At 85, farmer leader Ghulam Mohammad Jaula has found a new and invigorating reason to live and die for. The revival of the “bhaichara” or brotherhood between Jats and Muslims in western Uttar Pradesh, abutting Delhi.

For decades, the unity between Jats and Muslims had dictated electoral politics in the region, where either community made up about 30 per cent of the population.

But the 2013 Muzaffarnagar riots had shredded that bond, fuelling the BJP’s rise to dominance in an area where it never had a foothold, and contributing to the emergence of a nationwide political climate that led the party to victory in the 2014 general election.

But the Narendra Modi government’s imposition of the three farm laws and crackdown on the farmer protests, particularly the one led by Rakesh Tikait at the Ghazipur border, has tentatively brought the two communities together again, promising to heal the wounds of 2013.

“Ab hum unke liye ladenge aur woh hamare liye (Now they will fight for us and we for them),” the six-foot-plus Jaula said, fingers firmly clasped around his stick as he settled in a chair in his outhouse at Jaula village, 40km from district headquarters Muzaffarnagar. “They” meant Jats and “us”, Muslims.

Jaula, who derives his surname from the name of his village, wields considerable authority in the region as former right-hand man of the legendary farmer leader Mahendra Singh “Baba” Tikait, and one-time Muslim face of the Bharatiya Kisan Union.

“Hamara rishta sagey bhaiyon se bhi gehra tha (Our relationship was deeper than that between blood brothers),” is how Jaula describes his bond with the elder Tikait, whose death in 2011 left the BKU in the hands of his sons Naresh and Rakesh.

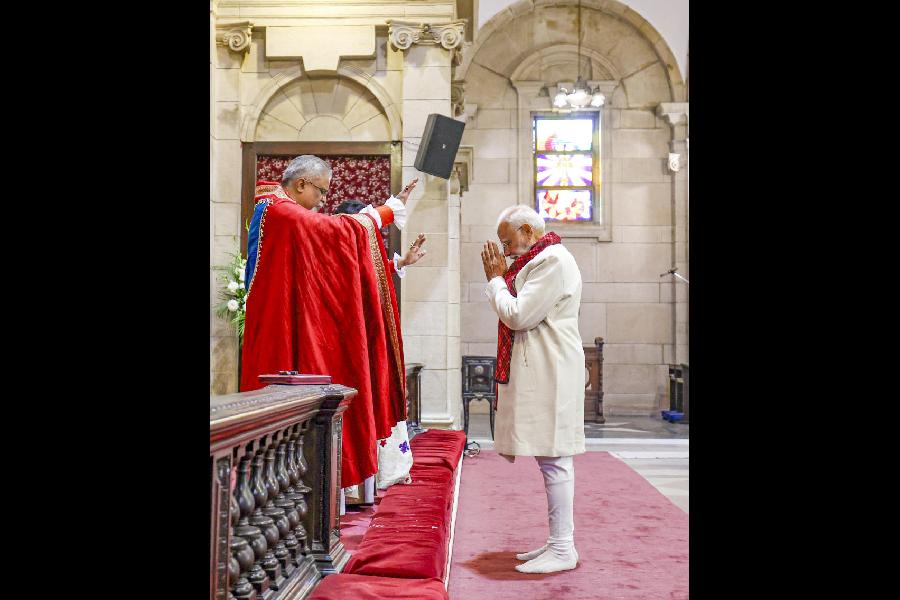

Farmers holding the national flag attend the Kisan Mahapanchayat in Uttar Pradesh’s Shamli district on February 5. PTI photo

Jaula had dissociated himself from the BKU in 2013 after Jats and Muslims found themselves pitted against each other as communal violence engulfed Muzaffarnagar. More than 60 were killed and thousands of Muslim families forced to flee.

With the Tikait brothers accused of involvement in the riots, Jaula snapped ties and floated his own outfit.

Today, the octogenarian doesn’t want to recall the past: the present is too exciting for him. He set off the efforts to bury the hatchet at a January 29 mahapanchayat in Muzaffarnagar, where he told Naresh Tikait to his face to acknowledge the “two mistakes” he and his Jat brethren had committed. Naresh did.

