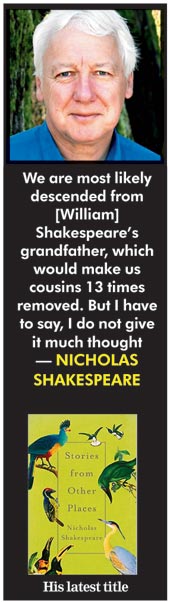

We were intrigued by his famous surname enough to reach out to Nicholas Shakespeare, who lives in the UK. And in the process we discovered a new writer we can’t wait to read! There’s a hitch, though. None of the bookstores we dialled had his books. Dear inventory keepers, are you listening?

Nicholas Shakespeare debuted as a novelist in 1989 with The Vision of Elena Silves, which won the Somerset Maugham Award. In 1993, Granta magazine listed him among 20 best of young British novelists. Ahead of his Mumbai visit a couple of months back for Tata Literature Live!, the 59-year-old answered a few questions from t2 over email.

You must be getting a lot of attention because of your forefather? How exactly are you related to William Shakespeare?

Shakespeare’s last direct relative with his name, Elizabeth Shakespeare, died in 1670. After World War II, my great-uncle Geoffrey Shakespeare commissioned the Royal College of Arms to compile a family tree. It turned out we are the only family called Shakespeare who can trace their origins back to the 16th century. The College decided that we are most likely descended from Shakespeare’s grandfather, which would make us cousins 13 times removed. But I have to say, I do not give it much thought; I’m not on royalties. It gets more commented on abroad — in the UK, you usually have to spell the name out. WS himself spelled it several different ways, though perhaps not as many as the number of claimants who are supposed to have written his plays — 112 at the last count.

What or who was your inspiration to become a writer?

The first writer I knew was my grandfather (S.P.B. Mais), and he was the reason why I never wanted to become a writer myself. The author of more than 300 books, he died in his 90th year, bankrupt and heartbroken shortly after my grandmother — his companion of half a century — ran off with a man who first proposed to her when she was 17. His story has continued to haunt me. I still catch myself saying: if that’s what happens to writers, count me out.

The second writer I met was Jorge Luis Borges (the Argentine writer-poet) and he was the reason I wanted to become a writer. When I was 16 my family lived in Buenos Aires, and I used to read to Borges in his small dark flat on Avenida Maipu, as a lot of visitors did. He had only to open his mouth to say something that made an impression.

“You must never look for beauty. You must let beauty come to you. Those who look for beauty are mere journalists.”

If a reader wants to start reading you, which book would you recommend they start with?

Perhaps Stories from Other Places, my latest. These stories written over 30 years are set in India (where my father was born), and in countries where I have lived, including France, Argentina, Australia, Tasmania, France, Canada and Africa.

From Peru to Tasmania, your books traverse a diverse landscape! How do you pick your stories?

For me, it tends to be a pebble-in-the-shoe thing. A situation or dilemma suddenly presents itself that I can’t resolve unless by writing about it. The novel takes the shape of the answer. For instance, my first novel, The Vision of Elena Silves, started with a walk through the Portuguese city of Coimbra. I was pointed out the convent where the last surviving witness of the Miracle of Fatima still lived (in which the Virgin Mary had appeared to three peasant children and warned them of the dangers of communism). It was the end of the university term and students were celebrating in the streets below the convent. I had this powerful image of an old lady at the end of her life, in her cell, listening to young men and women outside, laughing, drinking, about to make love — and wondering: has it been worth the candle to have been locked away as a young girl by the church since 1916? Would it have been better not to know that God exists, to have fallen in love and made a different life in the world?

And so I made her 40 years younger, and I had her escape the convent to find the man she had been in love with, and I set the novel in Peru at the time of the Shining Path insurgency in the 1980s.

What is the best thing you learnt from the life of Bruce Chatwin while writing his biography?

I learned that he did not make things up, as some of his critics said; and that he told not so much a truth as a truth and a half. He was in a sense strangely incapable of invention. His talent was to connect what was already there. He was a precursor of the Internet, a connective super highway without boundaries, and with instant access to different cultures. He was a storyteller of bracing prose, at once glass-clear and dense, who offered a brand new way of representing travelling. And he held out in his six books the possibility of something wonderful and unifying, inundating us with information but also with the promise that we will one day get to the root of it.

As his friend Robyn Davidson said: “He posed questions that we all want answered and perhaps gave the illusion that they were answerable.”

Samhita Chakraborty