|

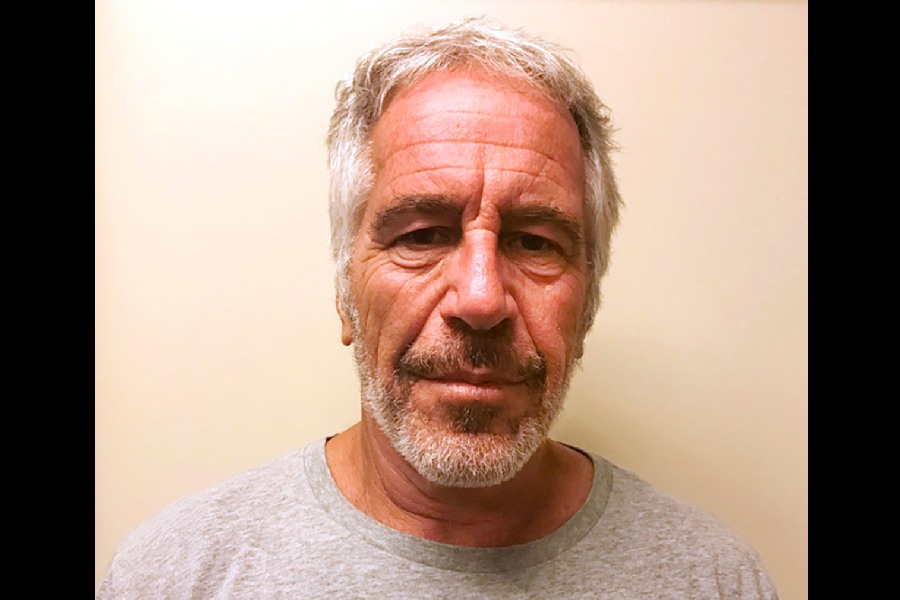

| Miti Adhikari at the Maida Vale Studios in London |

THE JOURNEY

Tell us about your Calcutta connection....

I grew up in south Calcutta at our family home in Hindustan Park. The building is now a fire station. My father, artist Jhupu Adhikari, worked in advertising. Most of my schooling was in a boarding school in Darjeeling called Mount Hermon School, which had a very good musical tradition and that’s where I had an early introduction to the creation and performance of music. A couple of other scallywags and me formed a band in school and our reward was the attention of girls.

My father was posted in Bangalore for a few years and there I had my first guitar lessons with the legendary Gussy Rikh. Bangalore also had a very vibrant band scene at the time and I was fascinated by the whole aura surrounding the bands of that era.

You also had a band here in Calcutta…

Yes, we called ourselves Mahamaya and it was formed by Sanjay Mishra, now a classical guitarist in the US; Shyamal Maitra, tabalchi and percussionist du jour in Paris; Kim Hagen, a New Zealander on the run from Interpol with whereabouts unknown, and me. In those days and until recently, you had to play covers of the great bands of the time... the Beatles, Rolling Stones, Grateful Dead. I played bass and did some lead vocals. We played lots of shows in Kala Mandir, Vidya Mandir and the clubs in Calcutta. We even played a huge outdoor show in a stadium in Bangalore with various bands from Bombay and Madras. We felt like real rockstars because the organisers had paid for our travel and hotels and paid us a fee... couldn’t have been more than a couple of thousand rupees then.

When did you leave Calcutta and why?

I left Calcutta and India in 1977. There was no future in being a musician in India unless you worked in the film business. I did not want to end up in advertising, which many of my contemporaries did. So it was suggested by my mother, who is English, that I go to London and visit the English side of my family.

Also, Mark Tully, the BBC correspondent who was a family friend, thought I would stand a good chance of getting into the BBC as a trainee studio manager. That is the BBC term for a studio engineer. London was in the throes of the punk explosion and although I, a Calcutta Deadhead, didn’t get it and found it repulsive, it soon became clear to me that music comes from the social and economic cauldron of the time. Once I became immersed in the Britain of the late ’70s, the scales fell off my eyes and I started listening to bands like The Clash, Graham Parker and Elvis Costello, and my Grateful Dead cassettes started gathering dust on the top shelf.

