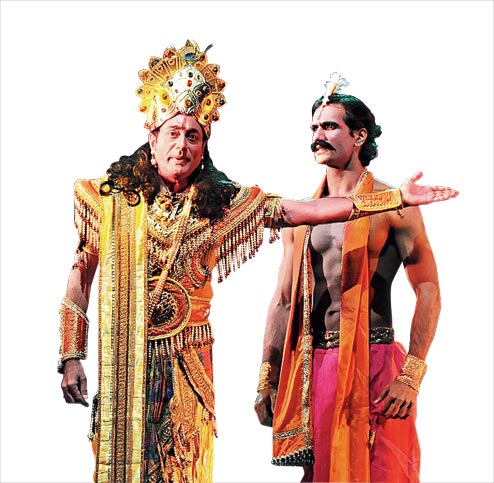

The second day of Mahabharata Retold saw the 13th day of the great war of Kurukshetra being played out on stage, in Atul Satya Kaushik’s play Chakravyuh. It is the story of that fateful day when the young warrior, Abhimanyu, dies fighting the Kauravas alone, having been trapped in their chakravyuh (a strategic war formation).

Amid lots of wartime action, fights with sticks and malla yuddh (combat wrestling), the play shows how Arjun’s son Abhimanyu falls prey to the combined strength of the scheming Kaurava army in the absence of his father and how he puts up a brave fight till his last breath.

The fights are so real you start worrying that someone might get hurt on stage. But soon you realise that the play is more than about a battle, it’s also a treatise on the philosophy of chakravyuh — a trap of karma as well as dharma and how we all are somehow struggling to come out of our personal chakravyuhs in life.

This exposition happens through Krishna, another important character in the play. As the news of Abhimanyu’s death spreads, Krishna gets bombarded with questions from Abhimanyu’s near and dear ones about the justification of a young warrior’s killing at the hands of the enemies, in the absence of any support from the Pandavas.

At this, Krishna points out the fallacies in their reasoning and explains the many whys that cloud their minds.

Through Krishna’s speech, in Devnagari poetic verse, the play addresses various issues of life, some of which are as relevant in today’s world as they had been in the times of the Mahabharata. No wonder, each message drew a loud applause.

On parent-child relationships

• Yadi pratyek pita yogya putra ko uchit dharohar de deta, to aaj is ranabhumi par yeh mahasamar hi na hota (if every father would have properly empowered the son who was able, then today this great battle wouldn’t have happened in the first place).

On single motherhood

• Jin putro ne Ayodhya ko sammohit kar dala tha, aise Luv Kush ko Sita ne bin pita ke hi to pala tha (those two boys who had mesmerised the kingdom of Ayodhya, Luv and Kush, were raised alone by their mother).

• Aane wale yugon mein aise nirnay lengi mataye, ki swayam apni ichchha se ekaki balak palengi mataye (in future, women will decide to raise their children all by themselves).

On taking vows

• Priya bahat hai shapath pratigya is kul ke har vangshaj ko, jise dekho shapat baddh hai, anuj ho ya chahe agraj ho; Mano shapath hai ek swami, manav to matro ek sevak hai, karya kathin karne ko kya shapath hi ekmatra prerark hai (taking vows seems to be a favourite practice among the royal family members here. Whether senior or junior, it is as if the vow is the master and the men mere slaves. Is the vow the sole inspiration to perform tough tasks)?

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Who is Draupadi? A character from the Mahabharata or someone around us, living among us? Well, if we go by Atul Satya Kaushik’s stage production of the same name, then it could be anyone. Just like the women in the village where the play is set. Using a red dupatta for prop, the rustic women take turns to play Draupadi, tell her story and in turn their own story as well.

Draupadi is the story of a village and its women, and men. One day, the men of the village leave for a wedding ceremony, and the women decide to spend the night together. At one point, they start enacting scenes from a play that some of them used to stage about a decade ago. This play, also called Draupadi, has a past. It had been banned by the patriarchs of the village for allegedly spoiling the minds of women. Now that there is no man, it is their chance to relive the play’s empowering moments.

Thus begins Draupadi, as different women play out different parts of the character’s life from the Mahabharata. But what seems to have happened ages ago suddenly becomes relatable in the lives of these women. If Draupadi had been wronged time and again by the patriarchs of Hastinapur, then so are these women, each in her own way, by the male-dominated society.

Atul Satya Kaushik has aptly used folk music performed live on stage by the cast and a supporting crew to give this play-within-a-play the much-needed vibrancy.

Issues such as forced marriage, rape, the Partition and its scars, the futility of war, and the importance of a woman standing up for her rights came up all through the play.

.jpg)

I loved the play. The story is based on the Mahabharata, but we could relate our lives to it. Women still have a long way to go, only we can solve our problems. There is no Krishna or anyone else. We have to stand up for ourselves.

— Sudarshana Bandyopadhyay

It was a very interesting experience... with the actors bringing women power into the play in their own way. Himani (Shivpuri) is a very good actor and a good friend of mine. Besides her, the girl who was singing most of the songs (Latika Jain) was very good. I liked the group’s power.

— Usha Ganguli, theatre director and actor

The play was brilliant and few parts gave me goosebumps. The saying that behind every successful man is a woman is wrong. It should be beside every successful man, there’s a woman. I really enjoyed the play. — Pallak Malhotra

The play showed how Draupadi’s life is relatable to the lives of today’s women, the problems that she faced and how we are facing it today. It’s not just a story of the past but also of the present. The play is wonderful... the acting and the songs.

— Labanya Ray

Text: Sibendu Das. Pictures: Chanchal Ghosh