|

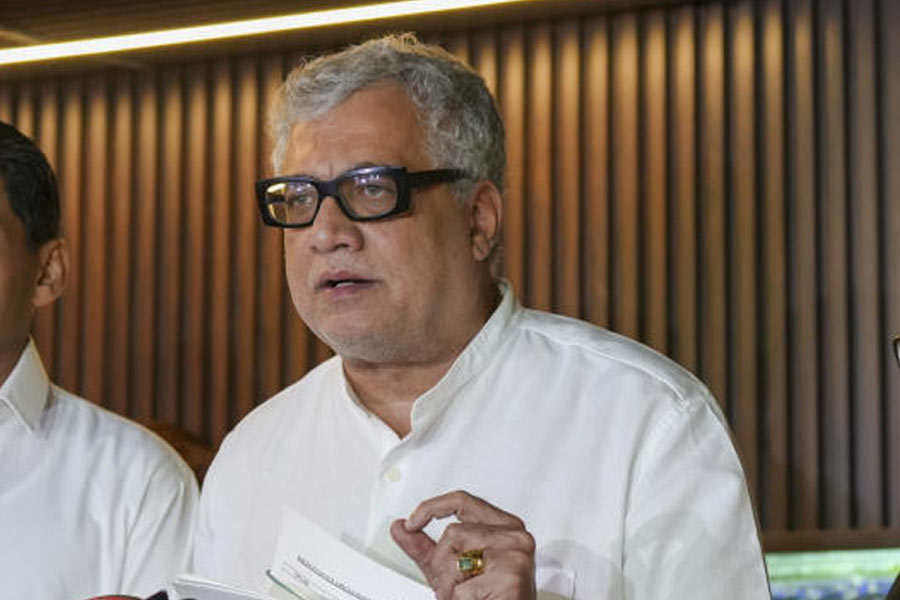

| (Clockwise from top left) Lisadora, Thriem and villagers of Massar. Pictures by Pranab Bora |

Just 35km from Shillong, women of a branch of the Nongsteng clan turn deaf by the time they are 12, an unidentified affliction they have lived with for ages. Some are born deaf. Victims of an unkind system and an uncaring government, they are also often abandoned by their men. In their small community, there are at least 89 of them, old and young.

Massar (Meghalaya)/Guwahati, Dec. 21: “Rkhie, rkhie…” go the people, asking her to smile for the camera and she does, smiling the smile of an angel, tiny halo and all. Lisadora is 6. She can hear her people now, the pleas for a smile perhaps drifting to her like a haze that floats through Massar’s misty winter morning. She doesn’t know it, but it’s so important for her to learn her words, her words for smile, for eat, for sleep, for food, love, day, bathroom, for night… and all else she can put in her tiny mind now. And she must learn them well, to then know them without sound, by the shape of the lips of the speaker, for she is a Nongsteng.

In Massar, in the branch of the clan that Lisadora comes from, the women turn deaf by the age of 12 or so. By that measure, she has just about six years to go before her hearing fades to nothing. When she is grown and wedded, all available indications are that her daughters too could be deaf. Her sons could be too, unless lucky, but they are the exception, the women the rule.

They aren’t born like that and nor was Lisadora. Her teachers at the Sarva Siksha Abhiyan (SSA) school in her village got to know that she was hard of hearing only recently, after she turned five. “She wasn’t responding to sounds the way other kids were,” says Barbilous Nongkynrih, her teacher at the SSA School. “Ours is an inclusive school, we have students who can hear and those who cannot,” he says proudly.

People here do the best they can for their deaf. Recently, Teiborlang Wankhar, the 31-year-old headman of Massar, painstakingly put together the chronological details of the deaf here. Including Lisadora in Massar and 63-year-old Thriem Nongsteng in Pomlum, 9km away, he has traced the Nongstengs’ silent generations over 100 years. The situation is such that to people in the area, the Nongstengs are divided in two, Nongsteng sngew and Nongsteng kyllut, that is Nongstengs who can hear and Nongstengs who can’t, says Wankhar. With the deafness often comes the inability to speak. Wankhar’s list puts the number of deaf and mute at 16.

“Some women, like Thriem, have married out of Massar and now live in villages such as Pomlum and Lyngkyrdem. Their children, too, are deaf,” says Nongkynrih. In all, there are 89 of them, in various stages of deafness, partial to profound. Thriem remembers that her mother and grandmother too were deaf.

