Oscar-nominated filmmaker Ashvin Kumar believes India is still not prepared to send films to the Academy Awards and come back winning because of the tendency to hail mediocrity.

Ashvin, whose film Little Terrorist (2004) was nominated for best live action short category at the 2005 Oscars, feels it is the regional films that has the capability to make the cut at the world podium, as Hindi cinema hasn't changed for good over the years.

After socio-political documentaries: Inshallah Football (2010) and Inshallah, Kashmir (2012) were first banned, then acclaimed, and then went on to win National Awards in 2011 and 2012, Ashvin now knows nothing comes easy in this industry.

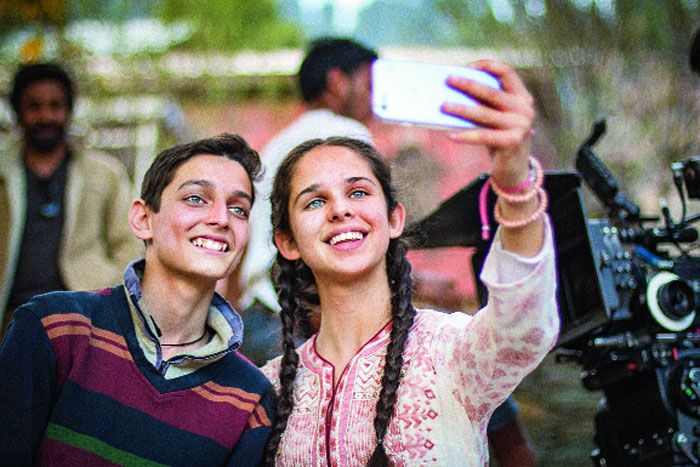

His recent narrative on the Valley - No Fathers in Kashmir (2019) - too found resistance at the censor board initially but he feels it has now got resonance as it is “the film of its time” as India goes through upheavals in the North.

Son of reputable fashion designer Ritu Kumar, this Calcutta-born director chats with The Telegraph on where he draws lines between good, wrong and very wrong.

Children have been central characters in all your films. Was it intentional?

I find it helpful and useful to delve into the personal lives of people affected by conflict, be it at a border, in a fraught-war-like state like Kashmir, or in the corridors of a boarding school through the eyes of teens and kids because they somehow are very beautifully balanced (and) poised on that cusp of going from innocence to awareness. And a lot of the films I have made actually catch them at that particular moment in their transformation, where a particular inciting incident leads them to literally grow up in front of our eyes in the duration of the movie. It is very much the case in Little Terrorist (2004), Dazed in Doon (2010), Inshallah Football (2009), though it is a documentary it literally see the main character Sharat grow up in front of the lens as he goes through these experiences. And it's very much the case in No Fathers in Kashmir (2019) and this helps us enter a world with innocence. It creates deep empathy for a pure and pristine vision of the world, the way it could or should have been or can be. And then it goes about as a character in the film like Noor in No Fathers in Kashmir start discovering things about her past and the disappearance of her father. The dark horrors and realities of what is real tries to seep in. My aim is always to emotionally engage the audience and keep them in a suspenseful state during the film and it helps the audience to participate from a teenager's point of view as they get to understand what the world is all about. It also helps you navigate deeply complicated, complex, fraught and divisive issues like Kashmir or the relationship between India and Pakistan from the point of view of innocence and idealism, which is not accessible in their 20s or after because by then cynicism or worldly knowledge have already seeped in and conflict then becomes a matter of partisanship and polarities and taking sides if not entirely propagandist. What teenagers help me do in the films that I have made to express conflict, is try and shed those preoccupations with which we are conditioned to view Kashmir. It helps us take a completely different view on the conflict which is almost like a clean slate. That is why I work with children and yes it is certainly intentional.

You write your own films. Why is that? Do you avoid conflicts in creativity?

(A long laugh) No. I have never thought about that because I think creativity is all about conflict. Without challenge I think creative people will become not very creative. The reason I write my films is because, I suppose, I have a particular way of looking at the world and wanting to represent it in a particular way. And so I just found it almost reflexive to be a writer first and then become a director. That's not to say how I began because I started in theatre which of course you know you are not writing your stuff. You always perform stuff written by others. At least the kind of theatre I used to do, but still today I am open to work on other people's screenplays, but I have never been offered a screenplay to direct and I'll be very interested to do so and even commission other writers to write scripts for me. I find the process to be fascinating. Like I will be very happy to collaborate and ring-fence myself to the work of directing.

