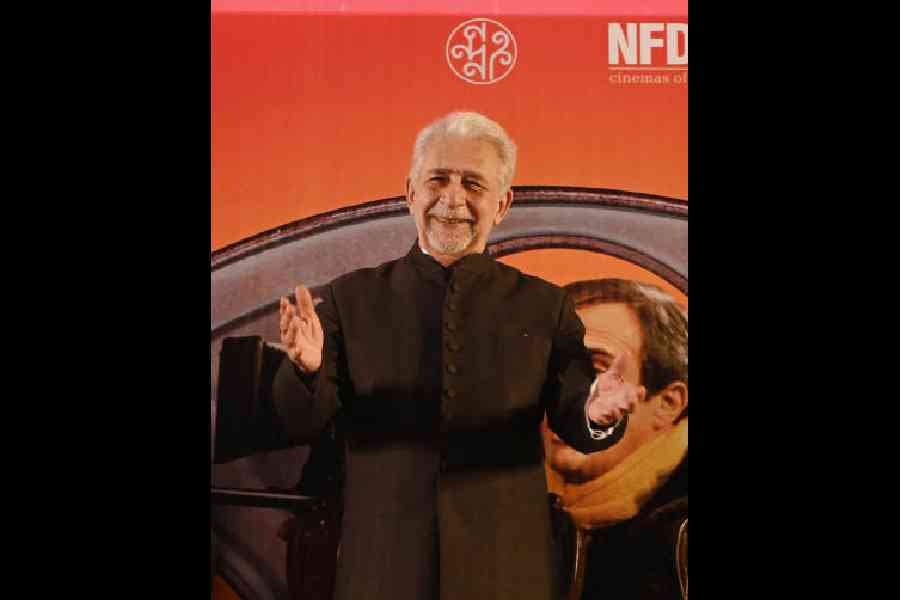

Naseeruddin Shah arrived in Nandan, the venue of the ongoing French Film Festival, for the post-screening interaction with the audience, about seven minutes late. “I was watching the (India-Pakistan cricket) match. I am a cricket fanatic,” he confessed on walking into the elevator with t2.

It was a full house that had just finished watching his Manthan, Alliance Francaise du Bengale director Nicolas Facino mentioned as he welcomed him. They got to watch the 4K restored version that was showcased last year at the Salle Bunuel in Cannes. And the spectators had stayed back, each one of them, to listen to the man who had played Bhola, a Harijan community leader who initially mistrusts the higher caste panchayat head of the village but in the end continues the work of the milk cooperative initiated by Dr Rao, a well-meaning and visionary veterinarian.

Shah did not sit and watch Manthan with them that day. But the reason he gave at the start of his speech was not what common sense predicted — that he had already watched it more than once. “It brings back too many memories of old friends and associates who are no more — Girish (Karnad), Smita (Patil), Amrish (Puri), most recently Shyam (Benegal) himself,” he said. Here’s what Shah shared with the audience on the film.

“Manthan was my second film after Nishant. Nishant was also by Shyam Benegal and was very successful. After Nishant, everyone else got work except me. I got good reviews. That’s all. I started wondering what was wrong with me. Then Shyam told me one day that he was making another film. He was carrying a file on which was written GCMMF. That seemed to be from a Don Martin comic. The full form turned out to be Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation. It was producing the film. Five lakh farmers had contributed ₹2 each. ₹10 lakh in 1976 was enough to make a film with so many characters on location. Today that would be the cost of a single day’s shoot!

The reception

We all had faith in Shyam, most of all me. But most people said: “Who would see a film on milkmen? It would be like a documentary.” But it turned out to be Shyam’s most successful film if you calculate the ratio of the film’s cost to the money it made.

The film is based on an experience of Dr Verghese Kurien, who started this milk cooperative movement. There were a few cooperatives, most notably at Anand in Gujarat, which was their headquarter. But the village where we shot it did not have one at that time.

Manthan received a lukewarm response in the first week and people said: “See, we told you!” The second week I saw it in the theatre and I was astonished at the reaction. People lapped it up! There was applause in certain places and laughter too, as there is a bit of humour in the film. It ran for six or seven weeks at the same theatre.

After Manthan, I started getting work as people realised I was the same nincompoop who had acted in Nishant, as if I had drunk a magic elixir of Asterix. I was at that time fresh out of the film institute and believed in the narrative method. I revered actors like Mr (Marlon) Brando or Robert De Nero. I was also deeply influenced by the films of France, Germany, Sweden...

I am not particularly fond of Hindi film songs. I have always felt very foolish if I have to do a song. When I am asked to name the most difficult thing I had to do as an actor, I say it is singing romantic songs with girls half my age!

The making

I told Shyam that I wanted to go on location a week in advance to study the villagers and I’d live in the hut which would be shown as my home in the film. Shyam agreed. It was a village of Bharwads, a tribe of shepherds and cattle keepers — graceful, elegant people. The way they use their lathi is amazing. It becomes a part of their body.

I put on the clothes and the turban they wear, took my bedding and went to spend the night in the hut. It did not last long. Soon I spied a beautiful black scorpion. That cured me of my method-acting madness.

Too much is made of it (method acting). An actor spends six months in a wheelchair to play a wheelchair-bound role. None of this is becoming a character. It is all practice. The actor is simply doing what needs to be done to portray the character well. After that, I started doing everything else I needed to do for the role other than sleeping in the hut. I learnt how to milk my cattle, wash them and feed them. I became friends with a buffalo who also appears in the film.

Actors who forget they are playing a part and become too involved are the ones who get into all sorts of trouble. Their sanity gets endangered. I don’t buy that. If you become the character then you are of no use to anybody.

There were wonderful actors and friends on the sets — Amrish, Mohan Agashe, Smita... Girish was not a friend but a teacher. He was then the director of the film institute (Film and Television Institute of India). I really enjoyed myself.

The best part of the film was that the farmers shared in the profits. Cooperatives sprang up all across the country after the film was shown in villages. I held a screening in a little village of milk farmers in Mussoorie. It was fascinating to watch them respond to the film.

The afterthought

Shyam decided to include a song after the film was made. Vanraj Bhatia then composed a theme for the title. Shyam told me later that Vanraj wasn’t getting what he wanted. He told him: “I need a voice. Just instruments will not work.” Preeti Sagar, a wonderful singer who used to sing jingles for ads, was called. While the discussion was going on between Shyam and Vanraj, Preeti’s 12-year-old sister (Niti), who was sitting there, scribbled down something in Gujarati and showed to Shyam. Her lines became the song Preeti gave voice to, which binds the film. She had initially sung it in a dainty voice. Shyam goaded her to coarsen her voice so that it would sound like a rustic girl’s. There is a saying that a film gets made on the editing table. It is completely true of Manthan.

Many people said Manthan was like a documentary. The film gave a boost to documentary filmmakers.

Postscript

If you think of it, cinema is the only medium which can actually record its times. It is a combination of all arts and captures life exactly as it is.

I don’t know whether cinema can change the world or alter a person’s mindset. But it can encourage the mindset to move in the same direction. Ironically, that’s what is happening in our country right now. You see movies that are skewed in their perception of certain communities and they are catering to those who subscribe to those beliefs.

In the same way, cinema can also have a positive effect on society; at least that’s what I hope. Even if it can’t, I do consider it my responsibility to participate in such films.

It’s not that I don’t like entertaining films. Of course, I do. I too wanted to be a star when I was 19 or 20 years old. I did not choose art films. Art films chose me. It was a coincidence. While doing these movies over the years, I have realised why I am devoted to these films. Some of those were not very good but I have no regrets.