“I told them (Naresh and the Jats) that their first mistake had been to defeat their chaudhary (leader) Ajit Singh (in the 2019 Lok Sabha polls),” Jaula said.

Ajit, Rashtriya Lok Dal leader and son of revered farmer leader and former Prime Minister Charan Singh, had been fielded by a combined Opposition that included the Samajawadi Party and the Bahujan Samaj Party. He lost to the BJP’s Sanjeev Balyan, who stands accused of instigating the 2013 riots.

It was Charan who had in the 1970s united the Jats and Muslims, who stood firmly behind him and Ajit through four decades, with the Samajwadis too benefiting courtesy their off-and-on alliance with Ajit.

The January 29 mahapanchayat had been called after videos from the previous night showed Rakesh Tikait sobbing at the Ghazipur border, accusing the Uttar Pradesh administration and “BJP goons” of conspiring to beat up and kill or evict the protesting farmers.

By the break of dawn, thousands — mainly from western Uttar Pradesh — had arrived at the Ghazipur border in solidarity with the farmers, turning the tide against the government.

However, with their pride and dignity hurt like seldom before, Jat farmer leaders Naresh and Rakesh began looking for political muscle to counter the government and hit on the idea of exhibiting Jat-Muslim unity. Jaula was invited to the afternoon mahapanchayat and he readily agreed.

At the gathering, Jaula reminded the Jats also about their “second mistake”, which actually came six years before the “first mistake”.

“The Muslims had always been with you (the Jats) but you got them killed in 2013,” Jaula told Naresh. A silent crowd, made up mostly of Jat farmers, listened intently.

“These are the two big mistakes you must accept before we move forward,” Jaula said.

Sitting on the stage at the mahapanchayat, Naresh acknowledged the two mistakes and vowed they won’t be repeated again. The crowd cheered.

“When he (Naresh) acknowledged the mistakes, I too brushed aside the past and decided to join the fight,” Jaula said. The following day, Jaula despatched his supporters to the Ghazipur border in more than 200 vehicles in a show of support for Rakesh.

“I’m confident the bond has become stronger and will hold,” Jaula said. “We need each other.”

Since the mahapanchayat, a series of similar farmer gatherings have taken place across western Uttar Pradesh and Haryana, reinforcing the message to the government that the protest wouldn’t be called off until the new farm laws had been repealed.

But the implications of a renewed Jat-Muslim unity in western Uttar Pradesh could go beyond the farmer agitation and have electoral repercussions, with Assembly elections just about a year away.

Jaula is certain that the farmers’ protest itself would influence the outcome of the state polls, particularly if the government fails to repeal the contentious farm laws. “The Jats and the Muslims will vote together in all future elections,” he said.

Jaula’s son Sajid Ali aka Munna Pradhan, a former gram panchayat pradhan, sounded less confident than his father about a complete revival of the old Jat-Muslim ties.

“Yes, a change is visible. Not only the older Jats but their youth too are disappointed in the BJP,” Munna said.

But he added after a pause: “Waise toh sab thik lag raha hai, lekin kaun janta hai unke dil me kya hai (On the face of it everything looks fine but who knows what’s in their heart).”

Recalling the events leading to the Jats’ “first mistake”, Munna said that Ajit, for whom Jaula had campaigned intensely, had looked set to drub Balyan in the 2019 general election.

“However, in a sudden change on polling eve, Jat youths and many of their elders shifted loyalties to the BJP,” Munna said.

Jaula obliquely pointed a finger at the Tikait brothers. “They (the Tikait brothers) called a panchayat and invited Ajit Singh to assure him support,” he said.

“I don’t know what happened (behind the scenes) and the next day, the brothers organised a second panchayat and invited Balyan and promised to support him.”

Balyan belongs to the same “khap” -- the Balyan khap --- as the Tikait brothers. The khap panchayats are traditional village councils that lack official sanctity but wield enormous influence.

It’s widely believed in Muzaffarnagar that the second panchayat called by the Tikait brothers tilted the scales in Balyan’s favour. Ajit lost by just over 3,700 votes.