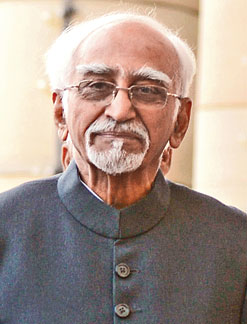

New Delhi, March 28: Vice-President Hamid Ansari will visit Morocco and Senegal next month, ending the complete drought of trips by top Indian leaders to Africa under the Narendra Modi government that has stood out starkly against the administration's claimed outreach to the continent.

Ansari will visit both countries in mid-April in a bid to build on diplomatic gains from the largest India-Africa summit so far last October and reach out to parts of the continent New Delhi has long ignored, three officials familiar with plans for the trip told The Telegraph.

Modi had last October called India's partnership with Africa "natural", their destinies "inter-linked" and had admitted a gap between New Delhi's words and actions with the continent, a concession many African leaders felt was refreshingly honest.

But the Modi government has till now not sent anyone more senior than ministers to Africa since taking over in May 2014. The President, Vice-President and the Prime Minister - the top three dignitaries known as very very important persons (VVIPs) -have not travelled to the continent in this period.

Former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee was the last among the Indian top three to visit Morocco, in 1999. No one more senior than a minister has ever visited Senegal in West Africa from India.

"This is long due, and it would be a great boost for India's diplomacy in the region," said Ruchita Beri, an Africa specialist at the New Delhi-based Institute for Defense Studies and Analyses. "There haven't been many visits to Africa in recent years, and India needs this."

India's trade with Africa stands at $70bn, less than a third of China's trade with the continent, which in 2014-15 amounted to $222bn. More than 95 per cent of India's investments in Africa are in Mauritius, aimed more at rerouting money using that country's taxation laws rather than in manufacturing or services industries.

But the figures have improved over the past decade amid a growing race between India and China for Africa's vast resources and its markets. The continent boasts more than half of the world's fastest growing economies and is viewed by many economists as a future economic engine for the globe.

In North Africa, Casablanca in Morocco has emerged a key hub of Indian investments. Tata Motors has set up a plant manufacturing bus bodies. Ranbaxy has a factory there producing medicines that are exported to the rest of Africa and even Europe. And PepsiCo India has purchased the entire bottling franchise for the drink in that country.

Tata Motors and Ranbaxy also have smaller investments in Senegal. One of the biggest chemical firms in the West African country - the Industries Chimique du Senegal (ICS) - is Indian-owned.

India has also increasingly tried to invest in oil and gas in Africa, in a bid to diversify its sources of hydrocarbons - currently dominated by West Asia. For a small period last year, Nigeria was India's top crude supplier - overall the country is India's second-largest source of oil.

"Partnership between India and Africa is natural because our destinies are so closely inter-linked and our aspirations and challenges are so similar," Modi had said last October while speaking at the end of the India Africa Forum Summit here where all 54 countries in the continent participated for the first time.

At the summit, India and the African Union had agreed to hold the next meet in five years and not in three - as has been the practice with the three editions so far.

The idea behind the decision was to give India and African nations more time to complete projects mapped out at the October summit.

But Indian officials are aware the decision on delaying the next summit is a double-edged sword. The delay is a reflection of a tendency by India in the past to forget about Africa after a summit, and then revive its narrative of bonhomie close to the next meet.

"We are conscious of the shadow that falls between an idea and action, between intention and implementation," Modi had said at the October Africa summit.

A longer gap between two summits increases the risk of India lifting its foot off the pedal on ties, officials said.

Over the past five months since the last summit, the Modi government has consciously tried to suggest that it was keen to keep up the momentum in relations. In January, India had organised a hydrocarbons conference with African nations, attended by several senior ministers. In February, the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (Ficci), with different government arms, held an agribusiness summit with African nations.

But the Vice-President's visit is critical to ending concerns within the African diplomatic community here over the absence of any high-level visit to the continent under the Modi government.

"The idea is to make sure that there is a continuous build-up," Beri said. "It hasn't slowed down."