I never really wanted to be a sound engineer, but as a musician I was intensely curious to learn about the process of recording. There is very little training. You have to learn by experimenting and then learning from your mistakes. So I applied to the BBC for a job as a studio manager and after six months of interviews and form filling, I was accepted.

INTO THE HALL OF MAIDA VALE FAME

How did you land a job at the legendary Maida Vale Studios?

Part of the training process involved visiting the various studio complexes that the BBC had. One of these was the Maida Vale Studios. I spent a couple of days there, sitting in on sessions with the Only Ones and The Damned. It was also the home of the Radiophonics Workshop, a warren of rooms with amazing synthesisers and other devices where people were paid to be creative. I knew right there and then that Maida Vale was where I wanted to work. So I pestered my boss incessantly until he finally relented and allowed me to try out as an assistant.

And now you’ve spent more than three decades there…

If someone had told me back in 1977 that I would spend my entire working life in music and never sit at an office desk, I would have suspected that they were on drugs. But yes, it’s been 34 years and I have resigned now from the BBC, planning to spend more time on my outside projects. I’m producing an album for a very young London band called Famy. We are recording it in a church with a mobile studio parked outside. It is a hugely challenging and exciting project and quite different from my work for the BBC.

Being in the thick of so much musical action with musical greats, wasn’t it tough staying behind the scenes?

I do miss performing and playing but working in a studio leaves you with little time to follow your musical dreams. Now that I will have more time, I plan to get my guitar playing up to scratch

|

‘What happens in the studio, stays in the studio’

You’ve worked with some of the best in the West. Who have been your favourite artistes?

Although I’ve worked with some very famous bands, I will always remember working with them when they were completely unknown. Blur, Coldplay and Radiohead were just youngsters when they came to Maida Vale for the first time. They were hungrier and more open to creative input then. We used to go to the pub round the corner after the session and our friendship still endures. In fact, my leaving party is at the very same pub and I expect one or two will show up.

And the worst?

What happens in the studio, stays in the studio.

Big artistes often come with big egos. How have you dealt with that?

Egos are actually a form of insecurity. Once you understand that, it’s easy to deal with someone who might seem difficult outwardly but is in fact crying out for reassurance.

What would you say is your greatest memory from the studio floors?

There are many, many great memories but a recent session with Pearl Jam stands out. They kept their private jet waiting because I wanted Eddie Vedder to do some vocal overdubs. He gave me his own monogrammed Zippo lighter as a ‘thank you’.

Nirvana to Pink Floyd

Your association with Nirvana dates back to Kurt Cobain and carries on with Dave Grohl’s Foo Fighters.

Take us through your journey with them…

The Nirvana association was tragically very short. I mixed their seminal performance at the Reading Festival in 1992. Kurt was a very sweet but also very quiet guy. He was very focused on the recording we were doing but still had time for a joke or two. When we had finished recording all the parts, Dave, Kris and I went to the pub for some beers and food. Kurt stayed behind and when we got back after an hour or so we found him fast asleep on the couch. It is fitting that my last mix for the BBC will be the Foo Fighters at Reading this year.

Pink Floyd have been known for being the pioneers of live music and you were a part of their Live 8 concert series.

Tell us about that stint.

I did the live broadcast mix of their performance. I was introduced to Roger Waters and Dave Gilmour and that was it really. But that will have to be one of the highlights of my career — mixing their one and only reunion gig live for the whole world.

MY COUSIN NEEL

Bollywood music is big in India and Bengali film music is also picking up fast. Does that interest you?

