian cancer, a project that is now sadly on hold because of funding cuts for academic work due to the economic crunch in the US. Shree worked in Basu’s laboratory again the following summer.

“I did not know Shree or her family, although I suspect I may have met them at the local Durga Puja. But Shree wrote to me out of the blue that she wanted to do cancer research and she was very persistent,” Basu said from her Fort Worth home.

Her project for the Google Science Fair is an offshoot of that work. “I see promise in most of the kids that I engage, but in Shree I found a high school student who was highly motivated even on a very difficult subject for her age.”

So Basu had no hesitation in writing a letter of recommendation for her ongoing internship at the NIH.

At her laboratory, Basu passed on Shree to one of her PhD students, Savitha Sridharan, who is also convinced that reversing and overcoming patient resistance to Cisplatin and its analogues in treating ovarian cancer is vital for mankind as therapy failure causes rising deaths.

Sridharan believes the Google prize is only the beginning for Shree. “She knows that if she works hard she will get what she wants. I often see motivation in my undergraduate students, but that quality in Shree is rare in high school.”

As the grand prize winner in the Google competition, Shree got a $50,000 scholarship fund and a 10-day trip to the Galapagos Islands in addition to the visit to CERN.

Tonight, she will be judging this year’s Google Science Fair in California at which two Indian American children and two others from Bangalore, in addition to one from Lucknow, are among the 15 finalists chosen from across the globe.

Shree is the youngest of the judges. Others are veterans in one field of science or another from Singapore to the United Kingdom and from Cairo to Chicago. Another winner last year, along with Shree was an Indian American student in the 15-16 age group, Naomi Shah.

The winners were received by President Barack Obama in the White House. Shree recalls with pride that the President asked searching questions about their projects that won them the prestigious prize.

Some months later, Shree met Obama again at another White House event. She was seated in the front row and was surprised when Obama walked up to her, shook her hand and said “Hello, again”.

What would Shree do with the considerable scientific knowledge that she has already accumulated? “I want to communicate science. It is very satisfying to watch people understand things, like I did from my brother,” Shree said.

Her role model is Sanjay Gupta, the CNN medical correspondent who came within a whisker of being appointed US surgeon-general by Obama in 2009, but withdrew his name amid controversy.