I have a great love for this country and this city. I am married to a Bengali and I have a home here and I spend a lot of time here,” John Makinson said with a warm smile as we settled down in The Chambers at Taj Bengal on the last day of Tata Steel Kolkata Literary Meet. Over the next 80 minutes, the chairman of Penguin Random House (PRH) worldwide and jamai of Amartya Sen (Makinson is married to Nandana Dev Sen) gave us a peek into the publishing world, the future of books and his pizza test!

Is India an important market for Penguin Random House?

Well, it’s a very important market of the future, because one just has to look at the demographics of India (smiles)! Its importance at the moment in relation to the whole of PRH is not that great in mathematical terms. The reason is book prices in India are very low. But we are very optimistic about the prospects for the book market in India, say in 10 years’ time.

Do you see book prices going up in India in these 10 years?

I expect so. I mean the Indian consumer is very price-sensitive. I always track the price of a hardcover book against the price of a margherita pizza. And if the price of an average-size Domino’s pizza is Rs 550, I think that our books should have at least as much value to a consumer as a few slices of pizza.

Honestly, the price depends on the book. For an important hardcover non-fiction book, for example, I think we should be pricing it nearer to the international norms. Some of those prices have risen. You see now Rs 899 is not an impossible price point for a hardcover book. But for commercial fiction — and this is even truer in vernacular languages in India — it is very difficult to move the price beyond Rs 150-180. Chetan Bhagat kind of sets the standard in pricing in that area.

How should a first-time writer pitch to Penguin Random House?

Well, one of the reasons that writers in India find it a bit difficult to break out is that there isn’t a well-developed literary agent community here. Yes, it is a big problem for authors. Because it’s a very crowded marketplace, there are an awful lot of writers in India. Everybody in Calcutta is a poet, right, everybody? (Laughs) However, one of the things that has been happening more recently is that the self-publishing industry has become a platform for new work. A lot of first-time writers decide to self-publish.

Nandana’s children’s book, Mambi and the Forest Fire, is a Puffin book. And alongside it is a book of her mother’s (Nabaneeta Dev Sen) poetry that Nandana has translated from Bengali, which we have published ourselves. It is a self-published book.

So, I would say to aspiring writers to look at self-publishing. You then have a book out and it is easier to interest a traditional publisher, particularly if the book has attracted an audience.

But aren’t self-published books looked down upon? Reviewers are not keen to review them, an established writer has even called it ‘vanity publishing’…

Well, that’s a slightly old paradigm, I think. The newer paradigm is you use social media to promote self-published works, whether it’s a digital book or a physical one. Of course, book reviews can be important but they are relatively less important than they were and relatively less space is devoted to book reviews in newspapers around the world than was the case 10 years ago. So we have in any case had to think of new ways of drawing the reader’s attention.

There is now a shift from a display model of selling books to what I call a ‘discovery model’ of selling books. So as a publisher you would encourage a bookshop to display your book in the window and create a word of mouth physically. That’s extremely difficult to do online. As first Flipkart and now Amazon are gaining authority in the Indian book market and bookshops find it harder to sustain themselves, we as publishers have to do more to support bookshops, and enable them to promote the works of our authors, particularly the emerging authors....

You often hear that the publishing industry is focused on a smaller and smaller number of titles in which they invest more and more money for marketing. So it’s a sort of winner-take-all market. And then the smaller authors, the mid-list authors, don’t really get much of a looking.

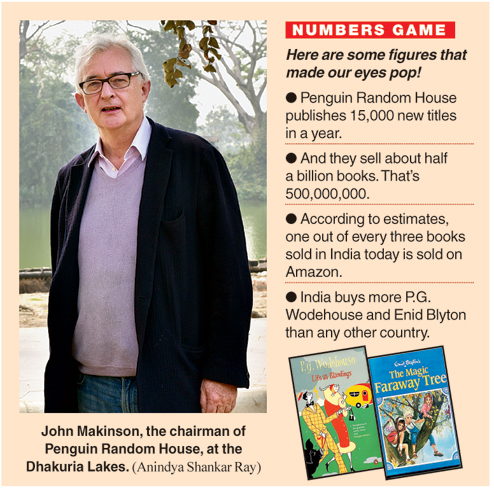

But we have evidence that doesn’t really support that. We are publishing as many books as we have published before. I mean we at PRH publish about 15,000 new titles a year around the world. We sell about half-a-billion books.

In India, in the last year, three publishers have said they are going in for serialised chapters for mobile phones, pay-as-you read formats, etc. Your thoughts?

Well, personally I am rather sceptical about it. There’s been every opportunity in India and everywhere for the reader to say we would like to read in a different way, the way in which the music consumer said, very loudly, ‘We don’t want to buy these albums, we want to buy tracks.’ So if the reader wanted that, by now we would have seen that.