I know very little about it but from what I know, it doesn’t hold much attraction for me. Their aesthetics will have to change quite radically for me to get involved. Having said that, I have done a bit of work with Agnee (a Pune-based rock band who scored the music for Manish Tiwary’s Dil Dosti Etc.), which I quite enjoyed.

What then drew your attention back to India a few years ago?

It was five years ago actually when I started writing, producing and mixing with my cousin Neel Adhikari on various fusion tracks. It was through him that I came across The Supersonics and we produced that together. I realised that the Indian music scene was about to explode. I very much wanted to be a part of it.

Who are the other Indian artistes, apart from The Supersonics and Ska Vengers, that you worked with?

I produced the Menwhopause album Easy, mixed the Jackrabbit album and recently I’ve mixed some tracks on Tritha Sinha’s forthcoming album. I’ve also been involved with the soundtrack for Q’s new film Tasher Desh which has a galaxy of collaborators — Susheela Raman, ADF, Sam Mills, Neel Adhikari, Anusheh.

Anything that you feel the Indian recording industry still lacks?

I was going to say good studios but I think there are enough. Everything can be done in small-scale facilities these days because of the domination of computers. I also think that India lacks the technical skills that top-class engineers bring to the table. There are many reasons for the lack of technical expertise in the Indian recording industry but the main one is the absence of tradition. I learnt from the best engineers in the business and they learnt from the best before them. After 50 years of this, you have a tradition. India will acquire that eventually in the future.

Is there any Indian artiste you wish to record or produce for?

I’d really like to work with Peter Cat Recording Co (PCRC) but they haven’t been persuaded yet. You can play PCRCs music to a roomful of people and half of them will love it, the other half will start vomiting. To me that is the sign of good music. I also would like the opportunity to work with the Shakey Rays from Chennai. I just like the little I have heard of them.

How do you keep up with the new sounds and technology changes?

I am lucky to know and work with the best engineers in the world. You can pick up a lot over a couple of pints in the pub.

You were also involved with the musical side of the Olympics this year in London...

It just happened over this weekend (June 23 and 24). Jay-Z and Rihanna, Kasabian and Jack White were some of the artistes involved. It was a two-day festival which is part of the cultural Olympiad. Hackney Weekend where it all happened is a music festival run by BBC Radio 1, who held their annual free music festival at Hackney Marshes East London in the run-up to the 2012 Olympics. My job was to do the broadcast mix on the main stage.

Return to roots

How often do you visit Calcutta? What do you do when you are here?

I visit Calcutta at least once a year. It is my hometown and no one can understand the meaning of the word unless they have been away for a while. My walk changes, my voice changes, and my mind loosens up.

You’ve said in one of your interviews that you’d like to return to Calcutta. How serious are you about it? Have you set a date?

I expect to move to Calcutta in the autumn of next year. I want to return to Cal because it is my hometown and I’d like to spend more time with my family and my friends. Work-wise, I’d like to establish and expand the production company called MANA (Miti Adhikari and Neel Adhikari) that I have with Neel. My wife Sam, who is a major figure in festival production in the UK, is interested in looking into the possibilities for artiste management and event production in India.

And till then?

As I said earlier, I will be working on the Famy album for the next few months then hopefully The Supersonics second album will be the next thing. We are setting the groundwork for it at the moment.

You live in London with: My wife Sam.

Biggest influence: My dad (Jhupu Adhikari).

Favourite band: Radiohead.

Favourite solo artiste: Bob Dylan.

Favourite Indian music artistes: Peter Cat Recording Co, The Supersonics, Shakey Rays.

Artiste you regret not having worked with yet: Bob Dylan.

What you miss most about not living in Calcutta: Phuchka and jhaal muri.

One change that you’d wish for in Calcutta: That the lovely old buildings are preserved and restored.

Fave Indian song: Horihor from Gandu

Fave Indian film: Gandu.

Fave Indian actor: Anubrata Basu from Gandu.

Mohua Das

Did you know about Miti before reading this interview? Tell t2@abp.in