An Oscar nomination for your second film. Were you elated or satisfied that the world has seen what you wanted to convey?

I was firstly very surprised actually. I knew I had made a reasonably good film, but for it to travel and strike a chord in the hearts of people so far away from the experience of the film - like America, Los Angeles and travelled to over 250 festivals - was different. In fact even today, 15 years after it (Little Terrorist) was made, it is far more relevant than it was in the time it was made. Which is actually another point all together. But I don't think one is ever satisfied because had the film had the impact I wanted it to have, maybe we would have been discussing the issue that it threw up in a very different way in India today. Story of a Muslim boy who crosses the border by mistake and adopted by a Brahmin family who takes him back. This theme is particularly poignant and relevant in our day-to-day life. That very community the boy belongs to has been disenfranchised in many ways and with the recent legislation that the Indian government is trying to bring in, exactly that refugee boy who came from across the border would not be welcome in our country and would be asked to leave just because he is a Muslim, is deeply problematic and adds so much resonance today than it ever had. The problem has deepened much further today than it was at the time of making Little Terrorist. So am I satisfied? No I am deeply dissatisfied because films like Little Terrorist and other sane voices are murdered in our political discourse and in the end we have bipolar, muscular nationalism which defines a community, which is very much part of our nation as “other”, which is very saddening. Now whether I was elated, of course I was elated because it's an indescribable experience and to be recognised so early on in one's career for the fact that you managed to put a movie together pretty much on a rubber-band budget and facilities that were hardly existing and myself not knowing too much at that time to be just going on with gut feeling, instinct and sheer confidence. It was a career-turning experience. Had it not for the Oscar nomination I would have thought of something else with my career. I would have been doing something else. But it gave me confidence that maybe there's something here that I should explore.

How much do you think Indian cinema has changed over the years?

Many things have changed but many more have remained entirely static. When you say Indian cinema I assume the question doesn't restrict to Hindi cinema and opens its ambit to all cinema like Bengali, Malayalam, Kannada, Tamil and cinemas of the regions such as Northeast and Punjab. A lot of things are happening in Malayalam cinema, in Tamil cinema. Malayalam cinema for sure and Bengali cinema has been extremely strong with stories and reality. Malayalam cinema has been very strong with real stories becoming box-office successes as well. And then we have cinema coming out from the regions, particularly Assam, the Northeast, from the heartland. Sadly what has not changed is our Hindi cinema. Which tends to take the maximum amount of footage in terms of media spin and spend. The distribution systems continue to be very hostile towards independent films. Experimentation is not particularly encouraged. And the rise of Internet platforms has only broadened out the mediocre. A lot more work has been generated, a lot of actors who were struggling now have work. But I don't think there's any rise in the quality of things. That sadly remains quite static. A lot more stuff is coming out but a lot mediocrity as well. A lot of emphasis is placed on those who have already achieved something, and there is absolutely very little encouragement for people who are doing something different. For example people like me. We find ourselves on the margin of this operation whereas we have audiences for our output. But this industry is not geared to look at niches but continues to look at blockbuster opening weekends. Till that changes Hindi cinema is not going anywhere. It is very encouraging to see that regional cinemas don't really care much about Hindi cinema. Marathi cinema again has shown that we can create films in the vernacular language and have good box-office outings as well as critical acclaim. Yes, regional cinema has become more democratic, whereas Hindi cinema has become more mediocre. It's in the regions that we see flashes of excellence. And excellence is what we should all strive towards.

When it comes to the Oscars, Indian cinema is yet to crack the code. Where do we lack?

I think I have answered this question when I talked about excellence. Basically, we lack in creating an infrastructure that nurtures real, diverse, independent, original eccentric voices. Our infrastructure is totally geared towards making superstars out of the actors and directors rather than making superstars out of that unsung hero despite creating something mesmerising and gem like. The incubation process of films, the encouragement from industry and government, the celebration of a filmmaker as an author as an artiste, all these contribute to create world-class cinemas that could go to places like the Oscars. But none of these things are in evidence in our country. Filmmakers make films despite the industry and not because of it. And this is the biggest tragedy here.

Do you think Indian cinema stands anywhere near Iran, Israel, US, Korea or France?

