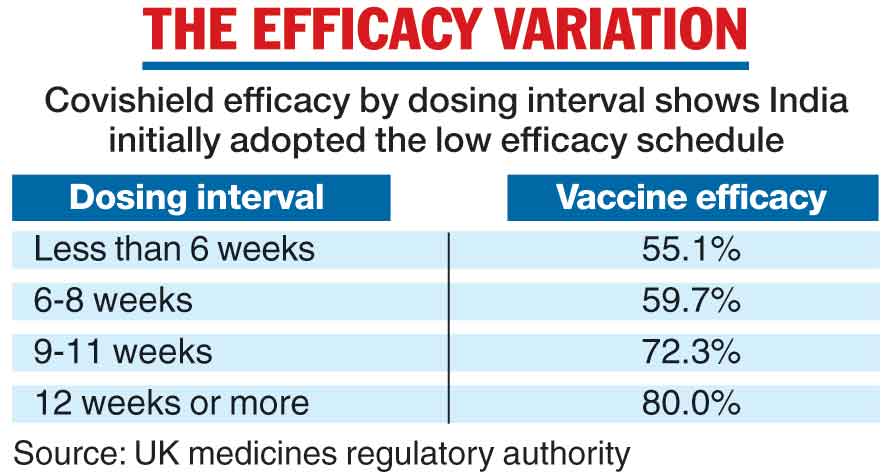

India delayed by more than six weeks a decision to expand the gap between the first and second Covishield vaccine doses to beyond three months although data to support the decision was available in March, medical experts have said.

The delay possibly prevented many people from receiving a dosing schedule that had been found to be far more effective than that initially adopted in India. (See chart)

The Union health ministry said on Thursday that it had accepted a recommendation from two advisory panels on May 12 to expand the dosing interval to 12-16 weeks from the earlier 6-8 weeks recommended by them on March 22.

The ministry said the panels — the National Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (NTAGI) and the National Expert Group on Vaccine Administration for Covid-19 (NEGVAC) — had decided to expand the gap after new “real-world evidence” emerged from the UK.

The gap of 6-8 weeks adopted by India in March — after an initial 4-6 weeks interval — was a deviation from the World Health Organisation’s guidance in February that recommended an interval of 8-12 weeks on the basis of data that showed greater vaccine efficacy with delayed gaps.

“These are pure science-based decisions,” NEGVAC’s chair Vinod Paul, a senior paediatrician and member of the Niti Aayog, India’s apex government think tank, had asserted on Thursday, saying the NTAGI had relied on the “real-life experience” of millions of vaccinated individuals in the UK.

But doctors and vaccine experts say the change in the dosing gap twice in six weeks would have likely contributed to confusion among some vaccine recipients and many may have hurried for second doses amid the current surge of infections.

India’s vaccination campaign has so far administered about 162 million doses of Covishield, which is produced by the Serum Institute of India and accounts for 90 per cent of the total doses injected.

The home-grown Covaxin from Bharat Biotech accounts for the balance 10 per cent.

The data from the UK’s medicines regulatory authority, based on clinical trials with the AstraZeneca vaccine available well before February, showed a 60 per cent vaccine efficacy with the 6-8 weeks dosing interval and an 80 per cent efficacy with a dosing interval of 12 weeks or more. The UK had also adopted the 8-to-12-week gap.

“I think there was little rationale for the 6-to-8-week dosing interval back in March,” an independent vaccination specialist who is not associated with the Indian government or with the two advisory panels told The Telegraph.

“The 12-week dosing interval provides a 20 per cent gain in efficacy and it would have allowed more people to get the first dose of the vaccine between March and now,” said the specialist who requested not to be named. “But it is good India has now increased the interval.”

Questions sent by this newspaper to the NTAGI and the NEGVAC asking about the real-world evidence from the UK that the advisory panels had used to recommend the expanded gap have not elicited responses.

Paul, explaining the latest change on Thursday, had said that when the NTAGI examined the data in March it looked as if “breakthrough infections” (infections after vaccination) would increase. “We cannot afford to increase the risk — the purpose of vaccination is protection,” he said.

He said the NTAGI had examined additional data from the UK’s vaccination experience as part of periodic data reviews. “When we looked at that data and WHO experts were consulted, from the perspective of science, we had confidence to adopt this (latest) change. And there will be no extra risk to people.”

Two vaccine science researchers familiar with developments associated with the AstraZeneca vaccine said they were unaware of any additional data that may have emerged between March 22 and May 12 that could have prompted the NTAGI to change its recommendation.

“They should have done this in March,” one of the researchers said. “It is unclear why they didn’t; only the NTAGI can explain.”

Some doctors speculate that the vaccine shortage may have stirred the rethink. The change will mean more people can get first doses faster at a time when states have offered to vaccinate adults 18 years or older but are struggling to meet the demand.