We’ve tried subscription packages, and library ideas and backlist offers for the mobile phone, but on the whole the reader says, ‘No, no, no, I don’t really want that. What I want is this book.’ (Laughs)

He may want it electronically, but there isn’t much evidence in India that consumers are very drawn to very long-form reading on smartphones. The only market where that has taken off in a big way is in South Korea and Japan and to a limited extent in China.

There is a risk that as a publisher I sound like a sort of complacent old dinosaur about this… but e-book sales in India account for about 3 per cent of the total market. In the US, they account for about 35 per cent. Now if the Indian consumer really wanted to read material electronically, the figure would not be 3 per cent.

We mustn’t forget that this is the country that sells more P.G. Wodehouse and Enid Blyton than any other country. The Indian book reader is quite a conservative reader. So, we’ll see... (smiles).

Has there been a revival in interest in physical books in the West recently?

Yes. In the US and the UK, the e-book movement has peaked. In 2015, sales of physical books increased by 8 per cent. Now if we look back five years, if anybody suggested that within five years’ time we would see growth in the physical book market, they would be thought to be mad! I’ve always been more optimistic than most of my colleagues.

Of course, what digital channels make available to people who live outside the metros is the possibility of acquiring the physical book through a direct sales channel in a town where there are no bookshops. Flipkart has got out of the e-book business altogether and given it to Kobo. But physical books can now be made much more widely available.

We as publishers are content people. It doesn’t make any difference to me at all whether we sell content on a printed page or on a screen. It’s actually slightly more profitable to publish it electronically. Then you don’t have returns... our single biggest issue is returns.

What according to you are the three biggest landmarks in publishing?

Well, this goes back to my point about distribution. Consumer attitudes remain fairly constant. What changes dramatically is how we buy books. So, here are my three landmarks...

1. Gutenberg figuring out how to print a book. That was 1439.

2. Second would be Allen Lane founding Penguin in 1935. The reason I think that it is such a landmark is that he completely turned on its head the idea of what kind of content people wanted and how it was distributed. He put machines called ‘Penguincubators’ on railway station platforms so that people could buy a book before they got on a train. He sort of invented the modern paperback and made them accessible.

3. Third would have to be Jeff Bezos establishing Amazon in 1994.

Really, Amazon?!

It has been completely epochal and has been more transformational of the book industry than anything in the last 60 years. He (Bezos) figured out how to distribute books at a very early state electronically... he recognised that books were hugely important sources of consumer data — if someone buys a book about lawnmowers he might be interested in buying a lawnmower as well!

He developed an interest in every aspect of the book economy. So Amazon is by miles the biggest retailer of books in the world, also the biggest retailer of second-hand books, through Amazon Marketplace it is the biggest consumer platform in books, it is the biggest deliverer of audio content in the world, it is far and away the world’s largest self-publishing company, it sells computer systems that support book activities, it is everywhere! It’s difficult to get data but we reckon that one out of every three books sold today in India is sold on Amazon.

Publishers get spooked by Amazon because it is so successful and grows so fast and it is so, so threatening and disruptive. But it is also doing a lot to help the distribution of books, by pricing books aggressively, by opening up new channels for books, by investing not just in the e-book format but in the Kindle. It has actually done a lot around the world to promote reading. And also the idea of the single-copy purchase.

What is single-copy purchase?

It means that when you go to acquire a book, you are buying one whole book. You aren’t subscribing to Spotify and being able to download all the music in the world onto your mobile device. It is technologically possible to do that in books, there isn’t any reason why there can’t be a gigantic subscription service but the consumer doesn’t seem to be interested and Amazon doesn’t particularly encourage that.

On a personal note, what do you like to read?

Oh, I read all sorts of stuff. I’ve been reading a wonderful volume of short stories called Swimmer Among the Stars, by Kanishk Tharoor. I’ve just finished off the first volume of Niall Ferguson’s extraordinary biography of Henry Kissinger (Kissinger 1923-1968: The Idealist).

Is there something that we’ve not asked you that you wish to talk about?

Regional languages! We are going to do more of that. In Bengali we will probably talk with Ananda Publishers about how we might publish in that language. We’re thinking about how we can do more in Hindi, we’re thinking about Telugu, about Tamil.... The challenge is there aren’t enough literary translators. In China we have worked with the government and British Council etc, to promote seminars about literary translations. I talked to Jawhar Sircar (CEO of Prasar Bharati) about translations from Bengali. But government has to play a role in that.

Samhita Chakraborty

Would you rather buy a book for Rs 500 or a pizza? Tell t2@abp.in