No, it doesn't. Exactly why I had mentioned before. Our cinema is particularly in a certain sense, we filmmakers are not encouraged to find an authentic voice. Filmmakers here are encouraged to find larger audiences. And these two things are sometimes not compatible. If a filmmaker finds an original voice, audience will gravitate around that voice and it will become a new way of looking at something. Take the examples of Tim Burton, Abbas Kiarostami. These are the kind of filmmakers who have found an original voice and then audiences have found them. Because they want to see an original voice. (Quentin) Tarantino again comes to mind. We don't inculcate that. Our system is very much set up against that.

Where does Indian cinema stand in terms of world movies?

We are a continent of stories. Our stories are so deep and so profound. I am actually travelling right now and making a documentary from Thiruvananthapuram and ending in Calcutta, and my basic quest is to experience my world, my country, my culture on a one-on-one basis. And wherever I'm going I find stores in every nook and cranny. We are blessed with a huge variety and diversity of conflicts of human crises and human achievements. Evidences of human condition. We don't have any dearth of stories. Our main issue is we are unable to strive for a certain excellence within them to be able to bring it to the world in poignant ways. I think sadly our movies don't really appeal the way say an Iranian film would. What has attracted the world to us is the box-office turnover. And in a smaller way almost an orientalist look back into India like we make movies on people shaking their head and dancing. These are the things that signify Indian films. And there's almost a humorous side. Very few of our films are actually taken seriously in a sort of significant way other that the few which manages to win a few awards in the recent past where there have been a certain resurgence of films going to Cannes, and various other festivals and winning some awards. But the point is these films face a very hostile box office and a very hostile environment when they come back and release in this country.

Kashmir has been your favourite premise. Any particular reason?

I won't call it a favourite premise. I think Kashmir represents national trauma. And a moment where Indian democracy has failed miserably, particularly illustrated after August 5, where all pretences were left out at the door and the solemnly, sacredly, constitutionally guaranteed, compact made was basically repealed rendering an autonomous state, which at the time of its accession to India, was given its own status, own flag, own constitution and even its own Prime Minister and under which conditions it was given to India, was just repealed and thrown away. I saw 10 years ago the calamity and tragedy of what happens when the high-handedness of the State is allowed to proceed without any checks or balance and I decided to make movies about this. Because I was in the mistaken belief that this was an aberration and a few films and a few articles written here and there would highlight the injustice that was being done in the name of the republic of India and in my name as a citizen of that republic. Unfortunately that faith was belied and today the most nightmarish situation is being allowed to play out - where that injustice instead of being livened by decades that followed has been deepened into converting the entire state of Jammu and Kashmir into an Indian colony, which is being manned by our armed forces and there is absolutely no legal mandate for that to have happened. I regret to say that the selection of Kashmir as a place to investigate and engage with compassion and empathy with the people of our democracy who had been sidelined and marginalised, only in a dark way have been vindicated.

Your mother is a reputable designer and you a filmmaker. Any particular reason why you chose filmmaking?

(Long pause) I am always at a loss of words when I am asked questions like this. Well, my mother being a designer has nothing to really do with my choice of being a filmmaker other than the fact that there has been freedom and encouragement coming from both my parents that have allowed me to pursue a career that I wanted to pursue rather than them insisting me to take up something that they had selected. Being first-generation entrepreneurs, who are pretty much self-made people coming from very simple backgrounds themselves, they have created whatever they have out of sheer talent and hard work that they put up. I was encouraged to take up lessons from them. And filmmaking came up to me because I was actively part of theatre as an actor on the school stage first and then after a short period in Delhi and then after that deciding to switchover to making films. Perhaps the freedom they gave me for that exploration to take place. And the fact they have created their own space and own mark on the world they wanted me to do the same in some sense. But yes if not a filmmaker I would have been an architect or perhaps a fashion designer.

Which film of 2019 according to you should have been India's official entry to the Oscars?

I would not like to answer that because there's a conflict of interest or maybe not but I am not qualified to answer this.

What is your next project?

I am working as an actor in a film called Sandhya, which is being directed by a first-time woman filmmaker. I will be doing that in the middle of this year and it's set in Pune. At the moment I am filming a travel documentary which I spoke about. I am also going to start writing a period film set in the 18th century, which I hope to mount next year or so.