Neither the concept, nor the means for early detection of deafness exist here. The only doctor who has ever visited Massar, in keeping with the promise of the district administration, was not an ENT specialist but an eye specialist, who promised she would come back. She hasn’t so far.

Theirs is a home that lies nestled 35km from Shillong, the capital of Meghalaya. The road that twists and turns through the deep mountains from which the Himalayas will eventually rise in the north, leads to the country’s border with Bangladesh at Dawki southward, forking off from the road that leads to the rain-soaked mountains of Cherrapunjee.

Here, among the deep green woods that lie splashed by occasional bursts of wild purple dahlias, live the deaf women of the Nongsteng clan. These aren’t the widows of Brindavan. These are women often abandoned in their homes by the men whose children they have borne. Huddled on the verandah of an old wooden Khasi home, they wait for us, some 15 of them, some profoundly deaf, some partially, vocalising their thoughts through signs and shrill syllables, remnants in their minds of what they managed to learn when they were little Lisadoras themselves. Some, to survive, have learnt to lip-read; some have floundered.

Nongkynrih has had them waiting for us at Massar. Smiling their betel-nut stained smiles, they offer the only explanation they have of their deafness, a legend. A great great granny of whom Lisadora is but the latest progeny, had eaten doh kha syiem, the queen of fishes, and had, as if touched by a curse, turned deaf. Her daughters, and theirs, and theirs, have been that way since, they say. The deaf of Massar are but a small subset among the many that exist in the world with the affliction.

As concentric as they may seem, these circles of silence are as intricate as they are often impossible to penetrate.

The Nongstengs are Khasis, their words and language distinctly their own, yet some words may even be different from the Khasi spoken in Shillong, should there be the slightest variation in culture. The signs they have adopted to communicate hence would be different compared to those in any other valley or plain of silence elsewhere in the world, near or far.

The sign language that Nongkynrih and his teacher colleagues now use with their deaf students thus would have its limitations: “We improvise the best we can to teach them their words and then we have to show them books or draw objects on the black board. We have no proper training which is what we need,” he says.

In her office in Guwahati, some 150 km away in Guwahati in Assam, Brinda Crishna explains what ails the deaf of Massar. “There is urgent need for early detection, care,” she says. “Their deafness seems to be hereditary. To contain it, there must be family planning.” Crishna’s colleagues from Vaani, an NGO that works with deaf children, are some of the very few people who have travelled the narrow mountain road to Massar. “Caring for the deaf is in itself a challenge. It isn’t a readily recognisable cause such HIV. With us funds are difficult to come by,” she says.

There are other problems as well, of supersets, sets and subsets of silence. “The Indian Sign Language (ISL) which we work with is different from American Sign Language (ASL). And remember sign languages are distinct languages with their own grammar,” says Crishna. In Massar, that would mean teaching Nongkynrih and his teacher friends ISL, and then factoring in the words — and their signs — that are unique to the world of Massar. A formal, thorough ISL course would be a beginning for Nongkynrih, but that hasn’t been forthcoming from any quarter, definitely not the state of Meghalaya.

Among the other earnest attempts to cut a path through the silence and connect is the one M.K. Bhuyan and his five-member team make at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) in Guwahati. The team’s Dynamic Hand Gesture Recognition for Human Computer Intelligent Interaction (HCII) project recently won the National Award for Best Applied Research.

Sign language movements by a person wearing a pair of electronic gloves they have developed can be recognised by a computer and turned into audible human words. “The gloves made in the US cost Rs 18 lakh. Ours costs just Rs 40,000,” says Bhuyan, who is an assistant professor at IITG. Once in the market, the gloves could revolutionise communication between those who can’t hear and those who can, even over long distances, in real time, through the Internet.

And will the deaf in Massar be able to afford the gloves one day? “Given the economics involved, they would be more for established schools for the deaf,” says Bhuyan. For Massar, that would mean a school 35km away in Shillong, an institution they have no access to. “Besides, given their handicap, the deaf of Massar don’t like to travel to the world outside,” says Nongkynrih.

Lisadora, meanwhile, is growing, and, going by all available evidence, could have just six years before her world falls silent. In the unrecognised race against time, she hasn’t been taught much at all. For now, though, as faint as she may hear it, she knows rkhie is for ‘smile’.