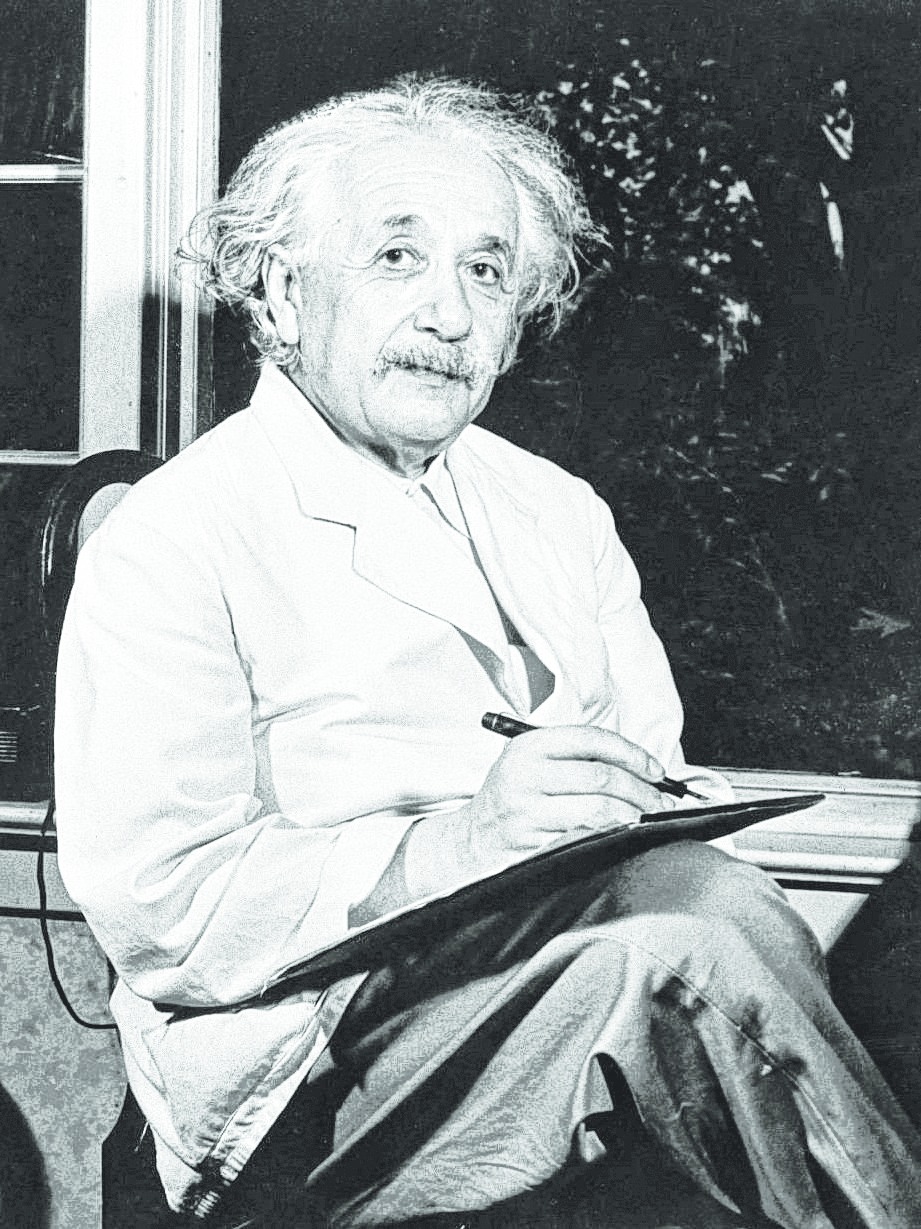

Nov. 24: Abhay Ashtekar is grappling with puzzles that stem from a gift Albert Einstein gave the world and whose centenary falls on Wednesday.

On November 25, 1915, Einstein had set down the equation that radically changed physicists' view of the universe while throwing up challenges that remain unresolved.

Ashtekar, a professor of physics at the Pennsylvania State University, is among physicists worldwide celebrating the centenary of Einstein's general theory of relativity, simultaneously applauding its power and elegance and highlighting its limitations and challenges.

"General relativity changed our view of the universe in ways as never before," Ashtekar said today, speaking over the phone from the US.

"For some 2,000 years, space and time were viewed as the stage of the universe on which everything happens, but general relativity changed that: the stage joined the troupe of actors," said Ashtekar, who is scheduled to visit Berlin next week to speak at a conference titled "A century of general relativity".

The general relativity equations that Einstein had unveiled proposed that mass can distort space and time, like a heavy load pushes down on a spring mattress. Or, to use another analogy, space-time behaves as a jelly-like substance that can stretch and bend under the influence of mass.

"The idea that matter can deform space and time was a revolutionary concept," Hermann Nicolai, director of the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics, Germany, had told this newspaper in an earlier interview on the general relativity centenary.

In 1919, astronomers first confirmed the Sun's effect of bending starlight. Since then, physicists say, the theory of general relativity and several of its predictions have been confirmed through multiple other observations.

"The impact on our understanding of the universe has been profound," said Sumati Surya, a physicist at the Raman Research Institute, Bangalore. "It is because of general relativity that we have moved away from the earlier idea of an infinite, timeless and static universe to one that is finite in time and very dynamical. This is a spectacular example of how science can modify notions that otherwise seem natural from the point of view of philosophy."

Physicists say that general relativity, which demands complex mathematical rigour, has emerged as a key tool in astronomical observations, helps ensure the accuracy of satellite-based positioning, and has inspired some Hollywood movies, including Interstellar (2014).

The theory explains the evolution of the universe: its origin through what physicists call the Big Bang and its expansion. "But the theory also contains the seeds of its own limitations - there are things we cannot understand through general relativity," Nicolai said.

Its equations cannot explain what physicists call singularities - mystery zones for scientists - such as the centres of black holes (or heavy stars that have exhausted their fuel and collapsed into such dense objects that not even light can escape them), or the Big Bang itself.

Physicists believe that attempts to resolve the mystery of singularities would require a unification of general relativity theory with quantum mechanics, another foundational theory of physics that describes the behaviour of the subatomic world.

Ashtekar is among scientists trying to do that through an idea called loop quantum gravity, while physicist Ashoke Sen at the Harish Chandra Institute in Allahabad is pursuing an alternative unification strategy called string theory.

"For the moment, quantum loop gravity and string theory are both competing concepts - they are both attractive in their own ways, but there is little to suggest that one is stronger than the other," said Tarun Souradeep, an astronomer at the Inter University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics, Pune.

Souradeep is a member of a consortium of physicists that wants to establish in India an observatory to look for gravitational waves, the only prediction of general relativity that has not been corroborated experimentally yet.

The consortium has identified three candidate sites in Maharashtra, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh but needs only one to set up the L-shaped gravitational wave detector, each arm of the L stretching 4km but only 150 metres wide.

The US component of a similar highly sensitive gravitational wave detector began scientific runs earlier this year.